MANHOOD: A Reductional, Functional, Teleological, Incantational, and, above all, Sanctional --

Lexicon

Hi guy.

Welcome to Biblion Tetarton -- Book IV -- of Manhood: A Lexicon.

My name is Bill Weintraub, and I'm the creator of The Man2Man Alliance and Ares is Lord websites, and the author of Manhood: A Lexicon.

Manhood: A Lexicon is, basically, a book -- masquerading as a webpage.

And, like any book, it's best read from the beginning.

So -- I strongly encourage you to read, if you haven't already, the Prefatory Note and Prolegomena to Manhood: A Lexicon ;

And then Biblion Proton ;

Followed by Biblion Deuteron and Biblion Triton.

It's important that you read that material, and in that order:

Doing so will greatly aid your understanding of the material you encounter in Biblion Tetarton and the rest of Manhood: A Lexicon.

Also:

Biblion Tetarton -- Book IV -- is divided into sections:

WARRIORS AND WARRIORDOMS

FATHER AND KING

ARES - EROS - AGON

MANLY MORAL ORDER

IN UNION WITH VALOUR

Again, it's important that you read all five sections, and in the order given.

July 20, 2013

BIBLION TETARTON

WARRIORS AND WARRIORDOMS

FATHER AND KING

ARES - EROS - AGON

MANLY MORAL ORDER

IN UNION WITH VALOUR

By Bill Weintraub

BIBLION TETARTON

By Bill Weintraub

ςo -- now that we've identified Manhood, Fighting Manhood, with Moral Beauty, Goodness, Nobility, Excellence, Valour, and Worth ; looked at Manhood as the Primal Love, the Highest Value, and Good in Itself ; and begun to understand the process of UN-forgetting that same Absolute Manhood, that Supreme Fighting Manhood --

it's time to ask:

Is Fighting Manhood -- in the form of Struggle and Strife -- Fighting -- Fighting between Men who are, as famed classicist Werner Jaeger says, Struggling to Perfect their Manhood --

Is the Struggle of Manhood Against Manhood, the Fight of Fighting Manhood Against Fighting Manhood -- "the Father of All?"

Because, you see, "Fight is the Father of All" is a saying attributed to the Greek philosopher Heraclitus, who died a few years before Sokrates was born, and so is known as a "pre-Socratic."

In order to answer that question, I need to make some things clear to you, things which should be clear to you already but which, I can tell from what you say to me, are not.

First off, the ancient Greek world -- and the ancient Roman world and the ancient Keltic and Teutonic and Persian etc worlds -- were ALL Warriordoms:

They were all Masculinist and Martial cultures in which the Warrior, and his way of life, was supreme.

And they were, all, and as I've already said in the Prolegomena -- Dominant Cultures -- meaning that they called the shots, they determined what was normative and what wasn't.

Again: Warriordoms were Dominant Cultures -- it was their norms, their standards of behavior and belief, which mattered.

Just so that's really really and crystal clear, let's say it one more time:

Warriordoms were Dominant Cultures -- it was Warrior norms, Warrior standards of behavior and belief, which mattered.

And those Warrior standards of behavior and belief centered, as you've seen, on Fighting Manhood.

That being the case -- and keeping in mind the distinction, discussed in Biblion Deuteron, between the World of Becoming and the World of Being --

ALL MEN of that era lived in a sensible realm -- a world of becoming -- which was a WARRIORDOM -- that is, which centered on Fighting Manhood.

