by

Sarah Hawk

Introduction

by

The Celts were a warrior race which occupied a large part of Europe from at least the 7th century BC until the German invasions of the 5th century AD, and their traditions still predominate in many parts of Europe today.

Because the Celts did not become literate until after they'd been converted to Christianity, in reconstructing their lives we've had to rely on accounts of other ancient peoples, particularly the Greeks and the Romans, both of whom were almost overwhelmed by invading Celts in the 4th and 3rd centuries BC, and both of whom later conquered and enslaved thousands of Celts; on their myths, which were recorded by Christian monks centuries after the Celtic heyday; and on archaeological evidence which, fortunately, is abundant.

What emerges from these varied sources is a picture of the Celts as a people with rich and dynamic lives, art, and institutions built around a warrior ethic and an heroic ideal.

And part of that ideal involved both nudity in battle and monogamous homosexual relationships between warriors.

First the Greeks and then the Romans described both Celtic warrior nudity and Celtic warrior homosexuality. For a time these descriptions, particularly of nudity in battle, were discounted as the sort of dismissive detail the Mediterranean peoples used to denigrate their northern barbarian foes.

But over time, archaeological evidence has bolstered the claims of writers like Polybius, Diodorus Siculus, Caesar, and Strabo, and today it's generally accepted that the Celts often did fight nude, even against the heavily armored Greeks and Romans.

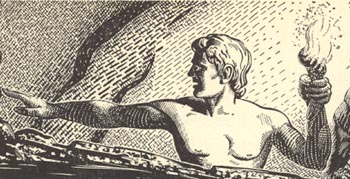

For example, as Stephen Allen remarks in Osprey's Celtic Warrior

Greeks and Romans were disconcerted to be faced with large numbers of Celtic warriors who fought completely naked. Yet the custom was not new and had been practiced by the Greeks themselves in earlier times.

This reality of nude combat among so many warrior peoples, like the reality of nudity in Greek athletics and of nudity in Greco-Roman combat sports, including wrestling, boxing, and pancration, is one which is difficult for us to understand today.

Not only does our culture have a strong prohibition against public nudity, but it's next to impossible for us to imagine exposing our genitals to the dangers of combat, or even of athletic competition.

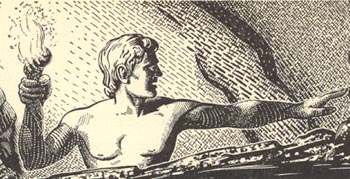

|

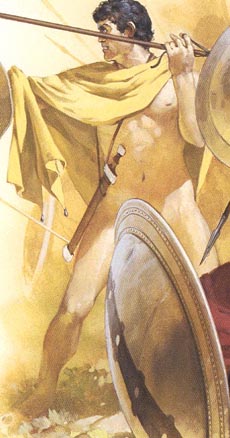

this Osprey artist's reconstruction is based upon a vase painting |

Yet clearly, men have, in times past, felt a strong and indeed overwhelming need to appear naked before their male foes.

Despite the obvious danger.

We know, for example, from written accounts by the Greeks, that in early hoplite warfare lower abdominal and genital injuries were among the most common, and among the most deadly.

Here, for example, are two accounts by the Spartan poet Tyrtaios, who lived ca 650 BC, of hoplite warfare and its aftermath:

Let him fight toe to toe and shield against shield hard driven,

crest against crest and helmet on helmet, chest against chest;

Let him close hard and fight it out with his opposite foeman,

holding tight to the hilt of his sword, or his long spear.At the very forefront an older man falls and lies down in front of the younger,

his hair white and his beard grey,

breathing out his last strong spirit amidst the dust,

holding in his hands his testicles all bloody.

