by

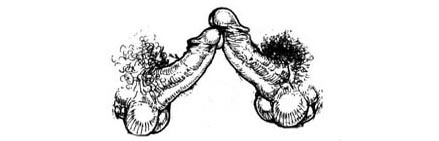

The tribe took the ancient trail from the cold blue mountains to the forest, and to the forest came a goddess to find two women of that tribe. To each she gave a son: to each boy she gave the other.

Theirs was the forest: theirs too its harsh lessons: stealth, stoicism and patience. And in the esteem of the other each had his tutor.

The tribe took the ancient trail from the forest to the cold blue mountains; to the boys came a god to kindle in their hearts the longing. To each he gave desire: to the other its fulfilment.

Theirs was the twilight: theirs too its sweet ardour and the symmetry of loins. And in the eyes of the other each saw his destiny:

"Where you go I shall go. Against the enemies of our people my body is your shield. And under the stars one blanket is ours."

These words wove their togetherness around them. And what the gods have conjoined it is taboo to unbind.

But, in a distant city lived a princess who wanted the forest for her pleasure-garden. Her land was bereft of trees and the rootless earth-sprites she kept in glass jars in her sorcerer's quarters: prisoners of the royal will. One of these she chose for a scout: out flew the sprite from its jar, over the blue mountains and into the forest.

The sprite stole across the two young men asleep beneath a common blanket, and entered one of them. It evicted the native spirit which had dwelt there, which fled in anguish to the stars.

The other young man awoke to a changeling. From this stranger he shrank in horror: "I am forsaken."

"Kill this man," murmured the sprite to its host, "and to you my mistress shall give all the treasures of the earth."

So the changeling fell upon the forsaken one, and raped him.

And the forsaken one limped to the precipice to end his dishonour; and his spirit left the broken body upon the rocks. It too fled in anguish to the stars. There each spirit roamed, crying out for its twin. But neither could find the other.

"Your husband was taken by a wolf," said the changeling to his victim's widow.

"Why do you sneer?" she asked. "Were you the man you appear to be, you would know that such a death would have been without ignominy, for the wolf is sacred." She shook her head. "Though you have his appearance you are not the man my husband loved: your eyes are hard." She stood. "Whoever you are, you cannot win. For the merciful goddess has recovered my husband's spirit, and she has sewn it into my womb."

The changeling laughed, thinking her simple: "When mercenaries ride out against you and against your unborn child: then shall you fear me."

The tribe cast out the changeling, thinking him gone. But sickness set upon the tribe, so that foul waters poured from the mouths of the people, and from their bowels. The young men of the tribe rode out to kill the changeling, saying: "We shall smear our faces with his blood."

They returned naked of weapons and dazzled. "He has taken a wife," they exclaimed, "a princess from a distant city. His wealth is very great. He lives in an impregnable stone house with a wooden spire, and around it is a vast palisade." They waved scraps of parchment: "Come, give up your weapons and claim these promissory notes. For in the changeling's cellar there is gold to be had, and sweet wine to cure the sickness."

Murmuring to her unborn child, the widow turned from this trap and vanished into the forest. For her ordeal the goddess brought sweet herbs. And she bore a son.

The palisade pushed out against the forest and the forest shrank from it. Within it, in its snaking streets, the tribe gasped for air and light. The princess prescribed cheap bread: just enough to pacify them. And grotesque circuses to dazzle their eyes. Some turned from the circus, but too late: they were blind to the stars, and, far from the ancient trail, could grope their way only from the fulfilment of one base desire towards the fulfilment of the next.

The princess devised factions, and young men's blood flowed like wine in the gutters, in wars over trinkets and baubles. And then she came to heal the wounds, and the people cheered.

And in the forest, the widow's son came of age. The purpose of his longing perplexed him, until one night a god came to him and gathered the youth's body to his own. The youth's lips parted and the god's breath entered the youth and gave to him the voice of a man. The loins of the youth stirred against the god's loins, becoming fat and full: and he discovered the purpose of his longing.

But he had no mortal companion, and the yardstick of his longing was the measure of his loneliness.

When the sickness took his mother from him he went to the mountains to pray, and woke to a she-wolf, inches from his nose. He shook and sweated and tried to recall the ancient prayer: "It is a noble death."

But the wolf merely gazed at him. Then she went to the crag to sing but there was no answer, for she too was alone on the face of the earth, the last of the free.