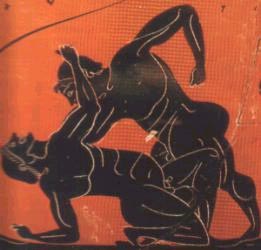

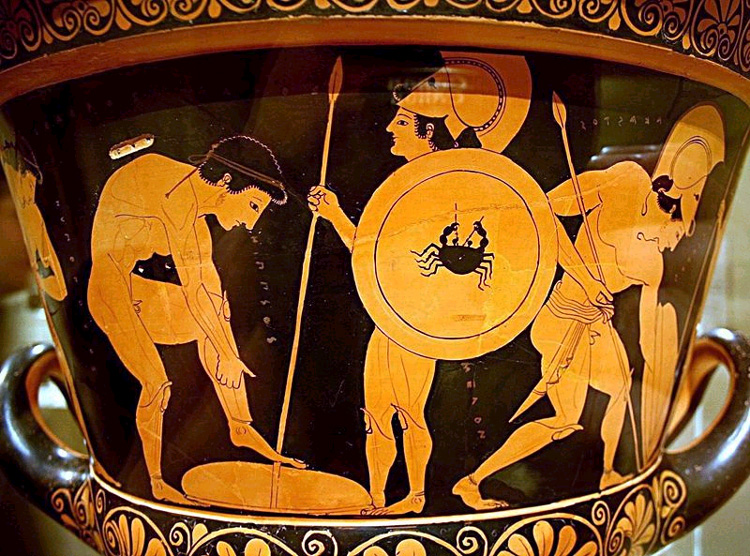

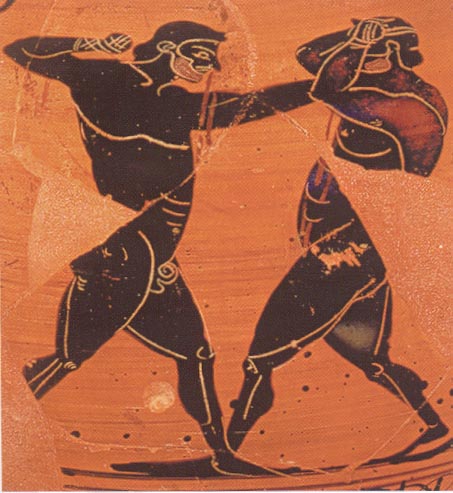

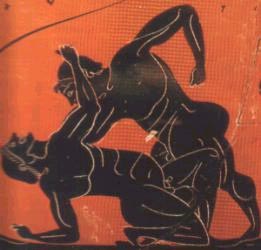

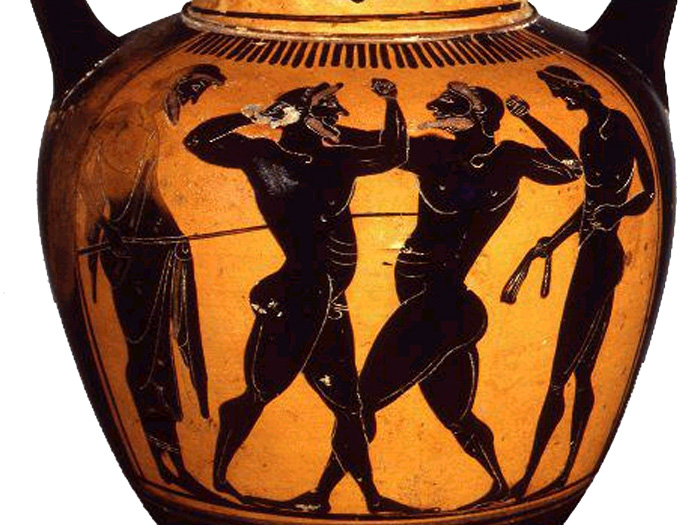

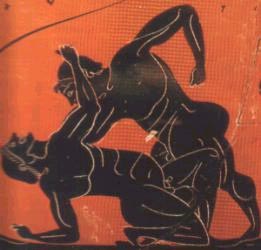

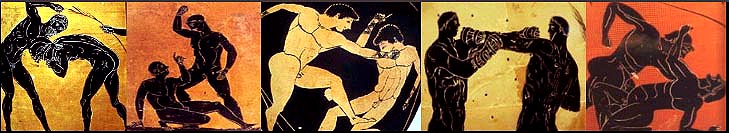

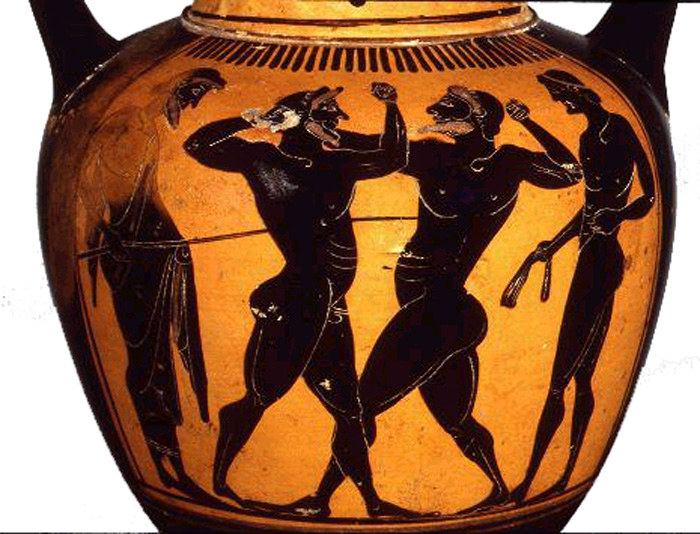

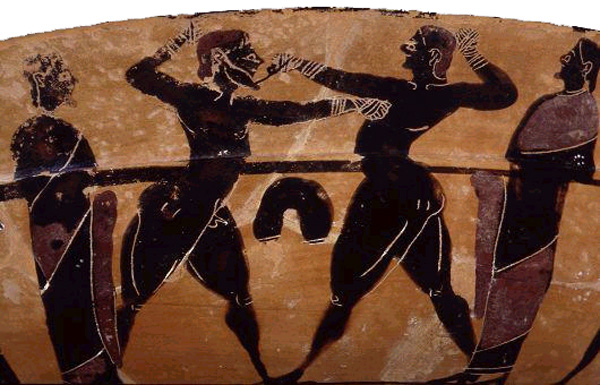

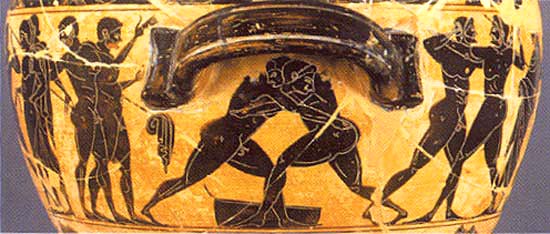

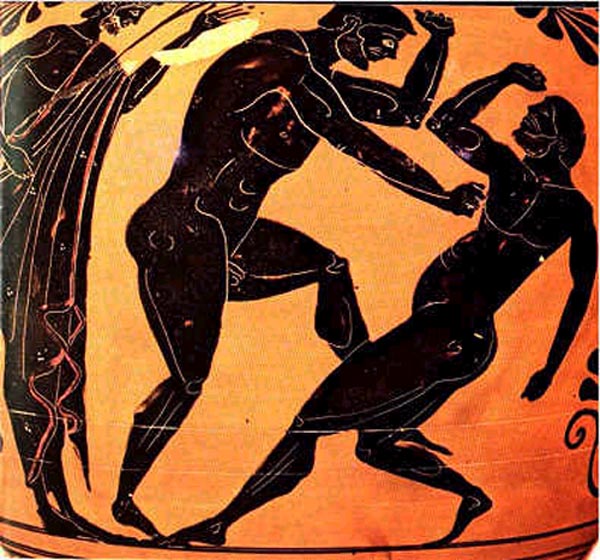

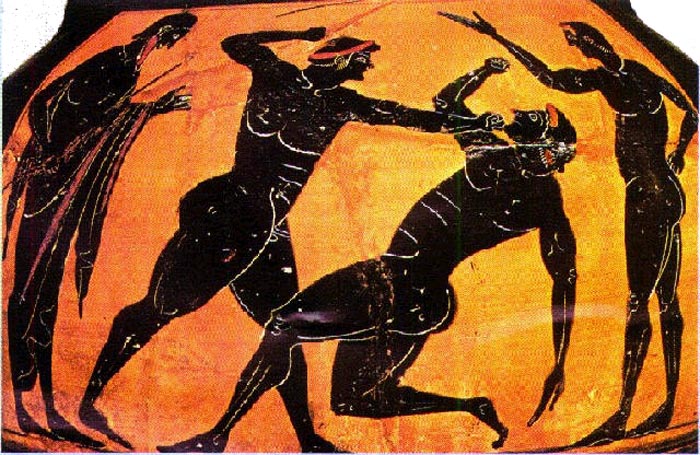

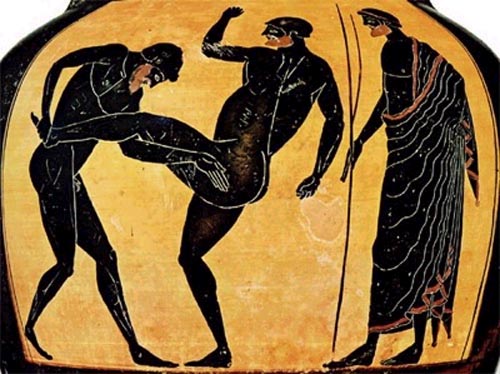

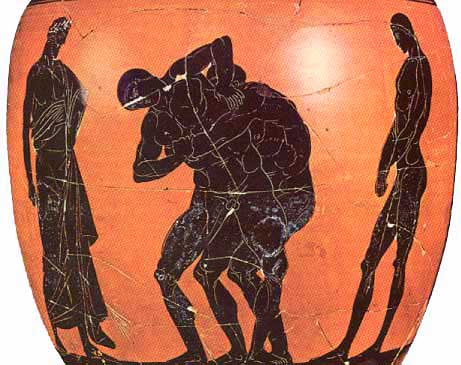

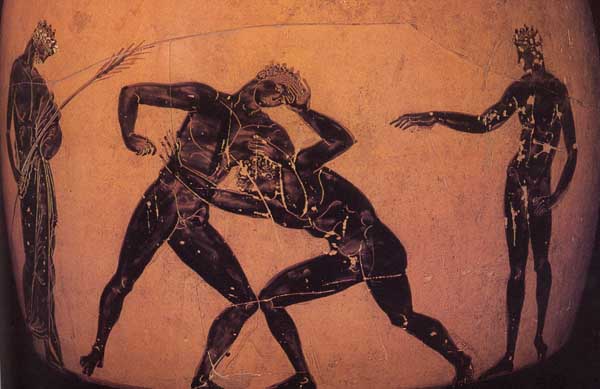

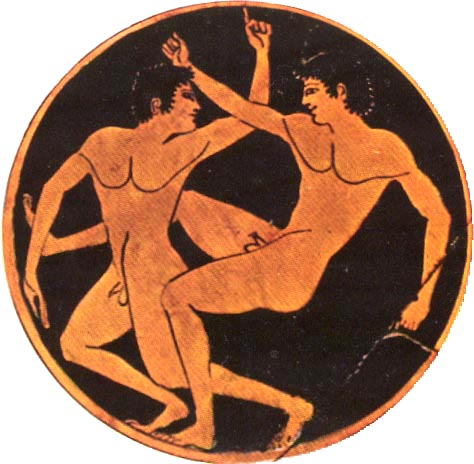

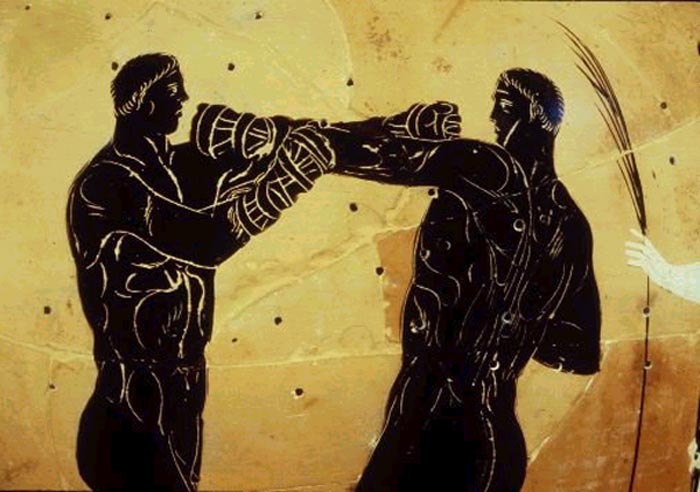

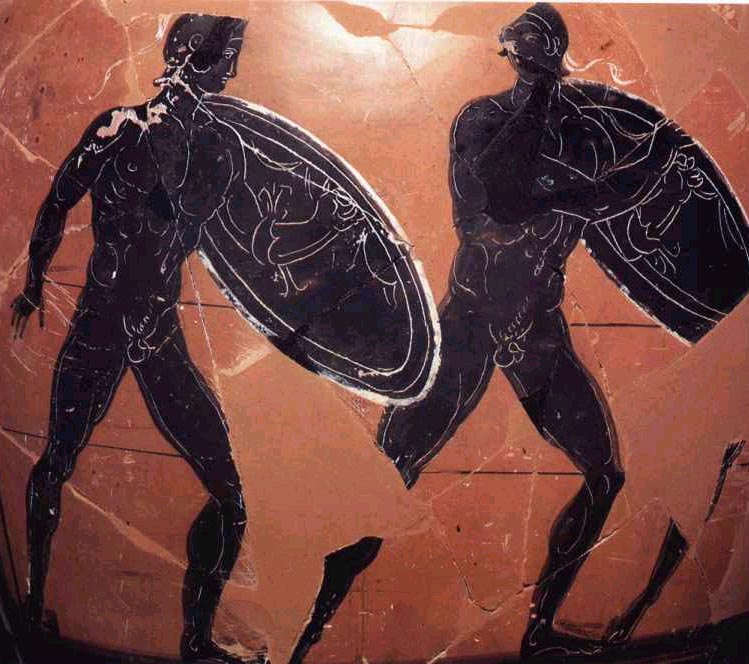

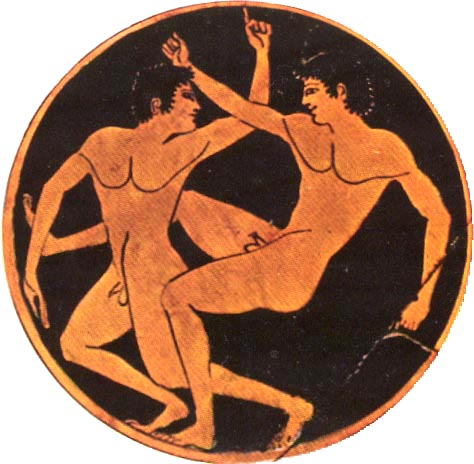

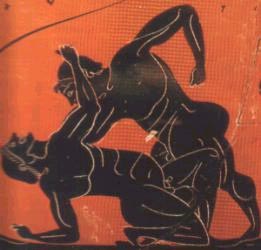

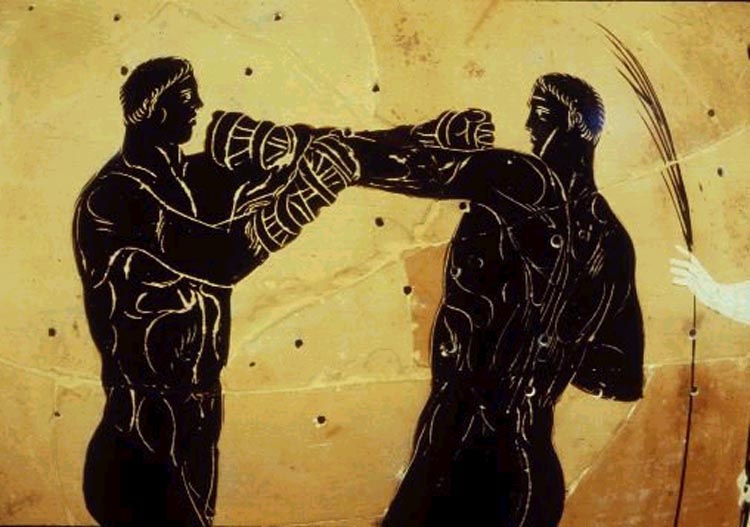

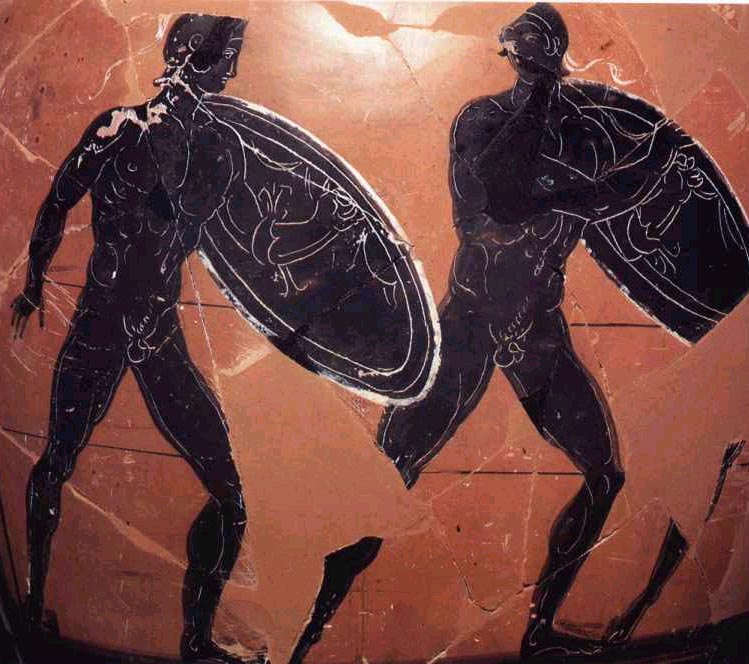

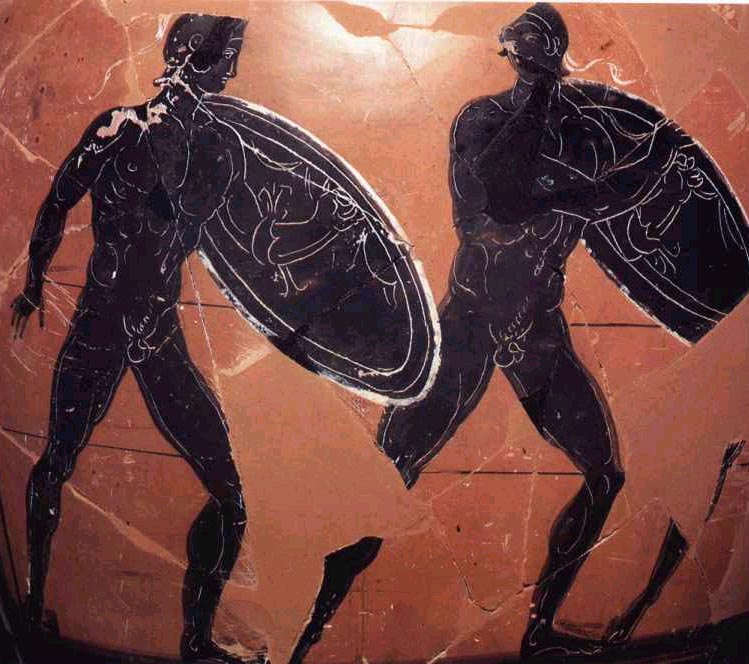

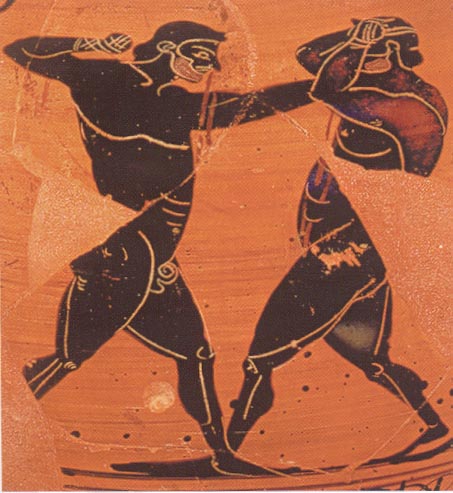

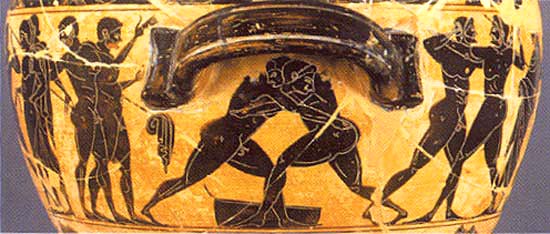

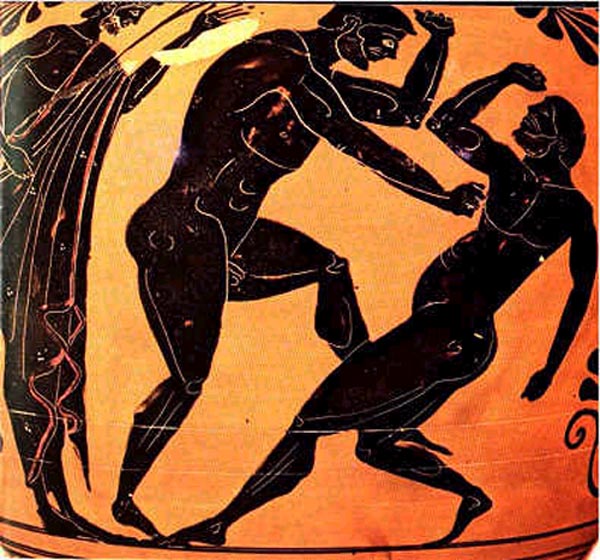

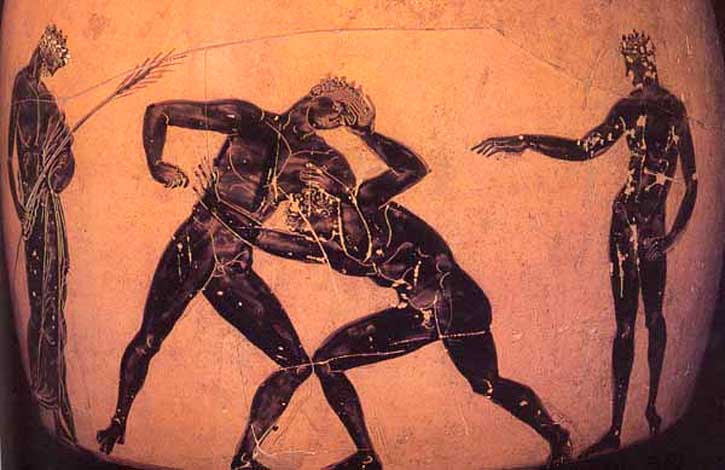

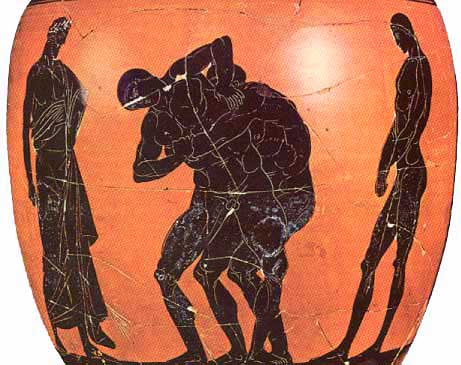

For the Greeks, that Fighting Manhood was expressed in Fight Sport -- nude and unarmed -- and on the battlefield.

Often, as you saw in our discussion of Timé, Fighting on the battlefield was nude also.

But it was armed -- and therefore deadly.

So -- for the Greeks, Fighting was sometimes armed and sometimes not.

For peoples like the Kelts and the Romans, Fighting was usually armed.

There persisted, after Rome conquered Greece, and in the Greco-Roman world, a tradition of Nude Fight Sport --

but what mattered to the Romans -- was knowing how to Fight -- with sword and shield.

But -- regardless of the particulars of how individual Men Fought in the World of Becoming:

The World of Being of virtually ALL MEN was a Warrior Kosmos -- governed by Warrior Ideas, Forms, Essences, and Ideals -- most especially, Fighting Manhood, which was identified with Moral Beauty, Goodness, Virtue, Valour, Courage, Nobility, Prowess, Excellence, Righteousness, and Worth.

As you've seen, and focusing on the Greeks, in the Prolegomena and Bibilon Proton -- and the following Biblia as well.

We today, by contrast, no longer live in Warriordoms -- and, as a consequence, only a very few Men have managed to UN-forget their Manhood and commune with it -- in the Warrior World of Being.

But that was NOT so in the ancient world.

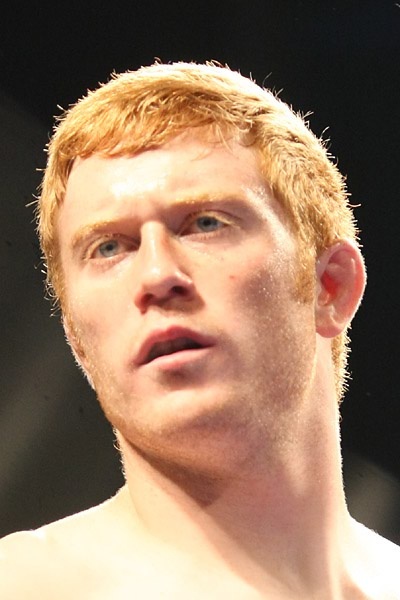

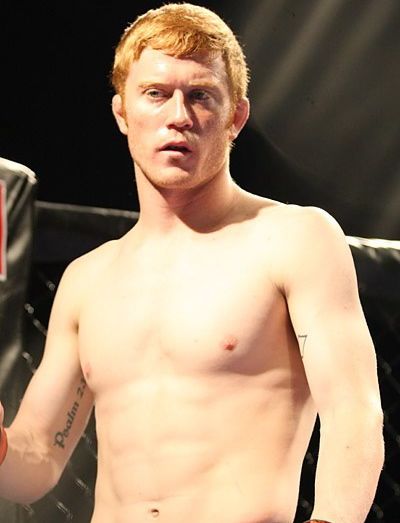

And I know that most of you won't believe me -- because I know for example that to convince even a guy like NW, a guy who's actually trained, and fought, in Fight Sport -- I know that to convince him of the simple fact, for example, that armed single-combat, one-on-one combat with weapons -- was normative in the ancient world of the Romans and the Kelts -- is a struggle.

He just doesn't or can't believe or accept it.

But -- I'm correct.

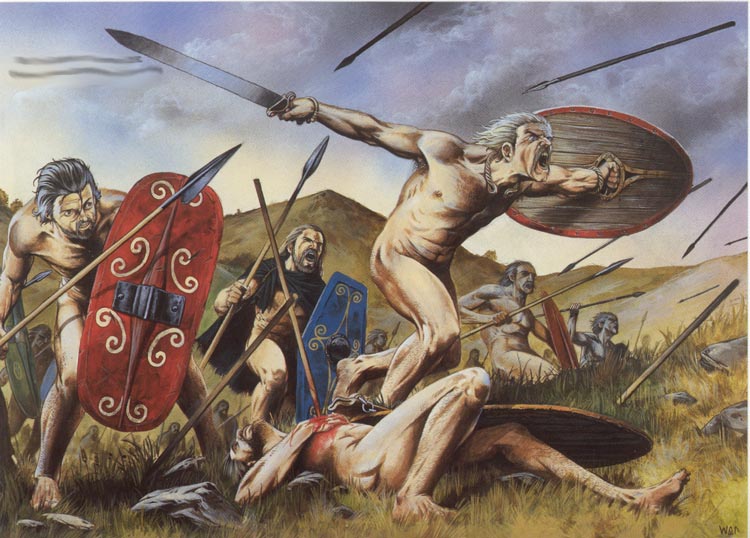

So -- let's take a little time to look at an encounter between two Warriors, one Keltic, the other Roman -- an armed single-combat -- in 359 BC, as described by classicist JE Lendon.

Fighting Manhood.

The Greek word is Areté.

The Latin word is Virtus.

This is a bit of what classicist J E Lendon, whose work we examined in The Secret Craft of Warriorhood, says about Virtus:

Virtus was the root value of Romans of the middle Republic -- Romans wore iron rings to symbolize it -- and like the martial excellence [areté] of the Greeks, virtus was par excellence a competitive quality.

. . .

It was the fiery ambition of Romans, especially young Roman aristocrats, to excel those around them in virtus that led them to seek out single combat.

. . .

[In 359 BC] a vast company of Gauls was camped in the Pomptine country south of Rome. The Gauls, Rome's most feared enemy, had sacked the city [thirty] years earlier, vagrant armies of Gauls wandering over Italy brought frequent panics, and the Gallic attacks had brought Rome's neighbors to the north, the haughty and refined Etruscans, to the verge of destruction. The Roman army marched against the Gauls, but the Roman war leaders, the consuls, were alarmed by the number and strength of the ancestral foe.

. . .

[A] gigantic Gaul -- "naked except for his shield, two swords, torque [metal collar], and arm-rings" -- had challenged the Romans to send forth a champion to face him. "No one dared because of his size and savage appearance. Then the Gaul began to laugh at them and stick out his tongue." Offended at the insult to his country, the young Titus Manlius answered the challenge, and when the Gaul came on singing, the Roman rammed the barbarian's shield with his own, driving him back and throwing him off balance, eventually getting under his guard and stabbing him in the chest and then the shoulder with his sword. "When he had overthrown him, he cut off his head, dragged off his torque, bloody as it was, and put it around his own neck. For this act he and his posterity bore the nickname 'Torquatus,' " the Torqued one.

~J E Lendon, Soldiers and Ghosts: A History of Battle in Classical Antiquity

So let's talk about the Gauls -- that is, the Kelts -- and the Romans a bit.

Lendon says that the Kelt was "naked except for his shield, two swords, torque [metal collar], and arm-rings."

And that's correct.

The Kelts, like the Greeks, Fought Nude.