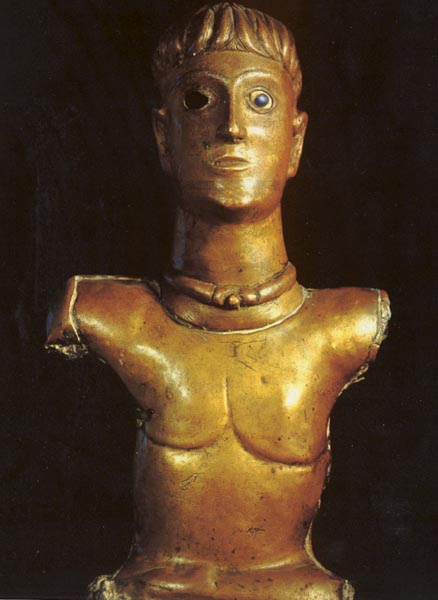

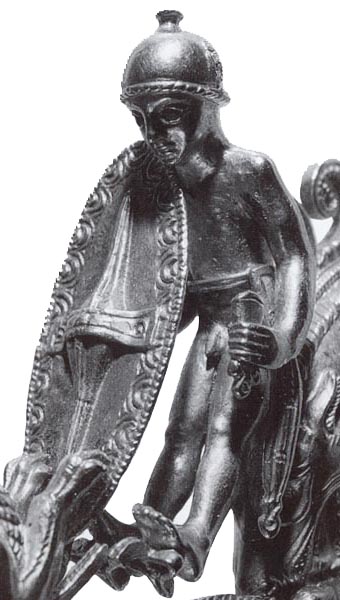

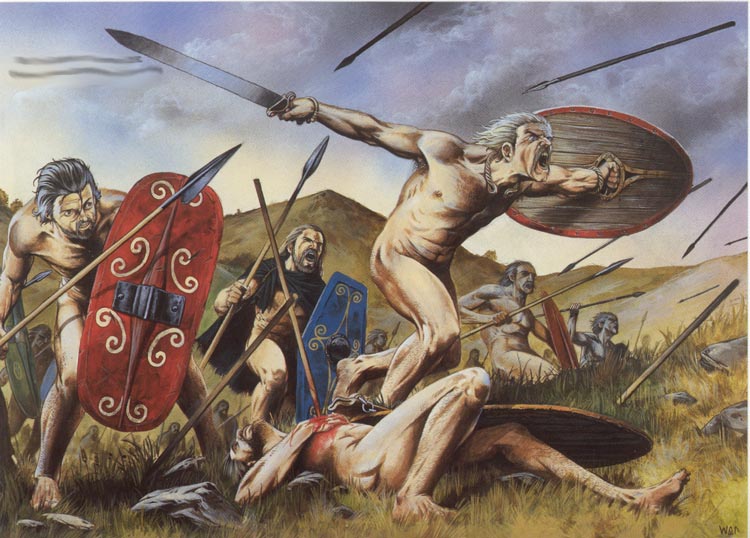

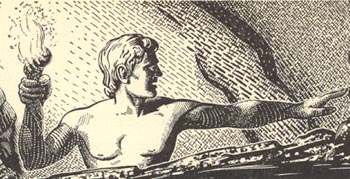

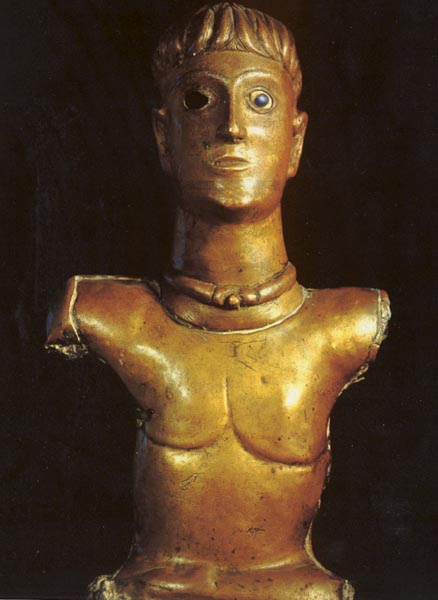

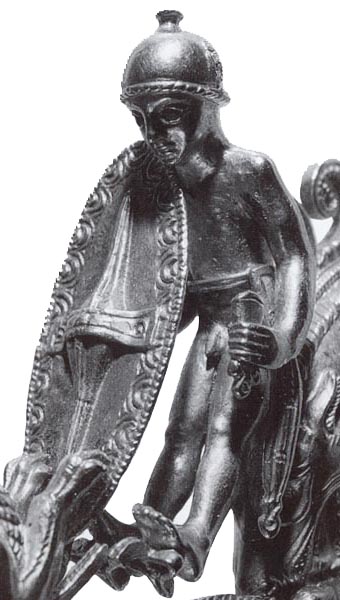

As dangerous as this practice was for the Greeks, who generally carried a large round shield and some body armor, it was far more dangerous for the Celts, who often were completely nude, as we can see in this bronze of a Celtic warrior found in Italy:

Ancient writers say that this sort of nudity in battle was paticularly common among the Celtic Gaesatae, freelance fighters who banded together to seek their fortune, and who shared a very high esprit de corps.