As the last of the free, tribesman and wolf were quarry for the mercenaries: callow urbanites, unwise to stealth, easy to ambush. To keep them from the wolf he killed them. And to give their deaths nobility he left their bodies for her on the forest-floor. Upon each body he found gold coins, and each coin bore the face of its owner: a woman.

His lonely trail led him to the sacred stream, where he knelt to drink. Then a vision came to him, and he found himself again a very small child, unable to clean himself, and ashamed. And again his mother taught him: "There is neither nectar nor ambrosia that can pass through our bodies uncorrupted, for we are mortals. But think: our food is the animals, and their foods are the sweet grasses and herbs, which come from the soil. Therefore, if you return to the soil what you have eaten, the goddess will send her burrowing creatures to make it pure, and the grass shall always grow."

He walked upstream, where he turned and vomited into the grass, as his mother had done after bathing at this place: for he saw the sewage-trench from the town cut into the sacred stream, and he saw what poured from it, into the sacred stream.

Grief turned to fury and his fury to strength. Into the sewage-trench he pushed every boulder and fallen tree that came to hand. He collected the bodies of the mercenaries -- those that lay uneaten -- and these too he threw into the trench. By dusk he had smothered the trench and was within yards of the town. Here the trench vanished under the palisade, to the latrines.

He climbed a tree to watch. The trench shuddered but in the town life kept a mundane pace. Men trudged hither and thither, their eyes never far from their feet. All night steady traffic came to and from the latrines.

"What we need is a storm," muttered the tribesman.

And clouds gathered. They pressed upon the wooden spire of the great stone house at the centre of the town. And a lightning-bolt ate the spire in a prism of light. Fire gnawed at the remains.

Then came the cascade. The contents of the trench rolled back under the palisade, and, reeling at the miasma at its feet, the palisade began to wilt. The latrines sank and the occupants were ejected from their thrones, their bare arses flashing in the gloom as they fell over each other to escape.

Foul waters poured after them.

Two servants of the princess clambered over the fallen palisade to pull debris from the trench. The tribesman hesitated, then pulled two arrows. The servants fell into the trench and were consumed.

Their deaths fed his resolve. He clambered from the tree and walked through the rain into the town, straight for the great stone house. He saw the princess: the woman whose face he knew from coins. The princess saw him and smiled, but black anger flashed unmistakably in her eyes, for here was the last of the free: the man who had cost her too much gold in fallen mercenaries. And he was barely older than her own son.

She was dressed in wolf skin and little else: when she turned a hard wet nipple flashed at him, and hunger gripped his loins. But this was no natural hunger, but a barb she had implanted in him.

"Gold for your weapons, tribesman?" she asked prettily, waving at him a promissory note.

"No? Very well."

She murmured to her men and they advanced upon him. But he raised his eyes to the clouds and one barely audible word fell from his lips:

"Stop."

A god seized the word and turned it over in his hand like a pebble, and nodded his assent.

And the cataclysm died so suddenly that the rain stopped in mid-air, then flocked skywards: and the air was clear.

The tribesman stood in sunshine, radiant. Silence prevailed.

"Seize him!" shrieked the princess.

But her men shrank from the sight of him. Fear shone in their eyes. One shook his head: "I have lived here so long I forgot such miracles were possible."

Said the tribesman: "Even as my mother lay dying from the sickness, she would not let me carry her here: for it is from this place that the sickness issues, and there is no cure in the sweet wine other than the absence of bad water." He peeled from the mud at his feet a scrap of parchment and crumpled it in his hand: "Do this with your promissory notes and you shall be free men."

It was as though he had spat on an idol.

"Honour prevents our leaving," protested one faction of the town, "for we are indebted."

"We owe nothing," claimed another faction. "Our promissory notes are many, and they are worth the gold that is kept in the cellar of the great stone house."

"You are in debt," said the tribesman to the first faction, "because the changeling charges more promissory notes than he gave, to buy for yourselves the things which the forest gives freely."

To the second faction he said: "You who think yourselves free: let us see this gold for ourselves."

The factions of the town looked at each other like sheep, then as one plunged into the stone house.

Then from thin air came the changeling, and though ageless he was as gaunt and white as bones. His belly full of wine, he sang to himself as he closed the door against the people inside his house, and dragged across it a barricade.

Then he turned to the tribesman and smiled, and the tribesman shrank from him in horror.