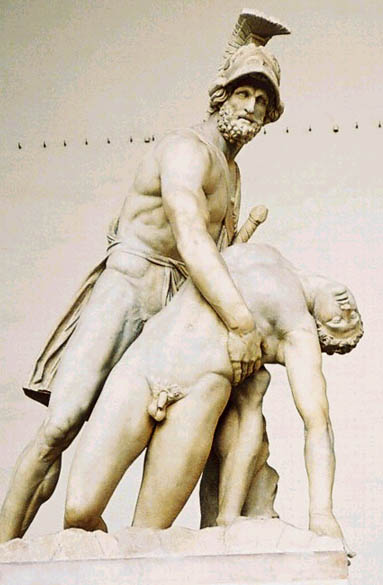

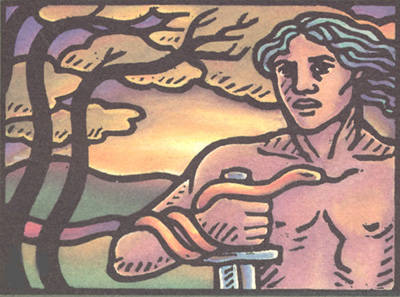

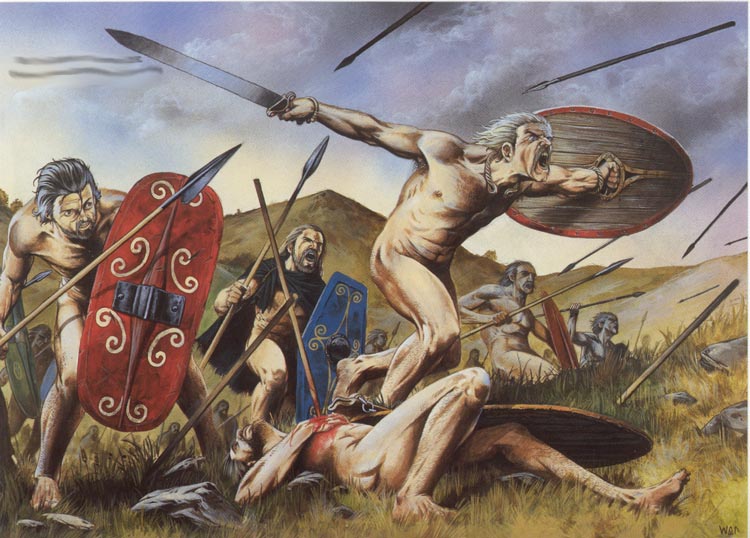

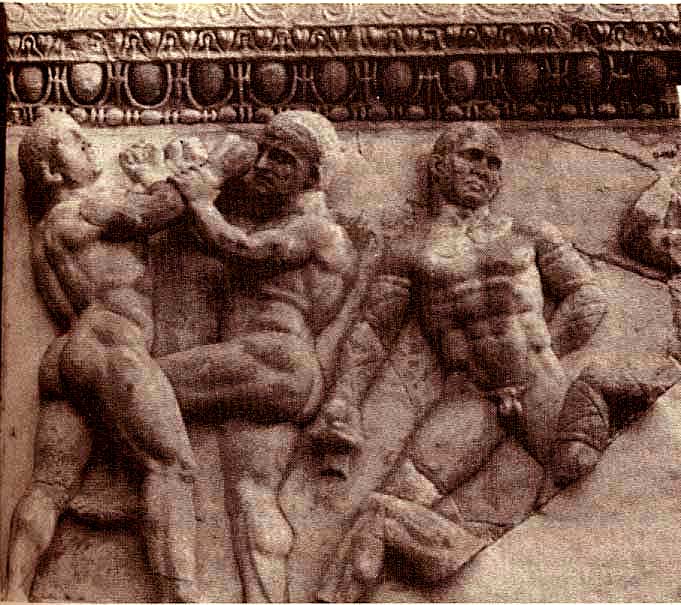

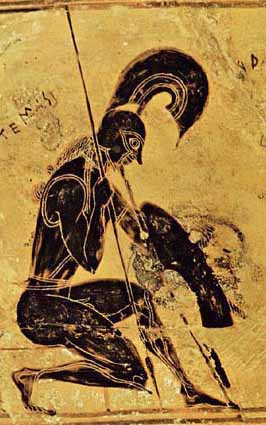

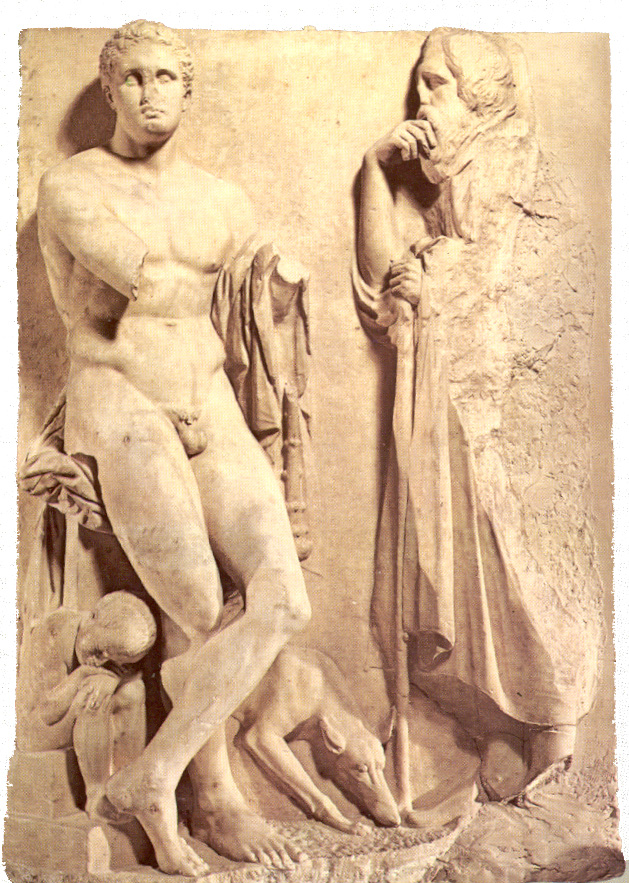

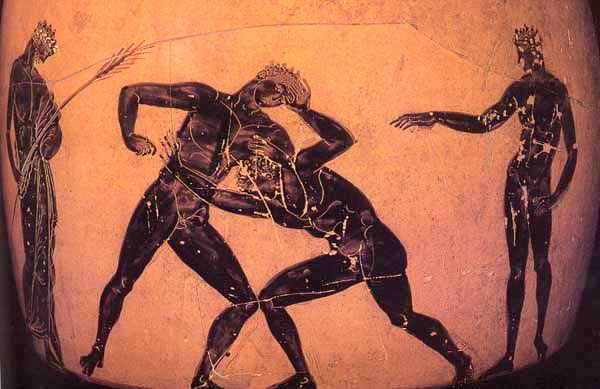

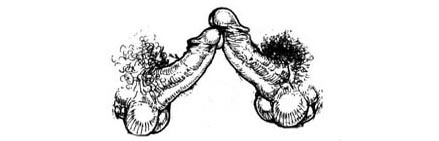

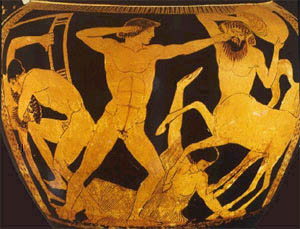

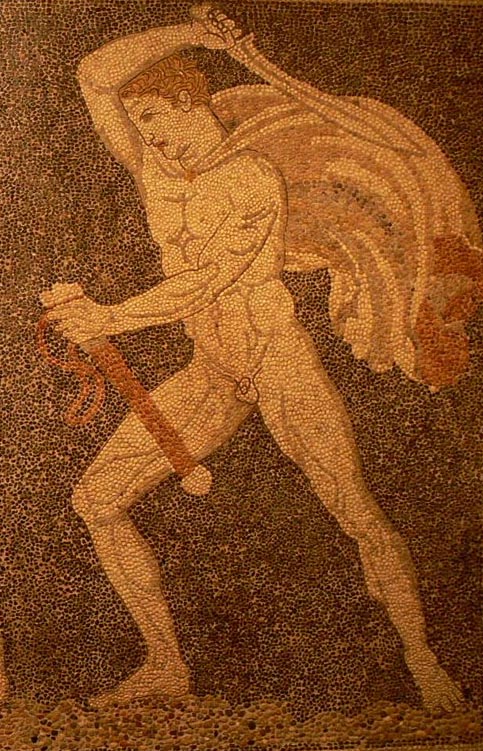

This is a Greek sculpture of a Keltic Warrior:

This is also Greek:

The Kelts, like the Greeks, Fought Nude.

Which means that whatever the Keltic word for Timé -- Worth -- may have been -- Nude Combat added to it.

To a Kelt, Fighting Nude added to his Worth.

Which is Manhood.

Now: these are torques -- the gold collars which the Kelts wore:

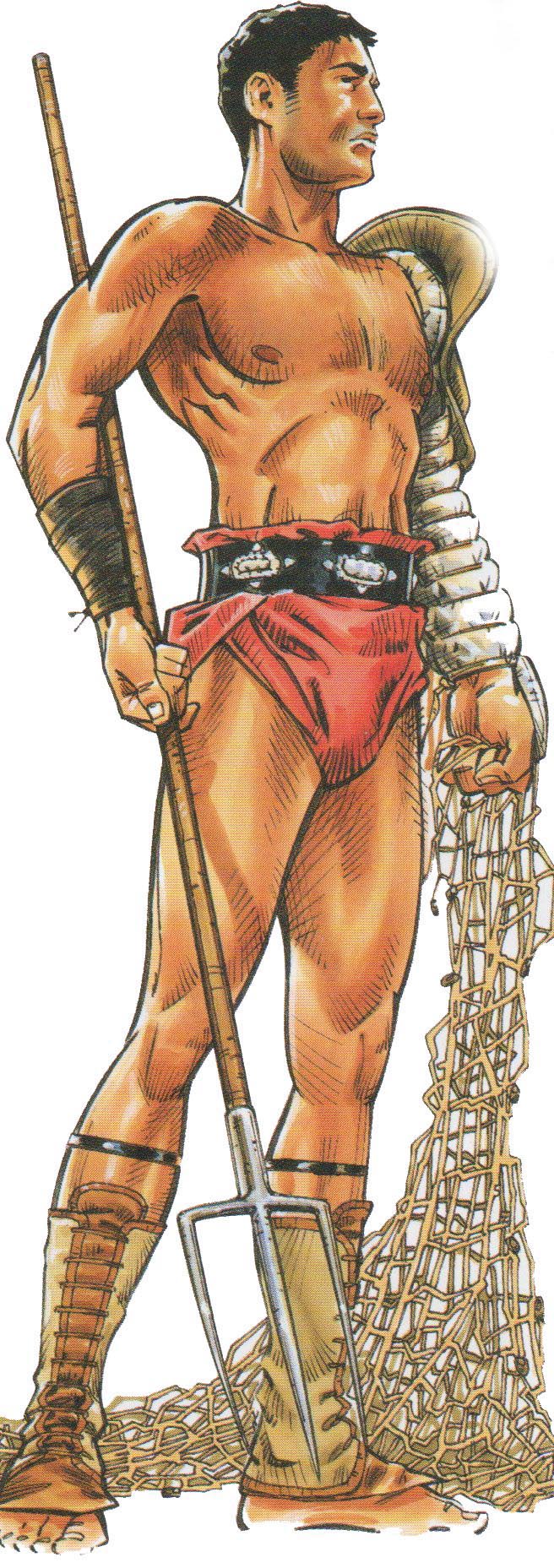

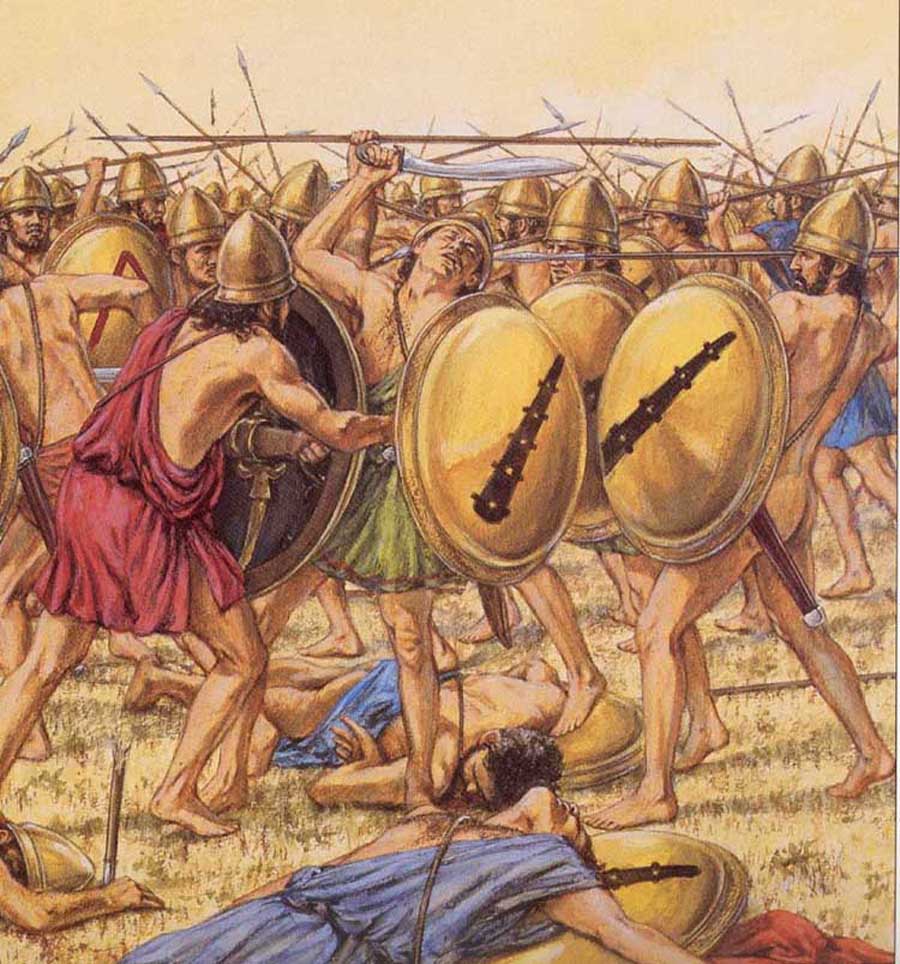

And then we have this artist's conception:

The central figure in this battle scene could well be the Keltic Champion who taunted Titus Manlius:

Notice his torque, his arm-rings, his sword and shield, and of course his nudity, very much as the Roman historian has described:

This is a Hellenistic sculpture of a dying Celtic Warrior -- the Man Titus Manlius fought may well have looked like this Man:

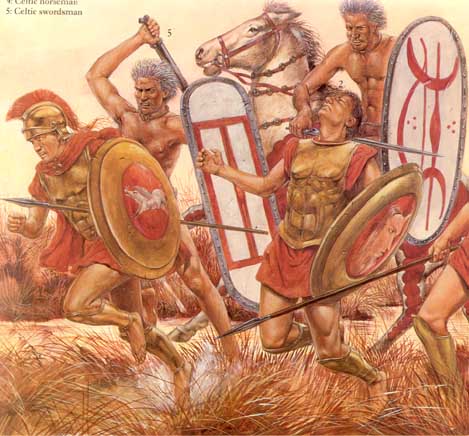

Here are two more nude Kelts, attacking and killing Romans:

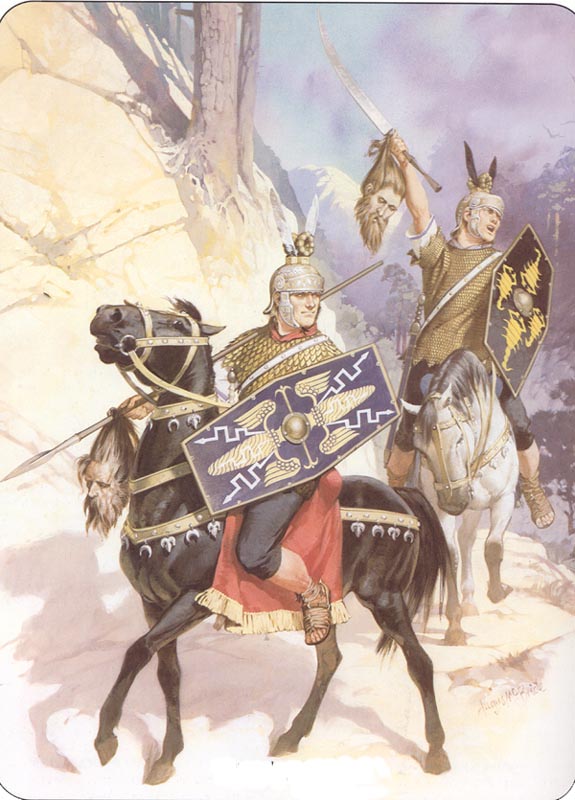

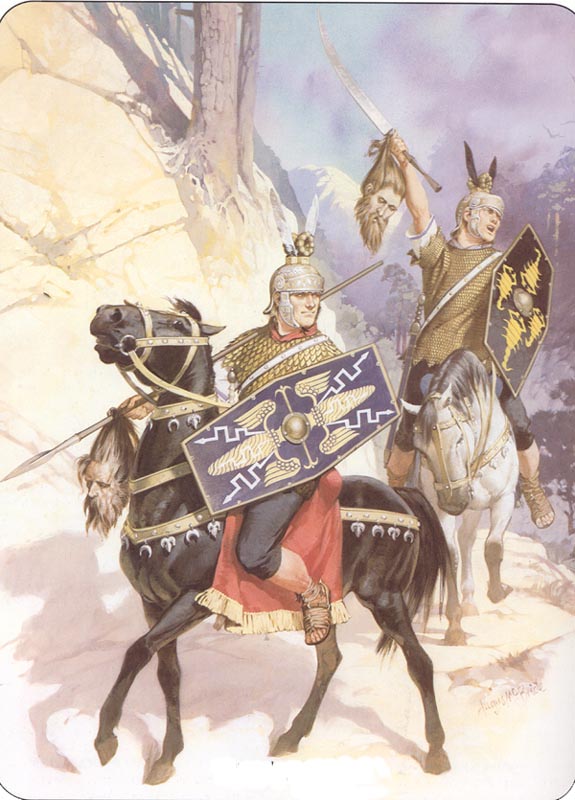

And now we fast forward about 500 years, from the time of Titus Manlius in 359 BC to about 150 AD.