These Gaesatae, according to Allen,

...formed distinct groups outside the traditional social structure of the tribe or clan. ... The warrior would have dedicated himself to his fellow Gaesatae [as did the Spartans to their mess mates and lovers and Boeotian warriors to their fellows and lovers in the Sacred Band of Thebes] and very likely to a god of war, for example Camulos in Britain and Gaul. Thus, nudity on the battlefield assumed ritual significance. Protected and empowered by divine forces, the warrior displayed his strength and had no need for either armour or clothing.

|

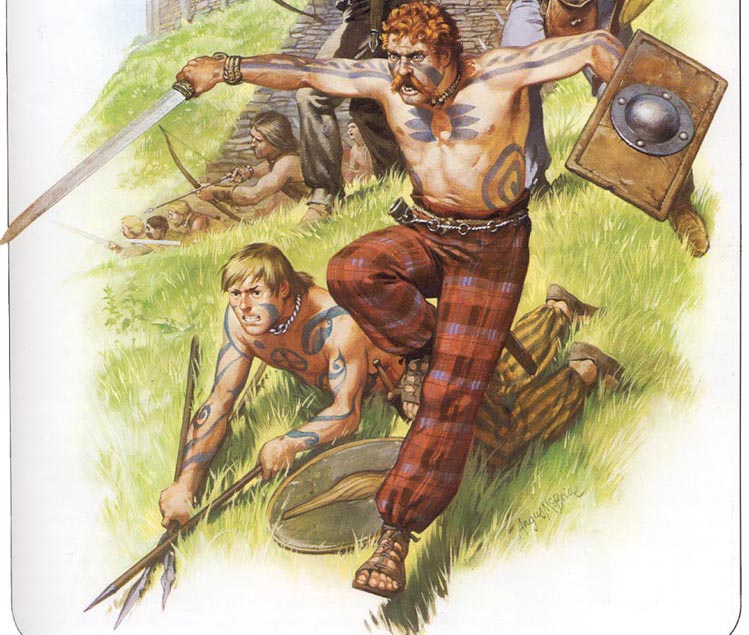

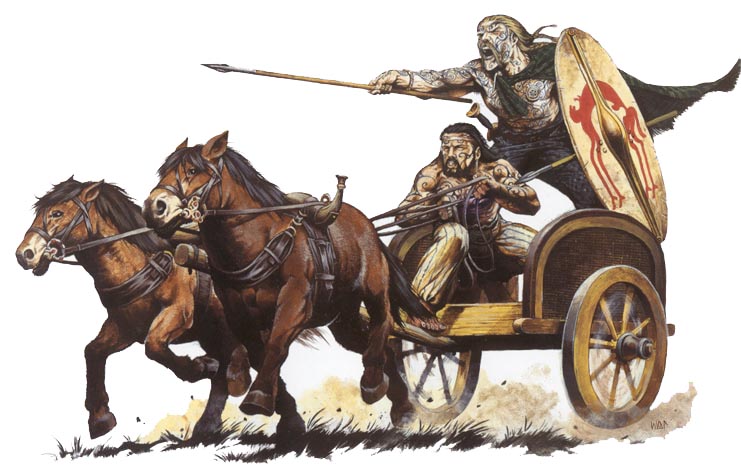

the carynx is on the right |

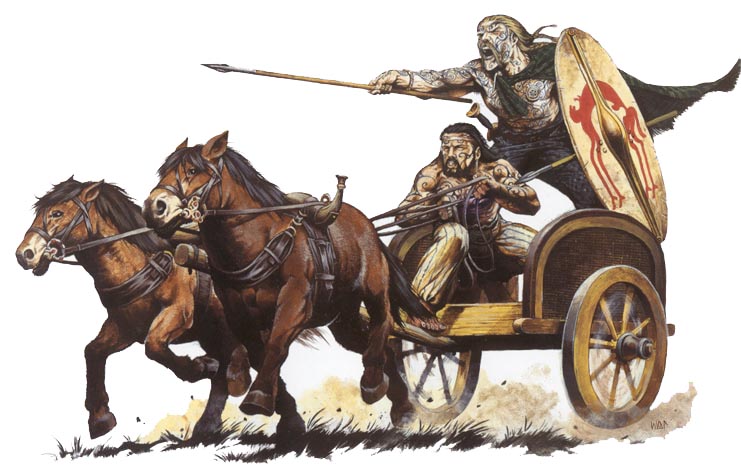

There were other battle rituals.

Having first deployed into tribal and clan contingents, the Celts began by assaulting their enemies with an awesome and terrifying noise produced through banging their weapons on their shields, singing war chants, yelling, and sounding a long horn called a carynx, which is described as braying and strident.

The carynx not only rattled the nerves of their opponents, but also, it's believed, summoned aid from otherworldly forces immanent in the earth itself, adding further to the warrior's sense of being under divine protection.

Then leading warriors would step forward to challenge opponents to single armed combat.

Whether the champion representing his tribe triumphed or died, the effect of these duels was to raise to an even greater pitch the warrior's fury and ferocity, and at the climactic moment the opposing warriors launched themselves into frenzied and furious attack.

The great Celtic epic, the Tain, describes its mythic hero's battle frenzy in the following phallic terms:

Then the frenzy of battle came upon him. You would have thought that every hair was being driven into his head, that every hair was tipped with a spark of fire. He opened one eye until it was no wider than the eye of a needle; he opened the other until it was a big as a wooden bowl. He bared his teeth from jaw to ear and opened his mouth until the gullet could be seen. A swelling and an inflation filled the warrior from top to ground, as the wind fills a spread, open banner, and he became deep purple and red all over. ... The hero's light rose from his forehead. As high, as thick, as strong, as powerful, and as long as the mast of a great ship was the straight stream of dark blood which rose up from the very top of his head and dissoved into a dark magical mist.