"I see in you your father's spirit," said the changeling. "And it was at your age that he died: taken by a wolf, do you suppose? Or did he die in agony and despair, with the seed of my loins writhing in his bowels?"

The tribesman moved to strike him down but his limbs were stone. From behind him he heard the changeling's voice in his ear: "Will I allow you to live, do you suppose, or shall I visit upon you the same fate?"

With his supernatural strength the changeling seized him and threw him down and pushed his face into the mud. Silently the tribesman prayed to be killed before the dishonour was forced upon him.

Death came, but not to him: he heard a growl and the weight was gone from his back.

Wiping the mud and tears from his eyes he saw the changeling in the jaws of a dog-wolf.

"It is a noble death," said the tribesman coldly. But the changeling squealed and squirmed and begged for mercy while the wolf toyed with him, merriment in his eyes. Then suddenly disdain shone in the wolf's eyes, and to silence the incessant shrieks of this wheedling creature he fastened his jaws around the changeling's neck and tore out his throat.

Then the wolf called, and more wolves appeared, and together they ran from the town.

The princess followed them into the forest, shrieking: "My wardrobe has escaped! My wardrobe!"

She was never seen again.

The tribesman pulled the barricade from the door of the stone house. Angry men spilled over the corpse of the changeling, saying: "We shall smear our faces with his blood." Then they blew the dust from their weapons and returned to the ancient trail.

The tribesman went to the bankrupt cellar and knew that all its gold lay scattered on the forest-floor among the bones of the mercenaries. He set about burning the house when a faint voice came to him.

And at first glance he thought he saw an animal.

The creature crouched against the wall to which it was shackled, in its own filth. Then it stood on precarious limbs and it was the son of the princess: in height and years equal to the tribesman: in strength unequal.

The tribesman cut the prince free and carried him into the forest. He bathed him and gave him a blanket to cover his nakedness and built around him a shelter and lit for him a fire. Then he brought meat for him, and herbs to strengthen him.

Thus they spent their days together. But they spent them in silence. And each night the tribesman retired to his lonely place, for he had lived so long on his own that he knew no other way.

One day the prince said: "My mother paraded me to the town as her daughter, so that I believed I was a girl. But manhood came and she shut me away. A funeral was held for her daughter. I recall the night I became a man: I dreamt that a god came to me, and -- "

"I think that was not a dream," muttered the tribesman.

"The god never returned," sighed the prince.

The tribesman shrugged. "Perhaps you belong to another," he mumbled.

Again he went that night to his lonely place, and saw the she-wolf. "Hello, old friend," he murmured. She went to her crag and sang and the night shone with wolves, and though he was glad for her, his heart was sore.

That night the prince woke him with these words: "I belong to you."

Angrily, the tribesman turned on him. He expected the prince to slink away. But to his astonishment the prince stood his ground. Gone from his eyes was the weak, half-light of the invalid: ferocity shone in them.

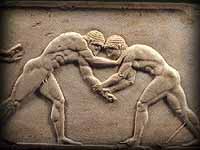

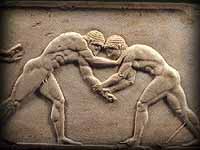

"Do you think that in me there is no anger?" asked the prince. "Nor bitterness? Come, let us knock it out of each other."

And something in the tribesman broke, and seizing the prince by his hair, threw him against a tree.

The prince came about, spat a mouthful of blood, and rushed the tribesman.

And all night they fought but, though brave, the prince was still weak and his blood began to seep from him.

The gods wept.

And the tribesman woke still gripping the prince, and he too wept, for of all the deaths in his short life this seemed the most senseless.

Then a hand gripped his throat and he looked down, into the open eyes of the prince, whose hand moved from his throat to his hair, and in blessed relief his face sank against the prince's neck.

Their loins stirred and their eyes locked and they saw the ancient affinity of their spirits and the end of their loneliness, and it was too much for their loins to bear. And the last barrier between them was swept away.

And from they knew not where, came the words:

"Where you go I shall go. Against the enemies of our people my body is your shield. And under the stars one blanket is ours."

And these words wove their togetherness around them.

AND

Warrior Fiction is presented by The Man2Man Alliance, an organization of men into Frot

To learn more about Frot, ck out What's Hot About Frot

© All material on this site Copyright 2001 - 2011 by Bill Weintraub. All rights reserved.