Gaul has been conquered and Romanized, and these are Romanized Kelts who are in the Roman army.

But they're still, in good Keltic fashion, collecting the heads of their enemies:

Because that what the Kelts of Gaul did -- before the Romans "civilized" them.

They engaged in one-on-one armed combats with their enemies, and, when victorious, cut off the head of the dead man, pickled it, and kept it on a shelf in their homes -- which were huts.

That's what the Kelts did.

They engaged in one-on-one armed combat.

Among themselves.

And with Romans and other foreign foes.

Now:

While I know this tale of Titus Manlius and the Kelt will bother some folks of Keltic extraction --

we need to see what was happening in context.

This was hundreds of years before Julius Caesar conquered Gaul.

At this point, the Kelts were the aggressors.

They'd invaded Italy, they'd sacked Rome, and they were rampaging.

They were dangerous and they were scary.

The average Kelt was physically larger than the average Roman, the Romans could not be said to be technologically more advanced than the Kelts -- indeed, the Roman sword, the gladius, was Keltic in origin -- and the Kelts were fierce fighters.

So -- when Titus Manlius met the Keltic challenger, he was demonstrating -- both Men were demonstrating -- Virtus -- Martial Courage -- which is Fighting Manhood.

In the context, as Lendon says, of

a heroic culture not too far distant from the military culture depicted in the [great Greek national epic, the] Iliad but even more ceremonious and ritualized.

Which means that not just the two cultures, Greek and Roman -- but the *three* cultures -- Greek, Roman, and Kelt -- were very similar.

Very very similar.

As are many -- almost certainly most -- Warrior cultures.

Warriordoms.

Which at one time covered the world.

The young Warriors in those cultures were aggressively competitive.

Lendon:

[the young Roman Warrior] regarded his comrades as his competitors in aggressive bravery.

"Aggressive Bravery" --

Prof Lendon really has a way with words, and "Aggressive Bravery" is a terrific characterization of a Manly trait:

Like Brave Beauty, Aggressive Bravery is another definer of and marker for Manliness -- for Fighting Manhood.

And, Lendon adds:

Thus the Aggressiveness of young Men at War.

The Romans of the Republic had a problem balancing the Aggressive Bravery of Virtus -- Fighting Manhood -- with disciplina -- staying within the phalanx as ordered.

Because their aggressively brave young Warriors would break ranks to seek out One-on-One Combat with aggressively brave Warriors from the opposing force.

Lendon:

The Romans believed "that for young men to disobey [that is, break ranks] and fight against orders was justly punishable but at the same time right and natural" -- an expression of Virtus -- Manhood -- Martial Courage -- Manly Excellence -- Manly Goodness -- Manly Virtue.

So -- To the Romans, and clearly to the Kelts and Greeks as well, what the Romans called Virtus was "right and natural," a right and natural expression of the young Warrior's innate Fighting Manhood, Aggressive Bravery, Moral Beauty, Brave Beauty -- in the service of his country, his family, his friends, his ideals -- and himself.

Do you understand?

At one time, all the world was a Warriordom -- or, if you prefer --

Competing WarriordomS -- plural.

Greek, Macedonian, Roman, Kelt, Teuton, Dacian, Scythian, Persian, etc.

ALL MEN lived in Warriordoms.

And when those Men met, they Fought.

Because:

The World of Being -- the ideational world -- of virtually ALL of those MEN was a Warrior Kosmos -- governed by Warrior Ideas, Forms, Essences, and Ideals -- most especially, Fighting Manhood, which was identified with Moral Beauty, Goodness, Virtue, Valour, Courage, Nobility, Prowess, Excellence, Righteousness, and Worth.

And that comes through repeatedly in ancient literature, including in the writing of Plato, who we today think of not as a Warrior, but as a philosopher.

Nevertheless, he was a Warrior as well, and that's apparent in his writing, with its frequent focus on the training and lives of Fighting Men.

However -- before talking about Plato the Warrior, let's fast forward a couple thousand years so as to make clear to you that the culture of sword-fighting and one-on-one armed combat described by Prof Lendon and myself -- persisted for centuries -- long after Hellenism -- what Christians call "paganism" -- had been done in by those same Christians.

So -- let's take a brief look at John Milton, a Puritan poet and pamphleteer, and a member of Cromwell's anti-monarchist government, who lived from 1608 to 1674, and who created one of the greatest poems in the English language, Paradise Lost.

But long before he published, in the 1660s, that poem, he'd written, in 1644, when he was thirty-five years old, a Tractate of Education.

His plan for educating English youth under the new Puritan government is in many ways, including in its emphasis on single-gender living and communal life, quite Spartan ; relies heavily on Classical Greek writers; seeks to produce Men who are Virtuous, Valorous, and, as he'd say, Heroick; and emphasizes Fighting with Swords -- and Wrestling:

Now will be worth the seeing what exercises and recreations may best agree, and become these studies.

The course of Study hitherto briefly describ'd, is, what I can guess by reading, likest to those ancient and famous Schools of Pythagoras, Plato, Isocrates, Aristotle and such others, out of which were bred up such a number of renown'd Philosophers, Orators, Historians, Poets and Princes all over Greece, Italy, and Asia, besides the flourishing Studies of Cyrene and Alexandria. But herein it shall exceed them, and supply a defect as great as that which Plato noted in the Common-wealth of Sparta ; whereas that City train'd up their Youth most for War, and these in their Academies and Lycaeum, all for the Gown, this institution of breeding which I here delineate, shall be equally good both for Peace and War.

Therefore about an hour and a half ere they eat at Noon should be allowed them for exercise and due rest afterwards : but the time for this may be enlarged at pleasure, according as their rising in the morning shall be early.

The Exercise which I commend first is the exact use of their Weapon [sword], to guard and to strike safely with edge, or point ; this will keep them healthy, nimble, strong, and well in breath, is also the likeliest means to make them grow large and tall, and to inspire them with a gallant and fearless courage, which being temper'd with seasonable Lectures and Precepts to them of true Fortitude and Patience, will turn into a native and heroick valour, and make them hate the cowardice of doing wrong. They must be also practis'd in all the Locks and Gripes of Wrastling, wherein English men were wont to excel, as need may often be in fight to tug or grapple, and to close. And this perhaps will be enough, wherein to prove and heat their single strength.

The interim of unsweating themselves regularly, and convenient rest before meat may both with profit and delight be taken up in recreating and composing their travail'd spirits with the solemn and divine harmonies of Musick heard or learnt . . .

~ text from archive.org

So -- the duel between Titus Manlius and the Kelt took place in 359 BC.

Yet, and literally, two millenia later -- two thousand and three years, to be exact -- John Milton is still talking about teaching youths to be proficient in swordsmanship, and in Wrestling, "as need may often be in fight to tug or grapple, and to close."

The Spartans -- and other ancient Greeks -- would have agreed.

So you can see that the culture of one-on-one sword Fighting and Wrestling -- had persisted long beyond the ancient world.

That doesn't mean, however, guys, that the Men of Milton's time would have thought as did the Men of Plato's and Plutarch's.

Christianity had greatly changed the way Men thought.

Just think, for example, of the ubiquitous Nudity of Ancient Men -- and how Christianity had shamed and legislated that -- out of existence.

As it had the True and Valorous Love of Fighting Man for Fighting Man.

So -- what concerns us here is the Pristine World of Flesh and Spirit -- which preceded Christianity's anti-masculinist shame, guilt, and oppression of the Male.

Which means it's time to get back to the pre-Christian, Manly, Ares and Eros worshipping, Warriordoms of the ancient world.

I said, regarding the Men of those ancient Warriordoms, that they Fought -- frequently.

Because:

The World of Being -- the ideational world -- of virtually ALL of those MEN was a Warrior Kosmos -- governed by Warrior Ideas, Forms, Essences, and Ideals -- most especially, Fighting Manhood, which was identified with Moral Beauty, Goodness, Virtue, Valour, Courage, Nobility, Prowess, Excellence, Righteousness, and Worth.

And that comes through repeatedly in ancient literature, including in the writing of Plato, who we today think of not as a Warrior, but as a philosopher.

Nevertheless, he was a Warrior as well, and that's apparent in his writing, with its frequent focus on the training and lives of Fighting Men.

For example, there's Plato's statement in the Timaeus, a book written after the Republic, that having designed his ideal Republic, what he would most like to see is how that Republic performs at War:

Socrates

Timaeus

Socrates

Timaeus

Socrates

Timaeus

Socrates

Timaeus

Socrates

Timaeus

Socrates

Plat. Tim. 17c-18b, translated by Lamb.

So -- Plato spends a lot of time describing a communal way of training and of life for his Guardians, a training and way of life very similar to that of the Spartans; and says that the Guardians are to live communally, and free of private property, thus facilitating among them both fellowship and unceasing devotion to Virtue -- which is Manhood.

Think about that.

Plato is saying that Warriors who live together, free of private property -- and of wives and children too, by the way -- will live in fellowship and unceasing devotion -- to Manhood.

Which, remember, is an ideal.

Plato then goes on to say, via Sokrates, that

Plato's concept of Manhood, as expressed here, is the ancient concept of Manhood and it's absolutely correct.

Men, like other creatures, he says, should be

And for Men, of course, that's Fighting.

Men, properly trained -- which includes training in Fight Sport -- and educated, then create the ideal State, which contends

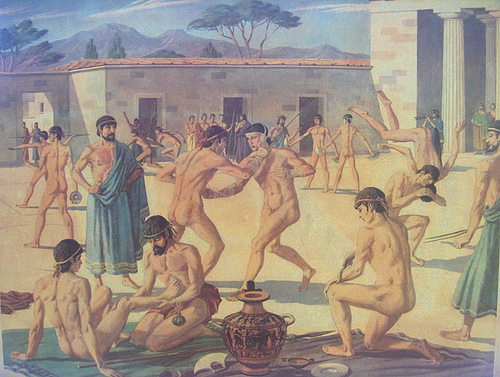

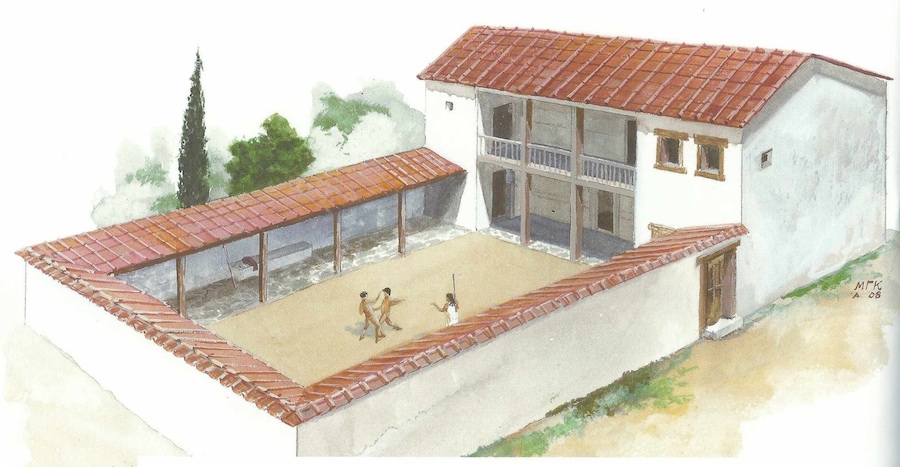

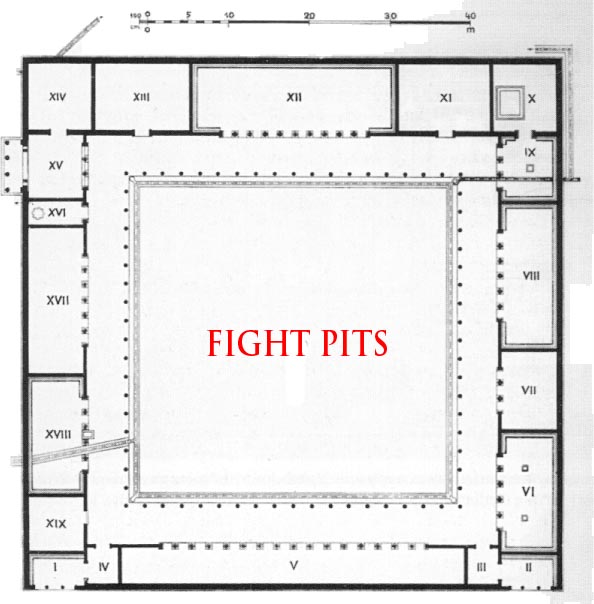

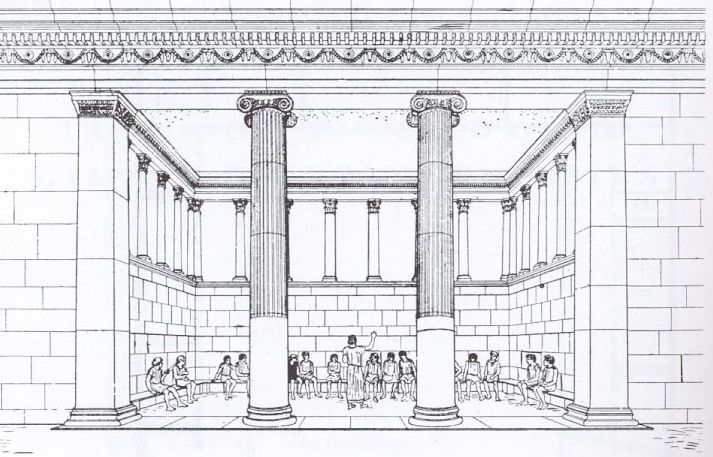

Indeed, throughout the Republic, Plato, in describing the education of his Guardians, his Warrior caste, refers specifically to the traditional physical training, the nude physical training, the gymnastika -- from gymnos (γυμνος), nude -- which was practised throughout Greece at the palaistrai (παλαιστραι), and which Plato says will make his Warriors "athletes of war" [athletes polemos αθλητης πολεμος].

Why was war so important to Plato?

The short answer is that he was an ancient Man.

And for Men like himself, war wasn't something which took place far away, overseas, carried out by drones and bombs and helicopters.

It wasn't.

War was always near, it was fought, more often than not, face-to-face and hand-to-hand, and the loser in a war was likely to be either killed or enslaved -- as would be his entire family, women and children too, and the rest of his fellow citizens.

So -- war -- and the ability to fight -- mattered.

Consider, for a moment and in that light, Plato's early years, not as an inquisitive youth nor scion of a wealthy and politically well-connected family nor brilliant student -- but as an Athlete-Warrior, and as described by the very hard-headed classicist Paul Shorey.

Let's begin by noting that the name "Plato" probably means "broad-shouldered"; and that there is, says Shorey, "a tradition of athletic victories" attributed to him.

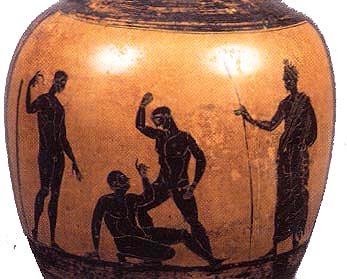

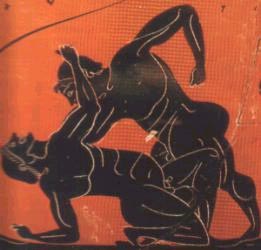

Whether that tradition is correct or not, we know that Plato, as a boy and youth, would have trained at the palaistra and, like Xenophon's Autolycus and Sokrates' Charmides, Lysis, and Alkibiades, competed in athletics nude -- and that the bulk of the training and competition would have been in Fight Sport -- Wrestling, Boxing, and Pankration.