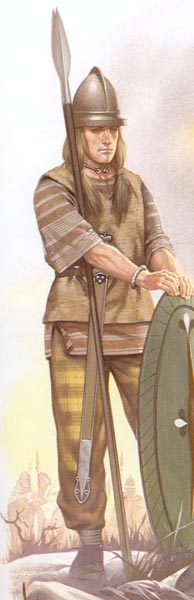

It was in such a fury and believing himself protected by mystical powers that the Celt launched his charge upon the enemy, first throwing his javelins at close range, then using his shield to batter his way into the enemy's ranks, thrusting with his spear or slashing with his sword.

Against other Celts, all convinced that death was preferable to dishonor, glory more important than length of days, and that an eternal warrior's existence of hunting, feasting, drinking, and fighting awaited them in the afterlife, these tactics quickly led to a series of bloody individual combats, with acclaim for the victor and a worthy death for his foe.

But against the discplined ranks of the Greeks and especially the heavily armored Romans, who maintained a shield wall and would not be drawn into duels, the result was not happy for the Celts:

And while the Romans, like the Greeks before them, admired the fighting spirit and love of liberty of their Celtic foes, they were able to first defeat them, and ultimately, to conquer them:

It's important to be clear about why the Romans triumphed.

Because ancient writers described the Celts as tall, muscular, and very pale of skin, white supremacists, from the 19th century on, have tried to make of the Celts some sort of super-race.

They were not. The Celts were just people, passionate, proud, and bold, but people after all, and that's why Rome was able to defeat and conquer them.

Not that the Romans were genetically superior either, but because the Romans had built, in military terms, a more effective machine, a machine which was a product of their culture and of certain ideas about war they'd acquired from the Macedonians and the Greeks.

In that respect, the Celts were no different from other peoples, such as the Zulus or Aztecs, who came up against the superiority of what Victor Davis Hanson calls "the western way of war."