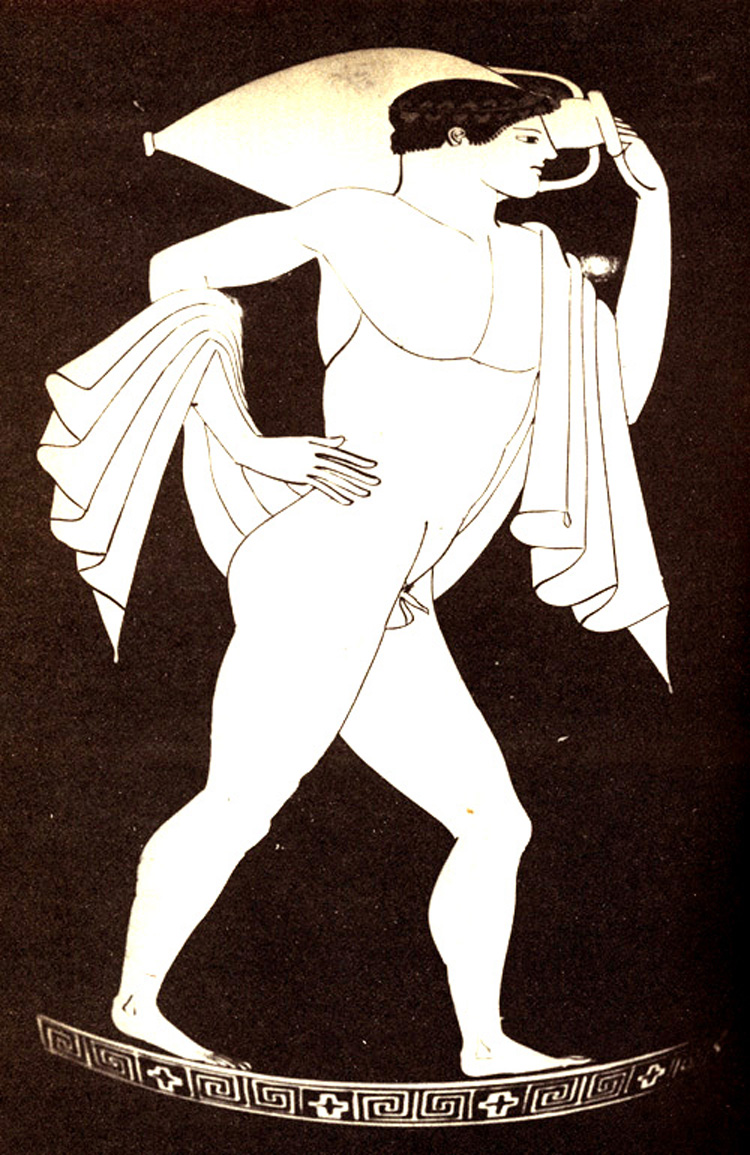

Along with what we would call "track and field," which included the "hoplites dromos" -- a race run genitally nude, but in hoplite armor:

Then there's Plato's military service.

Plato is thought to have been born in 427 BC -- which means that he lived through much of the Peloponessian War, and that he would have come of age in 409 BC -- when he was 18 -- and would have "entered as an ephebos [a recruit aged 18 to 20] the calvary which guarded much of the immediate environment [of Athens] against Spartan raids" from the "thirteen miles distant [Spartan] fortress of Dekeleia."

He would then "have fought in an undetermined battle of Megara [perhaps also in 409 BC], in which, he says in the Republic [368a], his brothers Glaucon and Adeimantus distinguished themselves."

In 406 BC, Plato would "have served in the fleet at the battle of Arginusae, where the Athenian victory was marred by the failure to recover the bodies of the dead in the storm that followed."

In 405 BC, Plato, along with his fellow citizens, would have learned of the annihilation of the Athenian fleet at Aegospotami and the approach of the Spartan fleet and army of occupation, and would have had to wonder, like any citizen of a defeated city-state, if he was going to be killed and his family and friends enslaved by the victors.

Think I'm making that up?

I'm not:

[Philocles "had ordered the crews of two captured [Spartan-allied] triremes to be thrown over a precipice"; and, according to Xenophon, had sponsored and/or supported a decree in the Athenian Assembly mandating that the right hand (Scott-Kilvert says it was the right thumb) of every Spartan and Spartan-allied prisoner of war be cut off.]

But he [Philocles], not one whit softened by his misfortunes, bade him [Lysander] not play the prosecutor in a case where there was no judge, but to inflict, as victor, the punishment he would have suffered if vanquished. Then, after bathing and putting on a rich robe, he went first to the slaughter and showed his countrymen the way, as Theophrastus writes. After this, Lysander sailed to the various cities, and ordered all the Athenians whom he met to go back to Athens, for he would spare none, he said, but would slaughter any whom he caught outside the city.

He took this course, and drove them all into the city together, because he wished that scarcity of food and a mighty famine should speedily afflict the city, in order that they might not hinder him by holding out against his siege with plenty of provisions.

~Plut. Lys. 13.2, translated by Perrin.

. . .

And now, when he [Lysander] learned that the people of Athens were in a wretched plight from famine, he sailed into the Piraeus, [the port of Athens,] and reduced the city, which was compelled to make terms on the basis of his commands.

. . .

Lysander, accordingly, when he had taken possession of all the ships of the Athenians except twelve, and of their walls, on the sixteenth day of the month Munychion, the same on which they conquered the Barbarian in the sea-fight at Salamis, took measures at once to change their form of government.

And when the Athenians opposed him bitterly in this, he sent word to the people that he had caught the city violating the terms of its surrender; for its walls were still standing, although the days were past within which they should have been pulled down; he should therefore present their case anew for the decision of the authorities, since they had broken their agreements. And some say that in very truth a proposition to sell the Athenians into slavery was actually made in the assembly of the [Spartan] allies, and that at this time Erianthus the Theban also made a motion that the city be razed to the ground, and the country about it left for sheep to graze.

[Sounds harsh, doesn't it?

But the Athenians had actually done worse to other cities, and on a number of occasions.

For example, Perrin notes that

The island and city of Melos were captured and depopulated by the Athenians in the winter of 416-415 B.C.

The city of Scione, on the Chalcidic peninsula, was captured and depopulated by the Athenians in 421 B.C.

"depopulated" means the men were killed and the women and children sold into slavery.

So -- it's not surprising that the Spartans and their allies considered doing the same to the Athenians.

And remember what Prof Lendon said regarding Athens and Timé in our discussion of Timé and the Battle of Sphakteria in Biblion Proton:

The whole structure of honor in warfare -- which in this case was by and large the Timé -- the Worth which accrued to a Man -- and a city -- through victory in Manly warfare, that is, in hand-to-hand combat -- had been "cast down" -- by the Athenians.

So: During the Peloponessian War, the Athenians were guilty both of murderously barbarous conduct towards other Greeks ; and of behavior which had the effect of destroying the structure and concept of honor in warfare among the Greeks --

Which is why, after the defeat at Aegospotami, the Athenians wondered, and with good reason, whether what they'd done to so many others -- would now be done to them.

But -- it wasn't, and for the most poetical of reasons, as Plutarch explains:]

Afterwards, however, when the [Spartan and allied] leaders were gathered at a banquet, and a certain Phocian sang the first chorus in the 'Electra' of Euripides, which begins with:

0 thou daughter of Agamemnon,

all were moved to compassion, and felt it to be a cruel deed to abolish and destroy a city which was so famous, and produced such poets.

So then, after the Athenians had yielded in all points, Lysander sent for many flute-girls from the city, and assembled all those who were already in the camp, and then tore down the walls, and burned up the triremes, to the sound of the flute, while the allies crowned themselves with garlands and made merry together, counting that day as the beginning of their freedom.

~Plut. Lys. 15.4, translated by Perrin.

Plato then lived through many years of civil turmoil at Athens, including both the discreditable reign, in 403 BC, of the "Thirty Tyrants," some of whom were his relatives, and many of whom were killed by a resurgent democracy, and the trial and execution, in 399 BC, of Sokrates.

Also by the resurgent democracy.

Plato is then said to have fought in the Corinthian War of 395 to 387 BC.

Translation:

Plato was not some professorial wimp.

He was a broad-shouldered Warrior-Athlete who, like any other Greek of his generation, knew what war was ; and who saw service in several campaigns -- starting as an ephebe in 409, and continuing to 387 -- that is, for twenty-two years.

Not unusual for a citizen-soldier of a Greek city-state.

Which was, again and essentially, a Warriordom -- a Masculinist and Warrior Culture in which the most important element of a Man's Life was his Warrior Manhood, his Fighting Spirit, expressed in competitive athletics -- and war.

Sokrates, too, saw significant military action, though, because he was older than Plato, in different battles.

But they are well attested to in the literature.

So -- famous Greeks, famous Athenians, like Sokrates, Plato, Aeschylus, etc -- as well as virtually all ordinary Greek Men -- lived through -- and participated in -- a lot of Combat -- Struggle -- Contest -- Battle -- War -- Fight.

BIBLION TETARTON

By Bill Weintraub

It wouldn't be surprising then, given their history and the reality of their day-to-day lives, if many Greeks -- indeed most of them -- believed that Fight is the Father of All.

And, in fact --

"Fight is the Father of All" is a saying attributed to the Greek philosopher Heraclitus, who died a few years before Sokrates was born, and so is known as a "pre-Socratic."

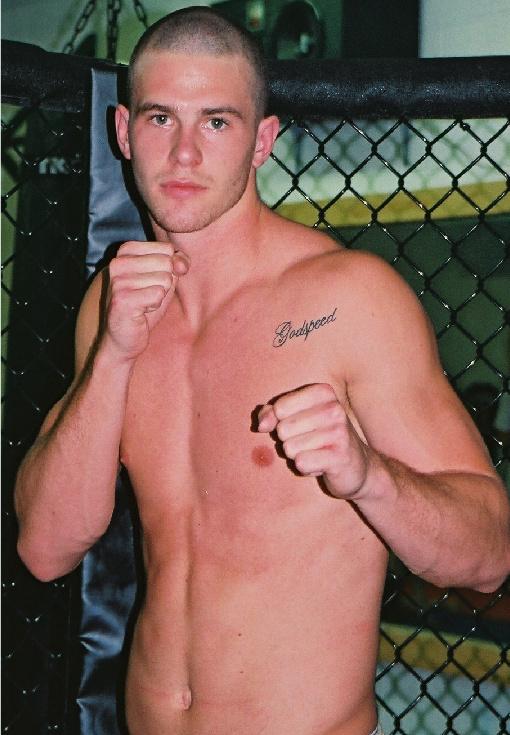

To fully understand that saying, and its meaning for our Lexicon of Manhood and our own Manly Lives, we can start by coming back to NW's phrase : "Aggression and the beauty of guys who asserted that aggression".

For NW, and for me, the Beauty of Guys -- a Beauty which is not just physical but moral also -- a Moral Beauty -- has always been tied to Aggression.

That is, to Fighting Manhood.

As it was for the Greeks.

For the Greeks, Moral Beauty and Fighting Manhood are inextricably intertwined.

And reductionally and functionally -- the same.

In ancient Greece, such Fighting Manhood was often expressed in fiercely competitive -- "agonal" -- nude male athletics.

As Erich Segal points out in his Foreward to Waldo Sweet's Sport and Recreation in Ancient Greece.

Segal, who died in 2010, is best known as the author of the saccharine Love Story.

But in real life he was a Harvard-educated classicist who taught at Yale.

In other words, a person of formidable erudition.

In his Foreward to Sweet's book, Segal notes that our word "sport" carries with it the sense of levity.

That's not true of the Greeks.

Their word, AGON, is the root of our word -- agony.

Which in Greek is agonia, and which means, first and foremost, a struggle for victory.

So an Agon is a Struggle, and the word Agon, says Segal, can "refer to encounters ranging from duels to debates."

Similarly, the Greek word athlos, from which we derive our word athletics, "could mean a contest taking place in a stadium or on a battlefield."

The idea of Fight as the Father of Everything permeated Greek life.

Segal:

So -- let's look more closely at Heraclitus and what he actually said.

First off, I first took the phrase "Fight is the father of everything" -- (which Segal expressed as "Strife is the father of everything") -- from Erich Segal's Foreward, and shortened it, and with good reason, as you'll see, to "Fight is the Father of All."

And as I said above, that phrase comes from the Greek philosopher Heraclitus, who was a pre-Socratic -- he died a few years before Sokrates was born, and his work has come down to us in fragments.

And not only do we have only fragments, but the fragments are gnomic at best and often just plain cryptic.

So it's always a bit of a stretch to figure out just what he's saying.

But his basic ideas are usually clear enough, as is his fundamental idea, that "all is in flux" -- thus his best known adage, 'You can't step in the same river twice.'

And that of course is describing what Plato, about 150 years later, would call the World of Becoming -- in which change is constant.

So -- Segal extracted the idea that "Strife is the father of everything" from a fragment which I tracked down to this website

-- and which, thankfully, has the Greek alongside it.

And there I found not one, but two fragments from Heraclitus which are relevant and more than relevant to our Manly Lexicon -- and to our Manly Lives.

The first is "Fragment 53," and it begins with an ancient Greek word -- Polemos -- which the site translates as "War."

That's technically accurate but -- to the people of our time -- somewhat misleading.

So -- let's start by looking at the definition of

We see that Polemos -- one of the most important words in the Greek language -- can be translated as battle, fight, war.

And that war is actually third in the list.

Which is why I frequently say that Ares is the God of Fight.

Because all of the Greek words variously translated as contest, conflict, struggle, strife, war, battle, combat, etc -- words like and including Agon αγων, Athlos αθλος, Eris ερις, Hamilla αμιλλα, Mache μαχη, Polemos πολεμος, Neikos νεικος, etc -- reduce -- to FIGHT.

Mache is defined as battle, FIGHT, combat.

Neikos is defined as strife, battle, FIGHT.

Polemos is defined as battle, FIGHT, war.

FIGHT.

Sometimes the Fight is unarmed ; and sometimes it's with weapons.

Sometimes the Fight is between masses of Men ; and sometimes it's one-on-one.

But it's always Fight and it's always about Fight.

Fight is the agonal principle and agonistic imperative.

Fight is the Father of All and King of All:

Fight is the Father of All and the King of All; and some He has made Gods and some Men, some bond [slave] and some Free.

Πολεμος παντων με&nu πατηρ εστι, παντων δε Βασιλευς, και τους μεν Θεους εδειξε τους δε ανθρωπους, τους μεν δουλους εποιηδε τους δε ελευθερους

~Heraclitus, Fragment 53, translated by Burnet.

"Fragment 53" is a profound statement by Heraclitus, with profound spiritual significance.

Because, and this is just for starters, it links Heraclitus (ca. 540 - 475 BC) -- who died about 50 years before Plato (ca. 427 - 348 BC) was born -- first with Plato himself, and then with Platonist and then Neo-Platonist philosophy as it developed between the death of Plato in 348 BC and the death of the great and Hellenizing Emperor Julian in 363 AD.

Specifically, Fragment 53 links Heraclitus with Plato's Idea of Good.

Because, of course, if Fight is the Father of All and King of All -- it takes on the universal attributes not only of what Plato would later call the World of Being -- but of the Idea of Good, the highest good, the Supreme Good -- itself.

So -- we're going to look at that -- and more.

But first, we need to consider another of Heraclitus' gnomic pronouncements -- which is today known as "Fragment 80":

Burnet translates that as "We must know that war is common to all and strife is justice, and that all things come into being through strife."

But actually Heraclitus doesn't say, strife is justice -- he says justice is strife -- which is more radical.

Heraclitus:

Fight is common to All, Justice is Strife, and Everything comes into being -- be-comes -- in accordance with Strife.

Let's break that down:

We know that, and we know particularly that Fight and Fighting Spirit are common to All Men.

To the Greeks, that's correct.

Think of Xenophon's Strife of Valour -- his Struggle of, for, and about Manhood -- which we discussed in, among other places, the Prologue to Biblion Proton.

To Xenophon, that Struggle brings about and preserves the Justice -- the Eunomia and Homonoia -- the Manly Moral Order and Warrior Concord -- which constitute the Spartan state.

Justice is Strife ; Strife is Justice.

Everything becomes -- Heraclitus is talking about the realm of the senses, the World of Flux --

In accordance with Strife -- Struggle, Strife, Combat, War, Fight.

Strife, Struggle, Combat, War, Fight, then, is the Model -- the

Strife, Struggle, Combat, War, Fight, then, is the Model -- the Paradeigma -- in my reading of Heraclitus -- which shapes everything -- in what Plato would later call the World of Becoming.