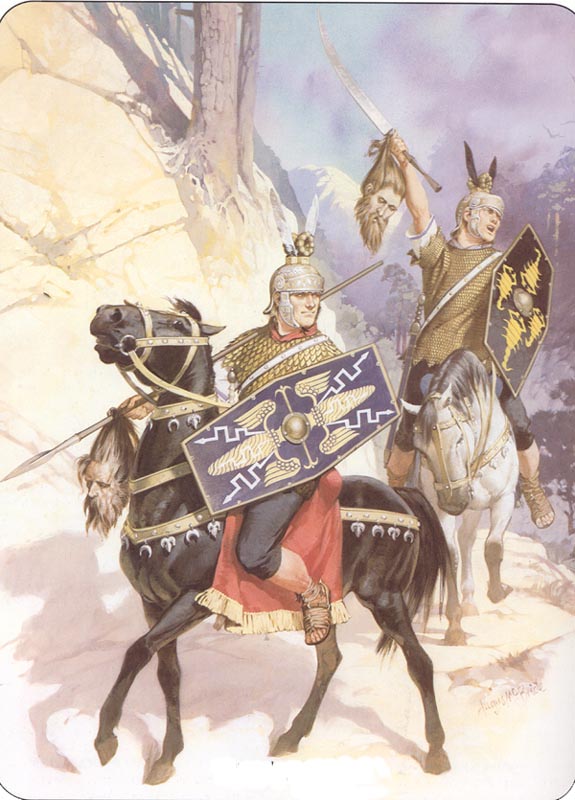

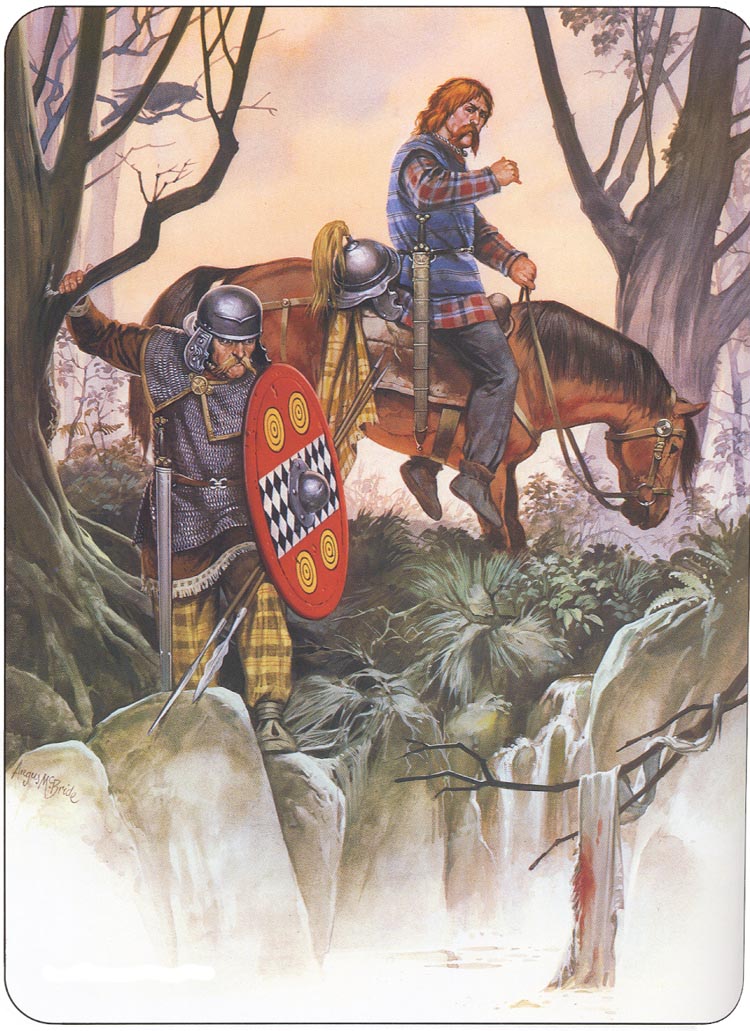

Like those other peoples, Celts were capable, if they chose and over time, of learning other ways of making war, and that's why, in Romanized Britain and Gaul, there were many Celtic legionaries, shown in this Osprey artist's conception in Roman uniform but carrying, as a Celt would, the severed heads of their enemies:

Of course not all of the Celts succumbed to Rome. Those in Ireland and in the north of Britain remained free and continued to attack the Romans, regularly testing the strength of Hadrian's wall:

And still practicing ritual and heroic nudity in battle.

|

What does all this have to do with us, men into fightin' and frot?