And Plato further refined that formulation to say that what we sense, what we experience, in the World of Becoming are shadows, copies, and reflections of the Ideal Forms in the World of Being.

Which means that --

Everything comes into being -- becomes -- in accordance with Strife.

Which, then, must be -- an Ideal Form, an Essence.

What, then, is Strife?

Is Strife -- Fighting Manhood?

Yes, and without question.

For --

In the human realms of both Becoming and Being, Strife is what we saw it to be in the Prologue to Biblion Proton of this Lexicon:

Strife is the Struggle, the Fight, between two Fighting Men, the Struggle of, for, and about Manhood.

Put more simply:

Strife is Fighting Manhood -- Fighting -- Fighting Manhood.

Fighting Manhood Against Fighting Manhood.

In the human sphere, Strife is the Struggle of Manhood Against Manhood.

The Fight of Manhood Against Manhood.

Strife is the Fight -- the ManFight -- *itself* -- the Struggle, the Combat, of Fighting Manhood Against Fighting Manhood.

Whose goal is to Perfect Manhood.

As Jaeger says:

Again -- think back to Xenophon's Strife of Valour -- which is really a Struggle of, for, and about Manhood.

What Marchant calls a Strife of Valour is really a Struggle between and among Young Fighting Men, a Fight of Manhood, a Fight for Manhood, a Fight about Manhood.

So -- in the sensible realm, the World of Becoming, Strife is Man Against Man.

And that Struggle and Strife of Man Against Man takes place within, between, and among the Warriordoms of the World of Becoming.

As Heraclitus says:

Everything becomes in accordance with Strife.

Including Man, who becomes Man in the Strife of Man Against Man.

Think back to the Prolegomena, and the story of Aristonicus the Harp-Player.

He became a Man in the Strife of Man Against Man.

By Fighting, Aristonicus left his old state of being, harp-player, and came, says Arrian, into a new state of being:

Man.

Aristonicus "was killed -- having fought however not like a harpist, but like a man."

In the original Greek, the verb Arrian uses is "gignomai" -- γιγνομαι -- which means -- "come into a new state of being."

The translator, de Selincourt, says "having fought however not like a harpist, but like a man."

But, what Arrian is really saying is that by Fighting, Aristonicus left the state of "harp-player," and came into a new state of being -- that of Man.

That of Brave, Good, and Noble -- Man.

And that's certainly how the Greeks saw it:

Fighting Makes the Man.

It Awakens the Man, as we often say in the Alliance, to his Manhood.

Fighting Awakens the Man to, it helps him UN-forget, his Manhood.

Manhood.

Which is the Willingness and Ability to Fight.

So -- in the Warriordom and Warriordoms, Man becomes Man -- Man can only become Man -- in the Struggle and Strife of Man Against Man.

Yet, and that said --

What's really going on -- is the Struggle and Strife -- the Fight -- of Manhood Against Manhood.

And that Manhood, that Fighting Manhood, ultimately resides, as we've seen, in the Warrior World of Being.

The Warrior Kosmos.

And because that Fighting Manhood resides in the Warrior World of Being, the Warrior Kosmos, where it is, de facto, the Idea of Good, it's both the Primal Love -- see Biblion Deuteron -- and the Primal Cause -- of the Warrior All:

from Proton πρωτος = first, primal; and

Aitia αιτια = cause [Roman numeral II], Lat. causa = cause, reason

Functionally, the Proten Aitian is identical to the Proton Philon -- the Primal Love -- which is the Idea of Good, the Supreme Good:

η πρωτη αιτια = he prote aitia = the first cause

In Heraclitus' formulation, Polemos πολεμος -- Fight -- is the First and Primal Cause:

Making Fight -- again, functionally -- the Idea of Good, the Supreme Good.

(πρωτην αιτιαν = proten aitian = First Cause, Primal Cause -- FIGHT is the Father of All and King of All -- FIGHT is the Primal Cause, the Idea of Good, the Supreme Good.)

Plato uses the phrase

αριστος των αιτιων = aristos ton aition = best, noblest, bravest, finest, morally best, and, therefore, Most Manly -- of causes.

The First and Primal Cause is then the best, noblest, and bravest -- and, remember, aristos is one of our ARES words -- it's rooted in the First Notion of Goodness -- Fighting Manhood :

~Liddell and Scott, 1909

We see then that aristos is defined as "bravest, noblest," and "morally finest" -- ALL of which mean and reduce to most Manly -- which in turn means that:

The First Cause and Primal Cause is the most Manly -- of causes.

And Manliness of course is a function and expression of Fighting Manhood.

Translation:

The First and Primal Cause is Fighting Manhood.

Plato also says

~Plat. Tim. 28c, translated by Bury.

The word Plato uses for Universe is "All" = pantos = πας = all -- the same word that Heraclitus uses for All = pantos = πας = all.

So: what Plato actually says is "to discover the Maker and Father of All were a task indeed; and having discovered Him, to declare Him to All were a thing impossible."

While Heraclitus says, "Fight is the Father of All and King of All."

Heraclitus:

Fight is the Father of All -- all the Kosmos -- and King of All -- all Men.

Plato:

To discover the Maker and Father of All -- all the Kosmos -- were a task indeed; and having discovered Him, to declare Him to All -- all Men -- were a thing impossible.

There's a great symmetry between what these two great thinkers have said.

Again, there's a great symmetry -- an intense congruence -- between what these Men have said.

Which means, and, for the third time, functionally, that Plato and Heraclitus, though separated by perhaps a hundred years, are saying essentially the same thing:

Fight is Father and King -- the Primal Cause -- of All ;

Fighting Manhood is Father and Maker -- the Primal Cause -- of All.

So:

When we make the leap from Fight is the Father of All --

To Fighting Manhood is the Father of All --

What we're saying is that Fight and Fighting Manhood -- are synonymous.

Which they clearly are.

Fight -- and Fighting Manhood -- are synonymous.

Fight and Fighting Manhood are synonymous.

The Hallmark of Manliness -- the Hallmark of Manhood -- is, as my foreign friend says, Fighting Spirit.

Fighting Spirit.

Fighting Manhood.

Which is, according to Liddell and Scott's Greek-English Lexicon, the First Notion of Goodness.

And which, according to Lewis and Short's Latin Dictionary, is :

MANHOOD --

By which Lewis and Short mean Fighting Manhood --

Is the Sum of All the Corporeal and Mental Excellences of Man.

Fighting Manhood is the Sum of All the Excellences of Man.

That definition dates from 1879.

And it tells us what MEN have believed and known to be True for literally tens of thousands of years:

That Fighting Manhood is the sum of all the corporeal and mental -- which includes the moral and spiritual -- excellences -- of Man.

And it's what guys like me and NW have said on our own -- for years:

That Fighting perfects the Male Body -- that's the corporeal part -- because that's what the Male Body was designed to do -- to FIGHT ;

And -- as we've seen throughout this Lexicon -- that Fighting Manhood defines mental and above all moral and spiritual excellence as well.

So -- Lewis and Short give a list:

strength, vigor; bravery, courage; aptness, capacity; worth, excellence, virtue

That's what Fighting Manhood is:

Strength.

Vigor.

Bravery.

Courage.

Aptness.

Capacity.

Worth.

Excellence.

Virtue.

Fighting Manhood is the Sum of All the Excellences of Man:

And yet, ALL OUR LIVES Fighting Manhood has been denigrated and marginalized.

While the societal structures -- in places like ancient Greece -- which supported it and gave it its True and Manly form -- have been destroyed.

That's the problem.

And Men's Lives will never again be Right and Whole -- until that problem has been corrected.

And this statement has, once again, been acknowledged to be True:

Now:

Regarding Heraclitus' and Plato's formulations -- and what I said above about the great symmetry and intense congruence between them --

Fight is Father and King -- the Primal Cause -- of All ;

Fighting Manhood is Father and Maker -- the Primal Cause -- of All

That great symmetry and intense congruence is there because, as the Prolegomena and Biblion Proton make clear, there's both an intense culturally-mandated connection and an equally intense and essentially spiritual identification between and among Men, Fighting, Fighting Manhood, and what Plato calls the Idea of Good -- that is, Goodness, the Supreme Good, the Sanction, Virtue, Righteousness, Excellence, Moral Beauty, Moral Order -- and Manly Worth.

And if you've read the Prolegomena and Biblion Proton carefully and thoroughly, and then Biblion Deuteron and Triton -- you know what I've said is NOT a stretch.

To the contrary.

Couldn't be clearer.

Because this is the way these Men -- that is, Men like Plato and Heraclitus, and, for that matter, Xenophon -- a far less exalted thinker --

It's the way these Men, Men who lived in a Masculinist, Warrior Culture -- a Warriordom -- and whose ideas and ideals were shaped by a Warrior Kosmos, a Warrior World of Being -- thought.

It's the way they thought:

Manhood -- The First Notion of Goodness -- say Scott and Liddell ;

Manhood -- The Sum of All the Excellences of Man -- say Lewis and Short.

Those four Men were 19th-century classicists, highly regarded in their field, steeped in the books and the society they were studying, and still living in a predominately Masculinist and to a large degree Warrior -- Culture.

And that's how they defined Manhood -- Fighting -- and Fighting Manhood.

As The First Notion of Goodness ; and

The Sum of All the Excellences of Man.

And that understanding of Fighting Manhood as the First Notion of Goodness and the Sum of All the Excellences of Man -- is within the language and the way it's used.

Take, for example, this statement by Plato, in the Republic, regarding nude athletics:

I do.

But when, I take it, experience showed that it is better [agathos] to strip [apoduo] than to veil all things of this sort, then the laughter of the eyes faded away before that which reason [logos] revealed to be best [aristos], and this made it plain that he talks idly who deems anything else ridiculous but evil [kakos], and who tries to raise a laugh by looking to any other pattern of absurdity than that of folly and wrong [kakia] or sets up any other standard of the beautiful [to kalon] as a mark for his seriousness than the good [to agathon].

~Plat. Rep. 5.452d, translated by Shorey.

But when, I take it,

experience showed that it is better to strip than to veil all things

of this sort

"it is better to strip than to veil all things of this sort"

That's unequivocal, isn't it?

The word Plato uses for "strip" is apoduo -- meaning strip off, strip naked, strip for the palaistra, etc. -- and it's quite common in ancient Greek literature.

Guys are constantly stripping, and with little provocation.

They just like taking off their clothes.

Because, clearly, to be "unclad" is to be Manly.

For example, when the reforming Spartan king Agis proposed restoring Sparta to her old way of austerity and equality, Plutarch tells us,

They stripped to show their mettle -- their mettle, their Manliness.

It's a great phrase, and a great scene.

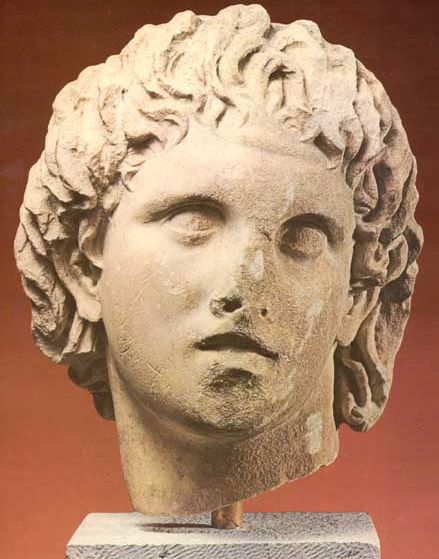

As is the moment when Alexander says to his assembled army, Come now, strip naked and show me your wounds, and I'll show you mine.

And you have to imagine Alexander stripping naked before his Men, and his Men stripping naked before him, so that all may show off their wounds, which are, as we discussed in Biblion Proton, Badges and Ikons -- Badges of Manliness, Ikons of Manhood.

Fighting Manhood.

And Plato, who preceded both Alexander and Agis, legitimates, in his philosophy, that already core Greek idea -- that Male Nudity is Manly, Manlier, Manliest -- by saying, "it's better to strip than to veil."

And the word Plato uses for "better" is the comparative of agathos, which is the adjectival form of the noun areté -- Manhood, manly excellence, manly goodness ; and that comparative form of the word can also mean not only stronger and braver -- but, most importantly, more Manly.

So what Plato is saying is that "it's better, it's stronger and braver, it's more excellent, it's more Manly, to strip than to veil all things of this sort."

It's more Manly -- to strip -- than to veil.

And then Plato says, "the laughter of the eyes faded away before that which reason revealed to be best"

And the word for best is Aristos -- which, like areté, derives from Ares:

~Liddell and Scott, 1889.

Look at it, guys, look at the definition's juxtaposition of the words Aristos and Ares, because it's just sitting there, that linkage between Aristos and Ares, between Best and Fight, between Most Manly and Fight -- it's just sitting there, plain for you and the rest of the world to see:

αριστος Αρης

Best derives from Fight, Aristos comes from Ares -- that's what Liddell and Scott are saying.

Just as -- and as we discussed in the Prolegomena, and in Biblion Proton *and* Biblion Deuteron:

Manhood is rooted in and flows from Fight, areté -- Manly Excellence -- is rooted in and flows from Ares -- the God of Fighting Manhood.

I wonder how many times I'd have to say it for you to believe it.

Too many, I expect, even though it's right there for you to see with your own eyes:

Those are links.

Click on the links and you'll see it:

But you won't.

You won't see it because you don't want to see it.

You're afraid to see it.

You're afraid.

Nevertheless, and despite your fear, which has continually, throughout your lives, and continues to, UN-man you -- Aristos means not only "best" but also "noblest" and "bravest" -- that is,

Most Manly.

So -- to the Greeks --

It's stronger and braver -- it's More Manly -- to strip -- than to veil.

And Reason reveals such Male Nudity to be Aristos -- not just Noblest and Bravest, but, most importantly, Most Manly.

Reason reveals Male Nudity -- in Fight Sport and in War -- to be Most Manly.

Male Nudity is Most Manly -- it is Manlier to be Nude -- than to be clad.

Which is why the MALE GODS, including ARES Himself, are usually depicted as NUDE MEN.

And what is it which tells us that Naked Truth and Nude Combat is stronger and braver and above all More Manly than the veils of opinion and lies?

REASON.

And Greek nouns have gender and Logos, as it happens, is Masculine.

Reason is Manly.

(See Sexual Freedom.)

Reason tells us, Reason reveals, what is Best:

[μηνυω = menuo = to disclose what is secret, reveal, betray, generally, to make known, declare, indicate]

"reason [logos] revealed to be best [aristos]"

Reason -- Manly Reason, Manly Rationality -- reveals that Male Nudity -- which is also Male Truth -- is Best -- Most Manly.

Manly Reason tells us -- Men -- what is most Manly.

And what is Most Manly?

To be a Man -- Fighting another Man -- Nude.

Plato:

Assholes -- the opinionated slackers of the world of becoming -- who can't think or reason, but can only talk -- "idly" -- those assholes will claim that male nudity is bad or silly or ridiculous.

But they're full of shit --

Only evil [kakia] is ridiculous.

So the only standard for the Beautiful -- To Kalon -- is the Good -- To Agathon.

Male Nudity -- particularly in Fight Sport because that's what Plato's talking about when he says gymnasion / nude athletics -- is both Beautiful -- Morally Beautiful -- and Good.

AND -- and it's an important "and" -- those who talk "idly" and "try to raise a laugh" about male nudity -- are supporting evil.

And the word Plato uses for evil is kakos -- which derives from kakke = shit.

While the word for Beautiful is Kalos = noble and beautiful.

And we're back to the Spartan Ta Kala -- The Noble Warrior Way of Manly Moral Beauty --

And Plato's word for Good is Agathos, which is the adjectival form of Areté -- Manhood, Manliness, Manly Excellence, Manly Goodness, Virtue.

So --

But when experience showed that it's more manly to strip than to veil all things of this sort -- that is, the male genitals -- then the laughter of the eyes faded away before that which reason, which is itself manly, revealed to be most manly ;

and this made it plain that he talks idly who deems anything else ridiculous but evil, which of its nature is excremental, and who tries to raise a laugh by looking to any other pattern of absurdity than that of folly and wrong or sets up any other standard of the Morally and Manfully Beautiful as a mark for his seriousness than the Good -- which is Manhood.

That's what Plato is saying because that's what the words he uses -- mean.

Because it's what they reduce to by virtue -- of what they're rooted in:

Manliness and Manhood.

Which in turn are rooted in and flow from ARES -- the God of Fighting Manhood.

That's who Ares is.

Sokrates says so:

~Plat. Crat. 407d, translated by Fowler.

"Ares would be named for his Virility and Manhood, and for his Hard and Unbending, Muscular and Phallic, nature."

Virility and Manhood, Hard and Unbending, Muscular and Phallic.

Thus Sokrates.