A lot.

From childhood on, many of us have had fantasies about nude combat.

Yet there was nothing in our culture which would have suggested that such a thing had ever or would ever take place.

It's not as though our Oylmpic athletes wrestled nude, or that our history books routinely referred to warrior nudity in battle.

Yet many of us knew -- "instinctively," or perhaps as part of what the Swiss psychologist Jung called racial memory -- that such nudity was possible, natural, and right.

And I believe that were it possible to obtain complete information about the history of every people, research would show that some form of warrior nudity is part of their heritage.

Many of us too have been told that we are odd because we wanted to wrestle or fight nude, and to rub cocks too.

Yet such has been the experience of generations of warriors, and such is therefore part of the universal heritage of men.

As has been and is the exclusive love of one man for another.

In the last decade military historians have finally begun to acknowledge warrior homosexuality.

For example, Peter Wilcox remarks that

From early puberty the young man of the warrior caste progressed through the martial arts of the Celt, with the accompaniment of hunting, feasting, and drinking. As a fully-fledged warrior he would support and be supported in battle by a close age group of his own peers, who had been with him throughout his training for manhood. In this way many young men developed a strong man-to-man bond; and Diodorus, Strabo, and Athenaeus all remark that homo-erotic practices were common among the Celts.

Of course what Wilcox describes was equally true of the Spartans, Thebans, Athenians, and all other Greeks, and again I have no doubt that such has been a universal of the warrior experience.

In the essay which appears below, Celtic scholar Sarah Hawk adds to our picture of the Celts, these proud, handsome, and fiercely heroic nude warriors, by describing the love affair between their mythic hero and Hercules figure Cuchulainn (pronounced "Ku Kullen") and his 'heart's companion' Ferdiad.

It's a beautifully told tale, and like similar stories among the Greeks, it helped model man-man love for generations of young Celts.

And can do the same for us today.

Because just as nude combat is part of the universal heritage of men, so is the heroic love of one man for another.

That heritage has been too long suppressed.

Through our Alliance, it is being reborn.

January 5, 2004

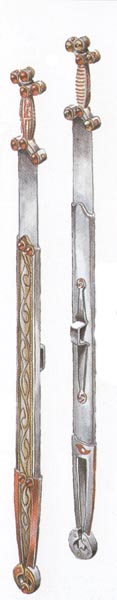

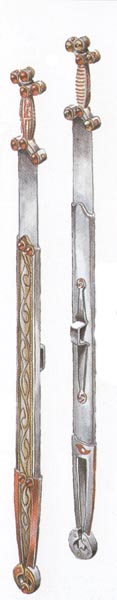

Celtic Warrior Torcs

worn by warriors

who fought nude

and loved one another

by

Sarah Hawk

The information that we have about the Celts is scanty, most of it from myth. However, travelers and philosophers at the time commented that the Celts frequently carried on male/male relationships, intimate on both a physical and a spiritual level. It was remarked that Celts often slept on animal skins with their male lovers. Their relationships were varied -- intergenerational, often military in nature; gender-variant; and egalitarian. This suggests that no set 'ideal' of a man/man love relationship existed.

While marriage was a sacred and valued institution, their society was, most likely, one in which men were free to express their love and desire for one another in relative freedom. Evidence also exists that close pair-bonds were often formed between men, bonds of brotherhood that occasionally verged into something . . . other. Something for which there is regrettably no modern-day analogy.