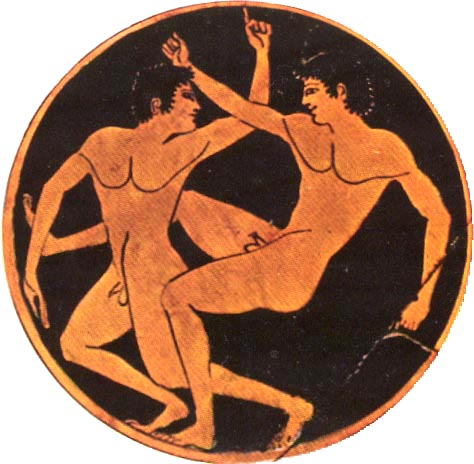

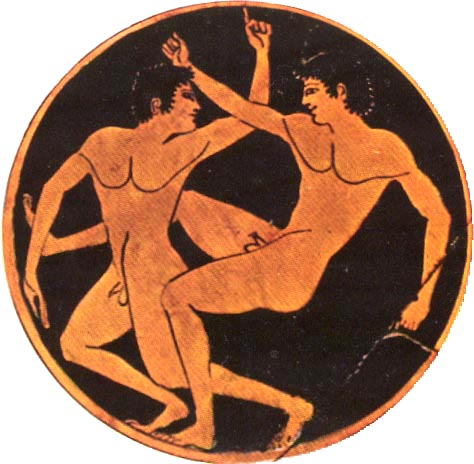

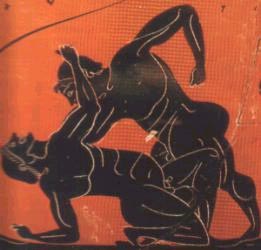

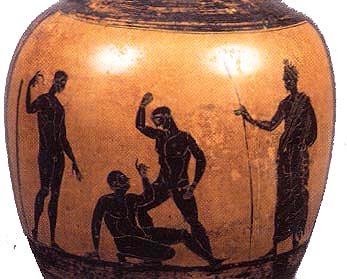

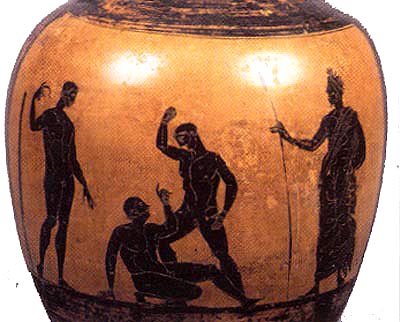

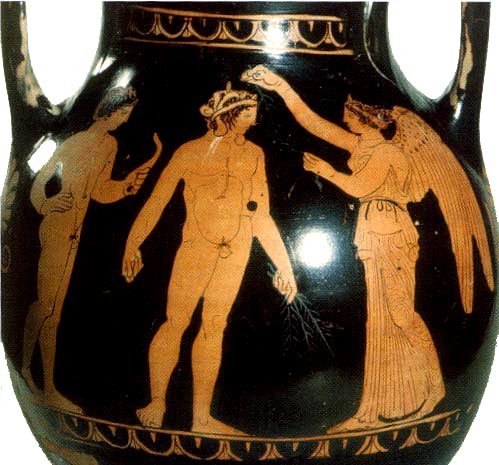

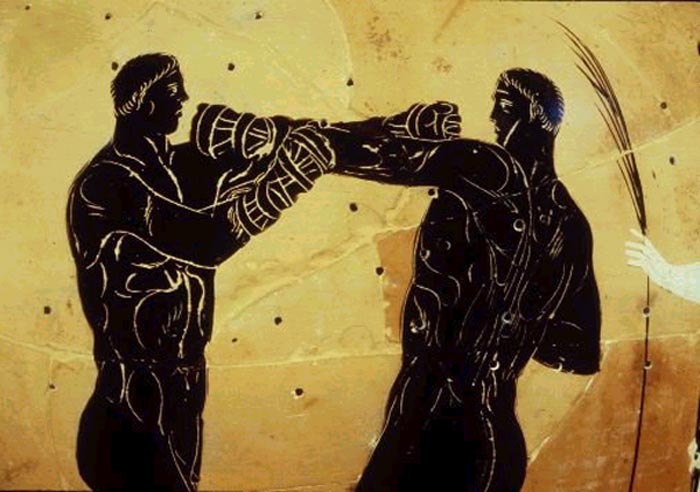

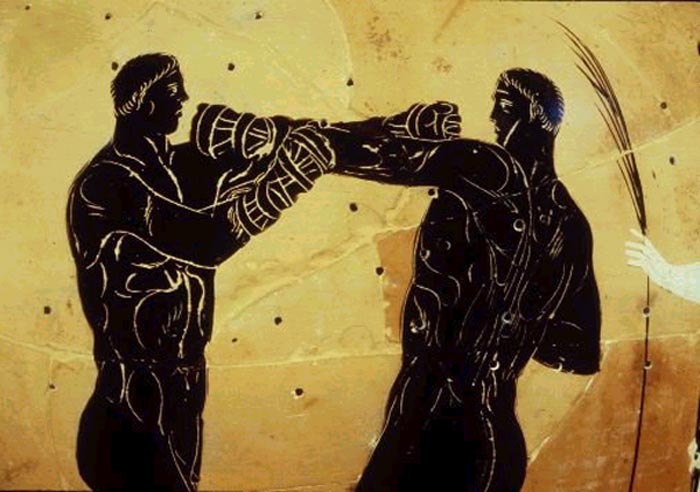

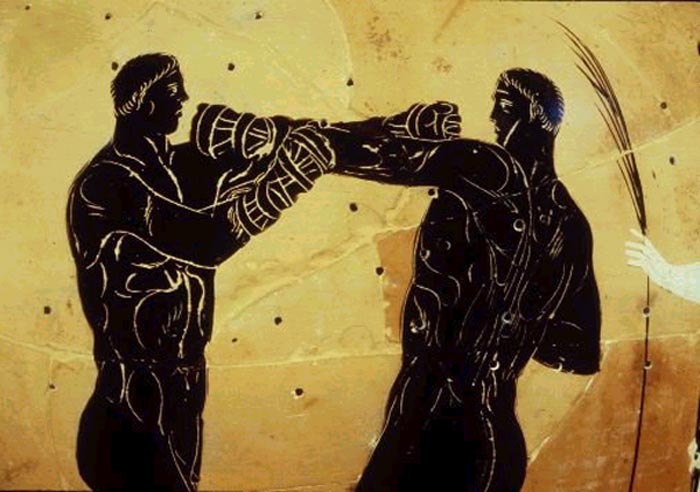

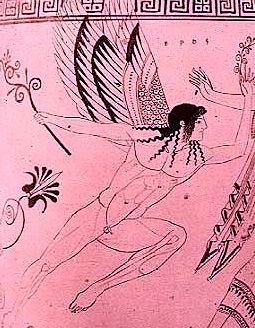

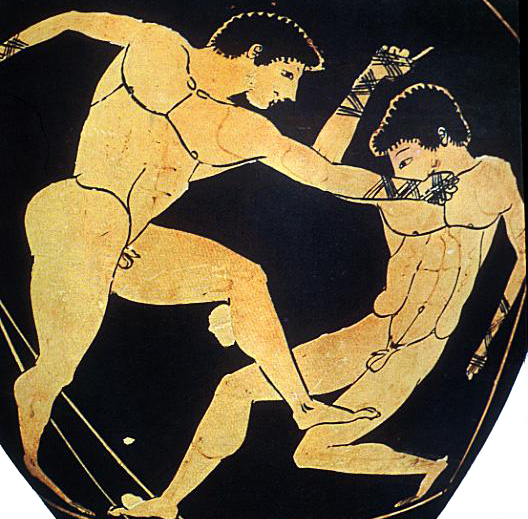

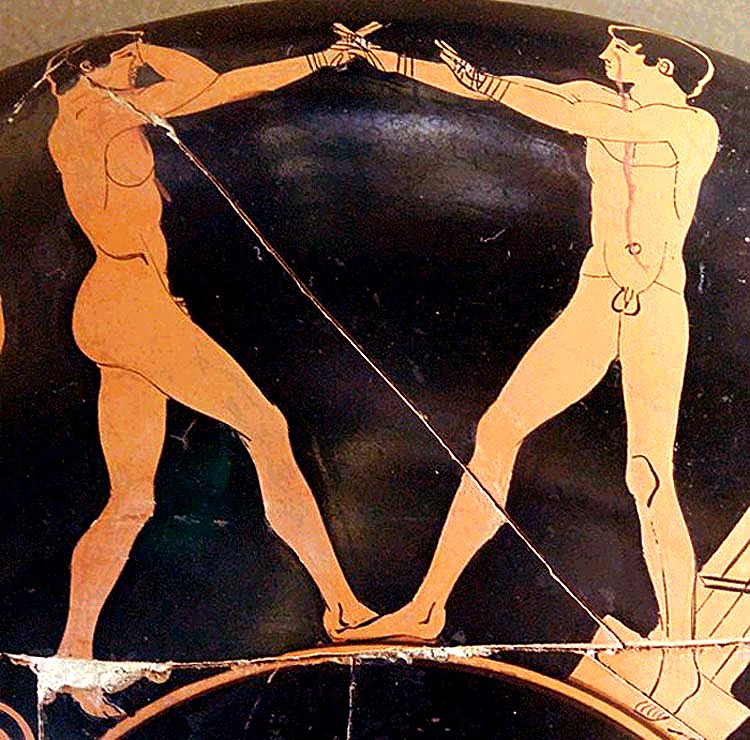

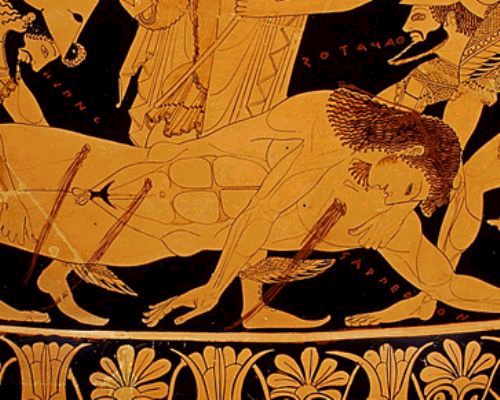

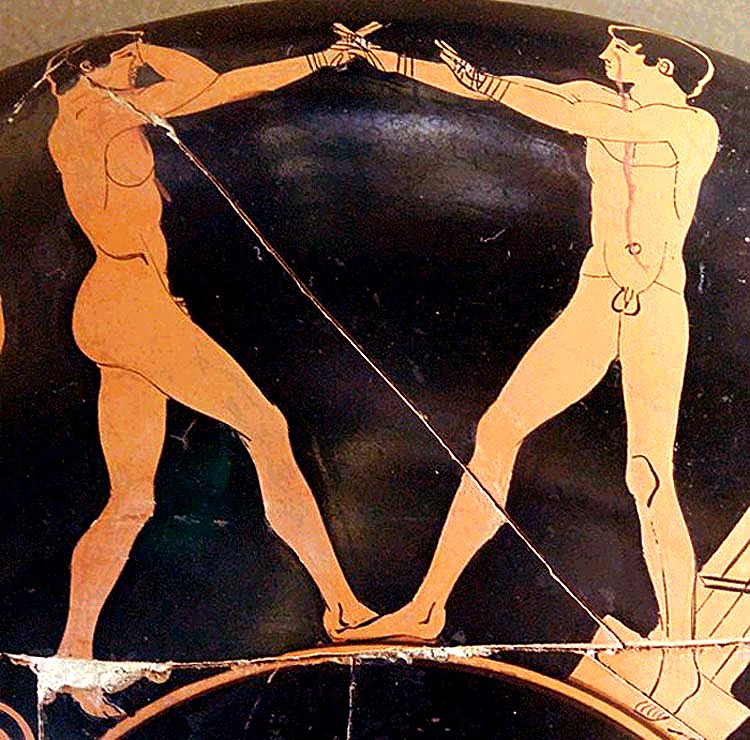

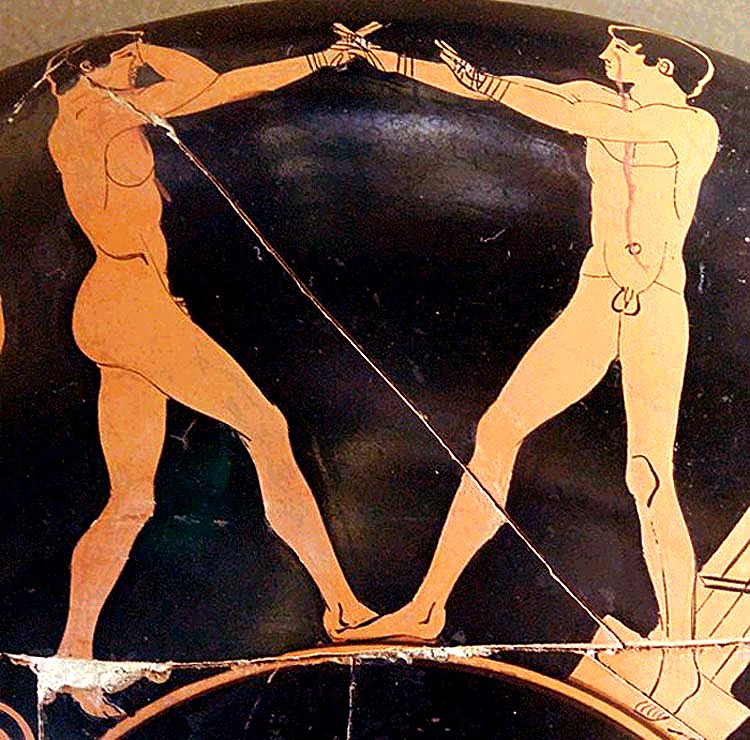

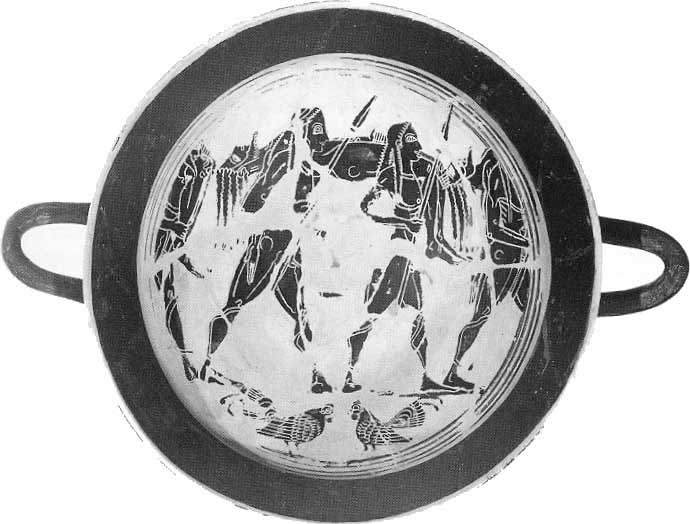

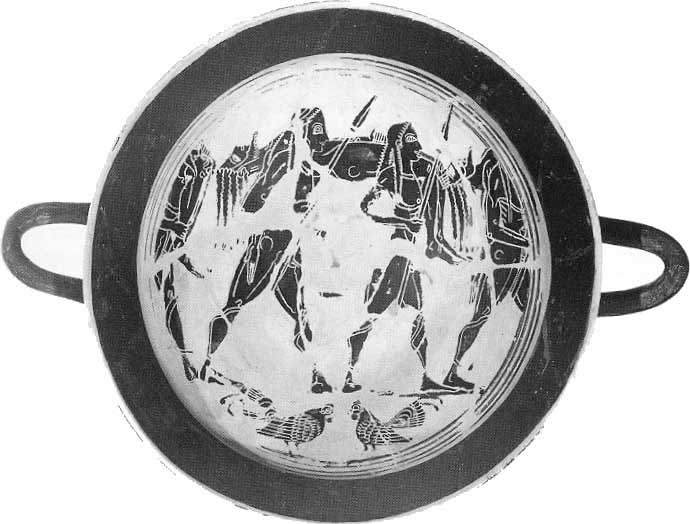

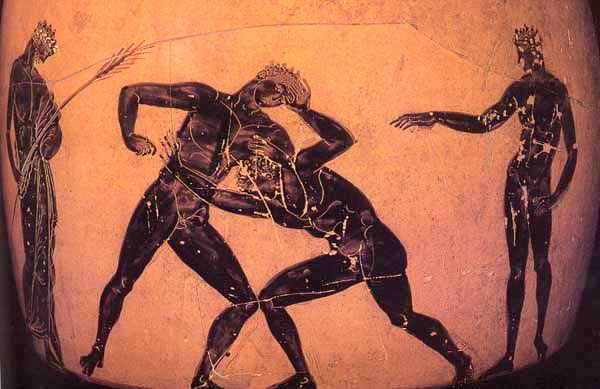

Which is no doubt why the male genitals are displayed -- in combat:

It's better to strip than to veil -- because it's more Manly.