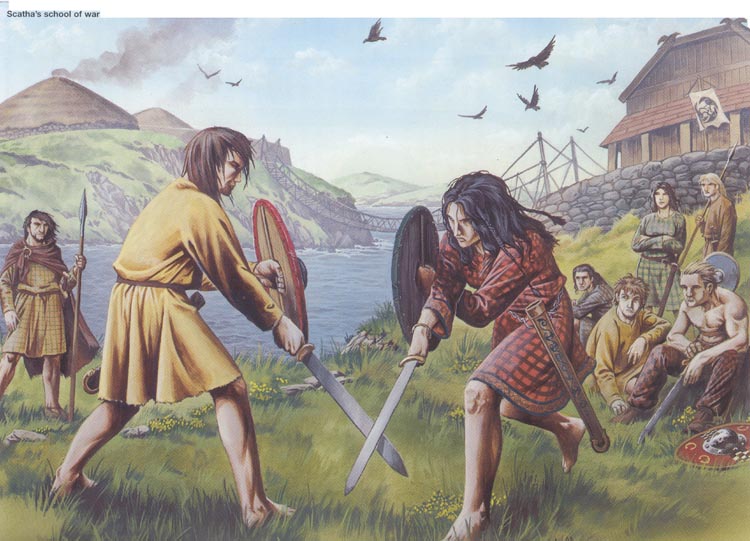

That they maintained truly loving as well as physical relationships is borne out in a mythic context in a truly touching part of the saga of Cuchulainn (pronounced "Ku Kullen"), where he develops an intimate and lasting brotherhood / friendship with one of his peers while undergoing their warrior training on the island of the warrior witch Scathach.

The importance of Cuchualinn, often called the "Celtic Hercules," in the mythology of Irish warrior culture cannot be overstated. Cu Chulainn - Cu, the Hound, of Chulainn - is the most celebrated warrior and the greatest hero of the most heroic age in the history of prechristian Ireland.

In that respect we can see parallels in the tale of Cuchulainn and Ferdia with those of other erotically-bonded mythic or real warrior heroes, such as Achilles and Patroclus, Herakles and Iolaus, Harmodius and Aristogeiton, David and Jonathan, and Alexander and Hephaestion.

The story of Cuchulainn and Ferdia begins, as noted, with their meeting as they study the warrior martial arts on an island between Scotland and Ireland.

The seas around the island are difficult to navigate and most die on the journey there, but any that reach the island are deemed to be strong and worthy to be guided by Scathach, the pre-eminent instructor of the warrior class.

It is on Scathach's island as boys, undergoing that arduous warrior training which we've seen before in institutions like the Spartan agoge, that Cuchulainn and Ferdiad become, like so many other warriors in so many other cultures, 'friends of the heart'.

Based on accounts of the Celts' sexual practices, and on clues still remaining in the myths as written several hundred years later by monks, many modern experts have come to the rather painfully obvious conclusion that what was being depicted between Cuchulainn and his 'heart's companion' Ferdiad was essentially a sexual relationship between two young warriors. It does not take much digging to realize that the relationship was far more than sexual, and was, in fact, deeply emotional.

Years later, the two boys, now grown men, found themselves facing one another as champions on opposite sides of a terrible conflict, and they fought to the death. I do not believe that this was a cautionary tale meant to indicate that male/male relationships must be punished. Quite the contrary. I believe that this served to heighten the myth's pathos within its native context. Such relationships would have been common and well understood by the audience. The ending would have been viewed as truly tragic by a people who understood and valued man/man love. It would not have been seen as retaliatory or moral in nature.

And that it was love there can be little doubt. Cuchulainn mourned his friend with the words

Fast friend, forest companions

We made one bed and slept one sleep

In foreign lands after the fray

Scathach's pupils, two together

We'd set forth to comb the forest.

The entire lament is quite long. The wording leaves no doubt that while their relationship was physical, love lay at the heart of their bond.

|

I loved the noble way you blushed,

and loved your fine, perfect form.

I loved your clear blue eye,

your way of speech, your skillfulness.

Ferdia of the hosts and the hard blows,

beloved golden brooch,

I mourn your conquering arm

and our fostering together.

You were a sight

to please a prince;

your gold-rimmed shield,

your slender sword.

the ring of bright silver

on your fine hand,

your skill at chess,

your flushed, sweet cheek,

your curled yellow hair

like a lovely jewel,

the leaf-shaped belt

you wore at your waist.

You fell to the Hound,

and I mourn, little calf.

The shield didn't save you

that you brought to the fray.

Shameful our struggle,

the grief and uproar!

O fair, fine hero

who shattered armies

and crushed them under foot,

golden brooch, I mourn.

These are words of a lover to a departed one. No parallel exists for a woman anywhere in Celtic myth. In fact, poetry praising women in an ancient Celtic context (as opposed to medieval or modern) is quite scanty when compared with the body of literature describing and praising men.

This leads me to believe that men, specifically warriors, were the standard of beauty, and that relationships between men held a special, cherished place. The bonds of warrior brotherhood were formed early, ran very, very deep, and, as testified in myth, endured throughout life and even to the end of it.

Here is more of the Lament of Cuchulainn for Ferdia, as translated by Thomas Kinsella:

|

Ill-met, Ferdia, like this

-- you crimson and pale in my sight, stretched in a bed of blood, and I with my weapon unwiped. When we were beyond the sea,

I remember when Scathach lifted

Then I said to Ferdia

At the battle-rock on the slope

I stood with fierce Ferdia

|

|

We went in and I slew there

four times fifty raging men.

Ferdia killed Dam Dreimend

and Dam Dilenn -- a cruel crew.

We leveled German's cunning fort

above the wide, glittering sea

and took German himself alive

to Scathach of the great shield.

Our famous foster-mother bound us

in a blood pact of friendship,

so that rage would never rise

between friends in fair Elga.

Sad and pitiful the day

that saw Ferdia's strength spent

and brought the downfall of a friend.

I poured him a drink of red blood!

If you had met your death then

fighting with Greek warriors,

I wouldn't have outlasted you,

I would have died at your side.

Misery has befallen us,

two foster-sons of Scathach

-- I, broken and blood red,

your chariot standing empty.

Misery has befallen us,

two foster-sons of Scathach

-- I, broken and blood red,

and you lying stark dead.

Misery has befallen us,

two foster-sons of Scathach

-- you dead and I alive.

Bravery is battle-madness!

Misery! A pillar of gold

I have levelled in the ford,

the bull of the tribe-herd,

braver than any man.

All play, all sport,

until Ferdia came to the ford

-- fiery and ferocious lion,

fatal, furious flood-wave!

All play, all sport,

until Ferdia came to the ford.

I thought beloved Ferdia

would live forever after me

-- yesterday, a mountain-slope;

today, only a shade.

What we can hear in this lament are echoes of other warriors and other warrior cultures.

For example, Cuchulainn refers to Ferdia as "the bull of the tribe-herd" -- just as the chief Spartan youth of the agoge was called "the leader of the bull calves."

And Cuchulainn speaks to Ferdia's shade, as did Achilles to the shade of his beloved Patroclus.

And like all warriors faced with the death of their beloved, he realizes he would rather have fallen with him than live life without him.

© All material on this site Copyright 2001 - 2011 by Bill Weintraub. All rights reserved.

Want to read more excerpts from The Cattle Raid of Cooley?

Interested readers can click here to read more of the Tain in both Gaelic and in a translation from 1914 -- hardly a gay-friendly era in Ireland or anywhere else.

Here's a sample, as the boyhood companions and lovers Cuchulainn and Ferdia find themselves champions for opposing sides in a mythic dispute and must fight to the death.

Cuchulain: "When we were with Scathach,

For wonted arms' training,

Together we'd fare forth,

To seek every fight.

Thou wast my heart's comrade,

My clan and my kinsman;

Ne'er found I one dearer;

Thy loss would be sad!"

"Good, O Ferdiad!" cried Cuchulain. "It is not right for thee to come to fight and combat with me; for when we were with Scathach and with Uathach and with Aifè, and it was together we were used to seek out every battle and every battle-field, every combat and every contest, every wood and every desert, every covert and every recess." And thus he spake and he uttered these words:

Cuchulain: "We were heart-companions once;

We were comrades in the woods;

We were men that shared a bed,

When we slept the heavy sleep,

After hard and weary fights.

Into many lands, so strange,

Side by side we sallied forth,

And we ranged the woodlands through,

When with Scathach we learned arms!"

Ferdiad: "O Cuchulain, rich in feats,

Hard the trade we both have learned;

Treason hath o'ercome our love;

Thy first wounding hath been bought;

Think not of our friendship more,

Cua, it avails thee not!"

© All material on this site Copyright 2001 - 2011 by Bill Weintraub. All rights reserved.