And Reason -- Logos -- which is itself Manly -- reveals -- that such stripping, such open display of the male genitals both in war and in what we today call "sport," but which is actually agonia -- one man's strenuous physical effort to overcome another -- is most Manly.

To say otherwise is to talk idly.

And it's wrong to do that.

It's wrong to set up any other standard of the Beautiful -- than the Good.

The Good -- which is Manhood, Fighting Manhood, originates in and devolves from Manly action, action taken in and during Combat.

The Beautiful is Moral Beauty -- and because the standard for the Beautiful is the Good -- Moral Beauty too must originate in and devolve from Manly action, action taken in and during Combat.

And in our discussion of Kalon and Ta Kala in Biblion Proton, I've given you examples of that.

Eg: Anaxibios, the Spartan commander, and his Lover, choosing to preserve eutaxia, good discipline, and die at their posts.

That's a Kalon -- a Morally Beautiful deed -- and its Moral Beauty derives from its relationship to the Good.

Such Good is called Manhood.

And it's the Supreme Good.

Which is why Liddell and Scott say that Manhood is the First Notion of Goodness ;

and Lewis and Short say that Manhood is the Sum of All the Excellences of Man.

And when they say Manhood -- they mean FIGHTING Manhood.

They mean Fighting.

So:

It's critical that you understand that both morally and spiritually and therefore "kosmically" -- that is, in terms of the Warrior Kosmos -- Fighting Manhood functions as and reduces to Fight ; and Fight functions as and reduces to Fighting Manhood.

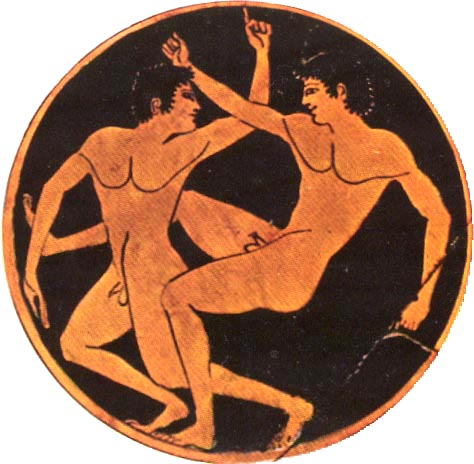

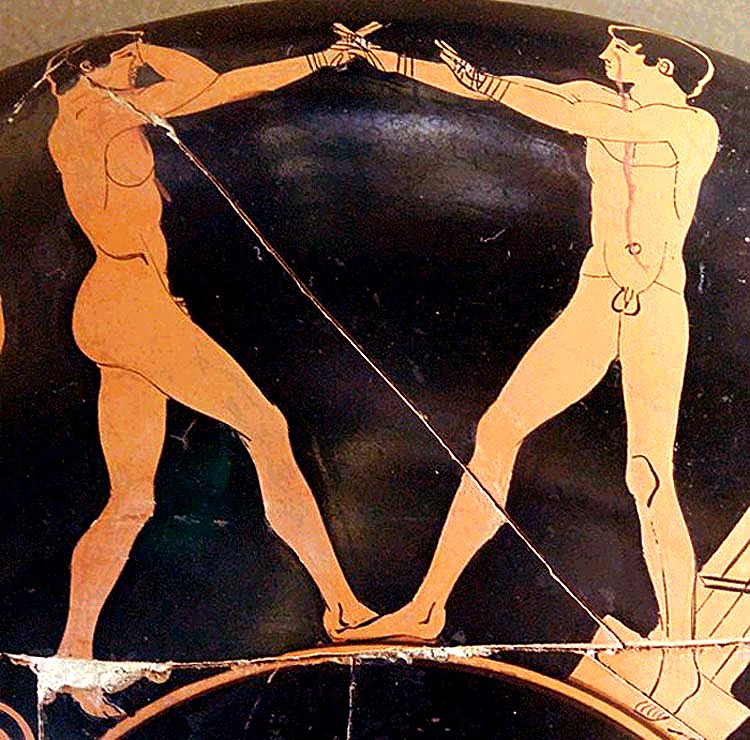

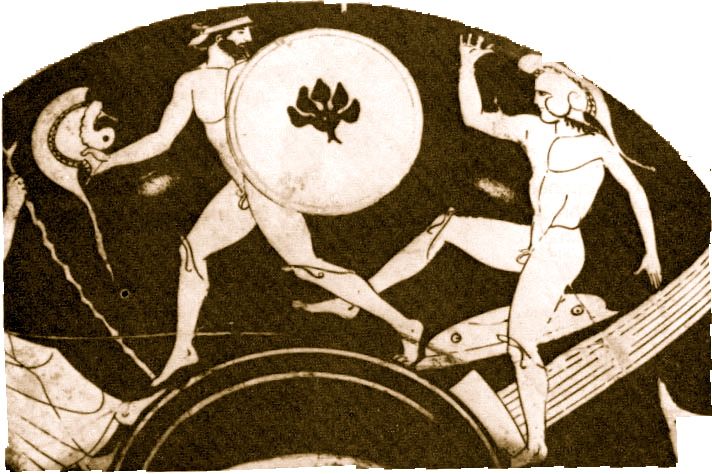

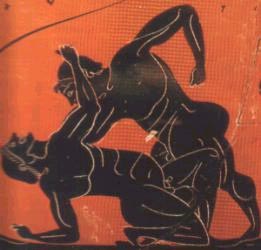

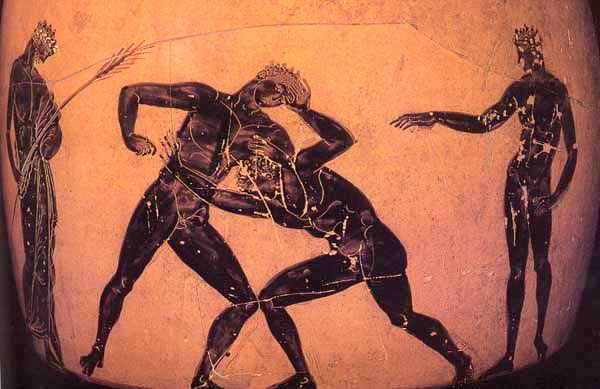

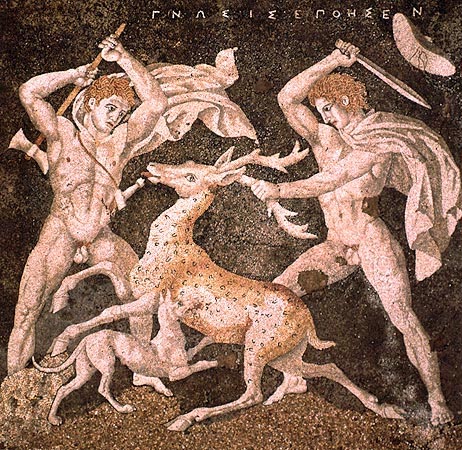

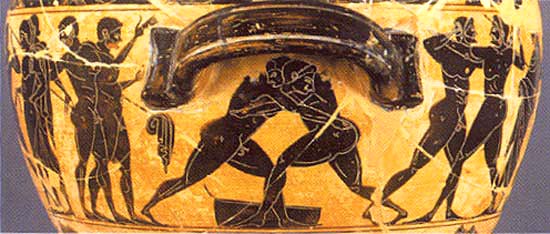

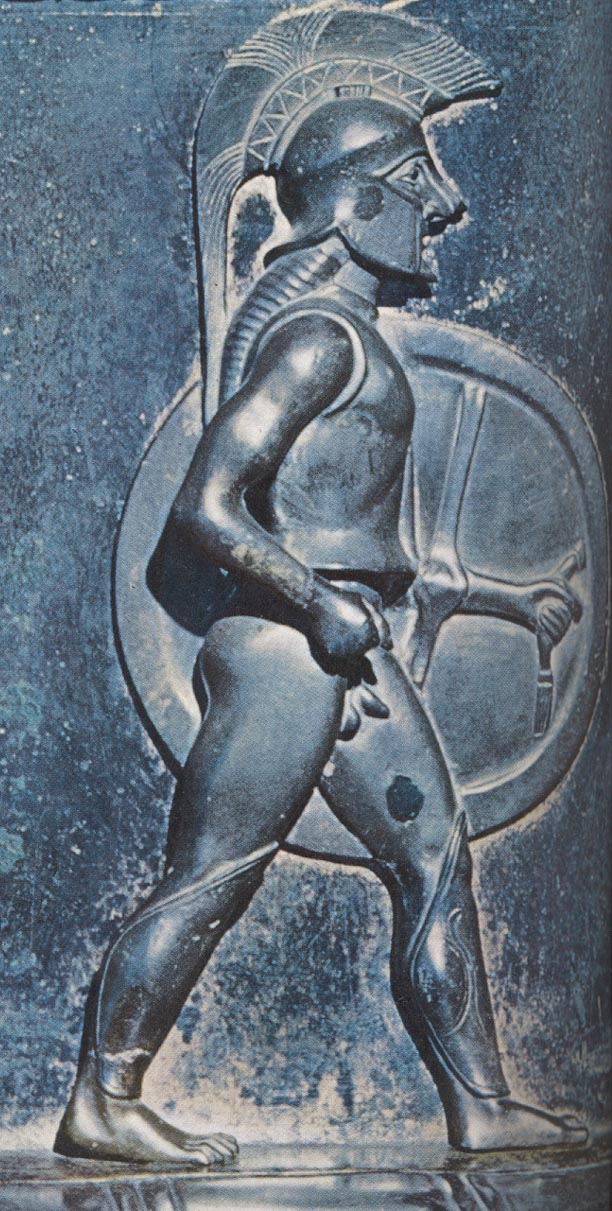

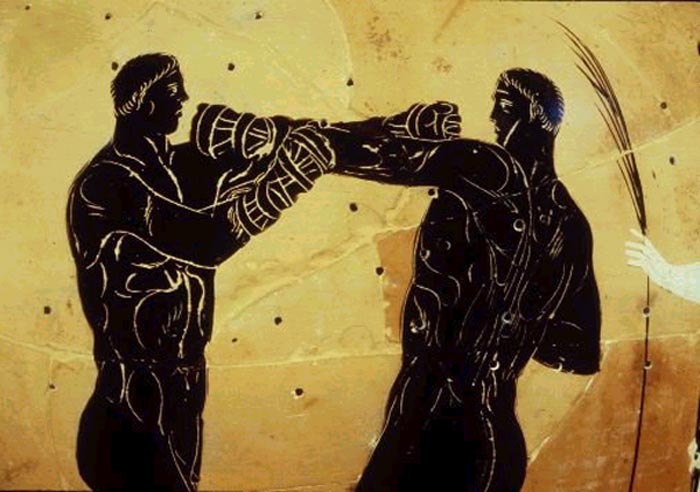

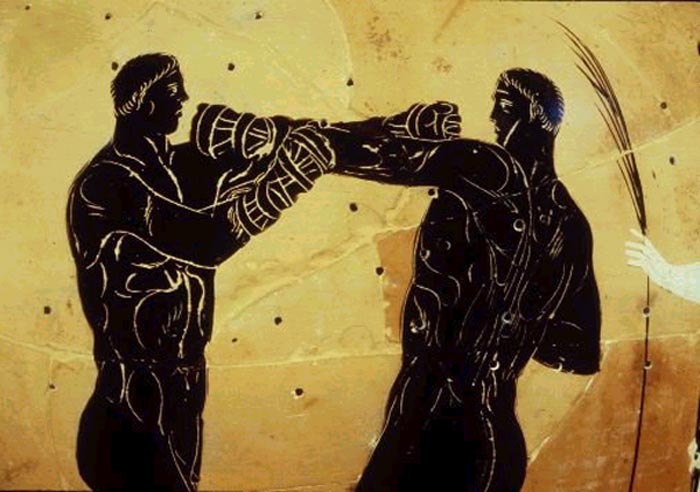

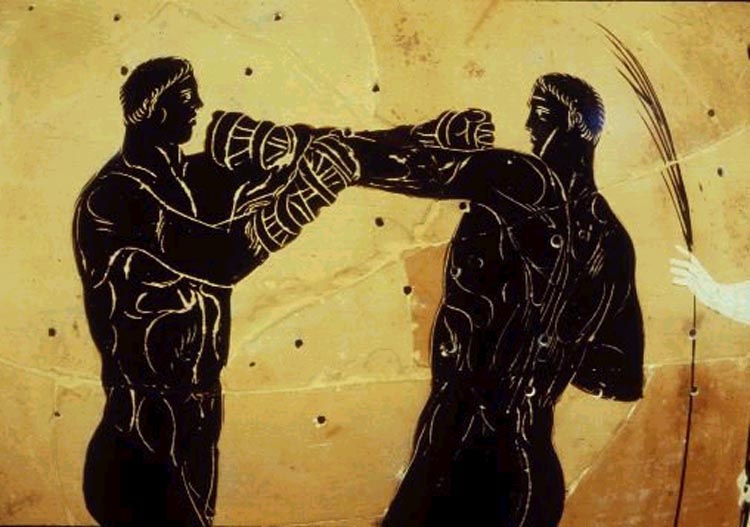

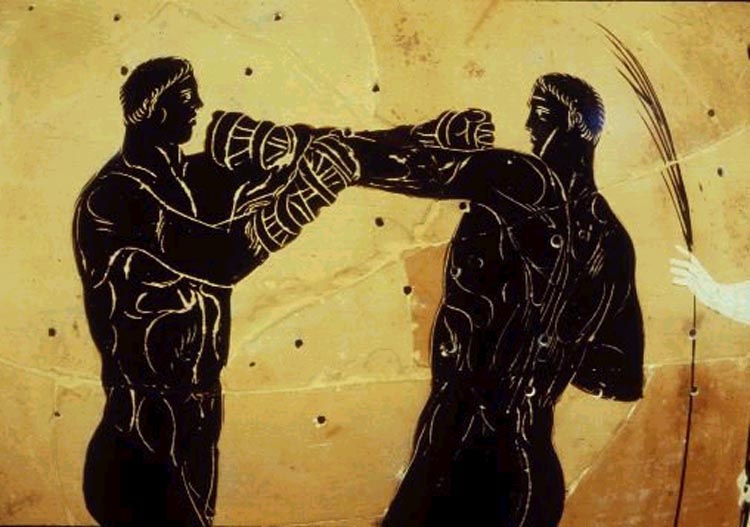

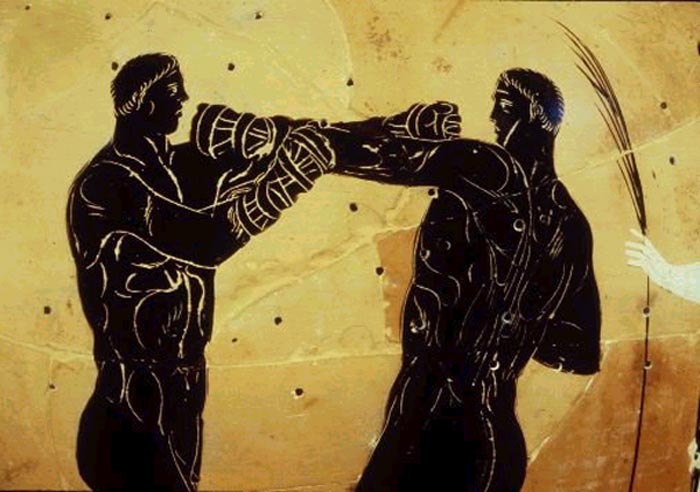

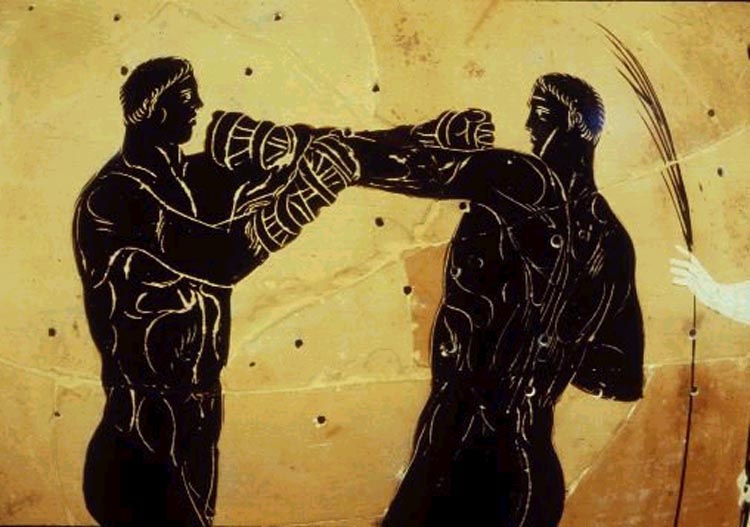

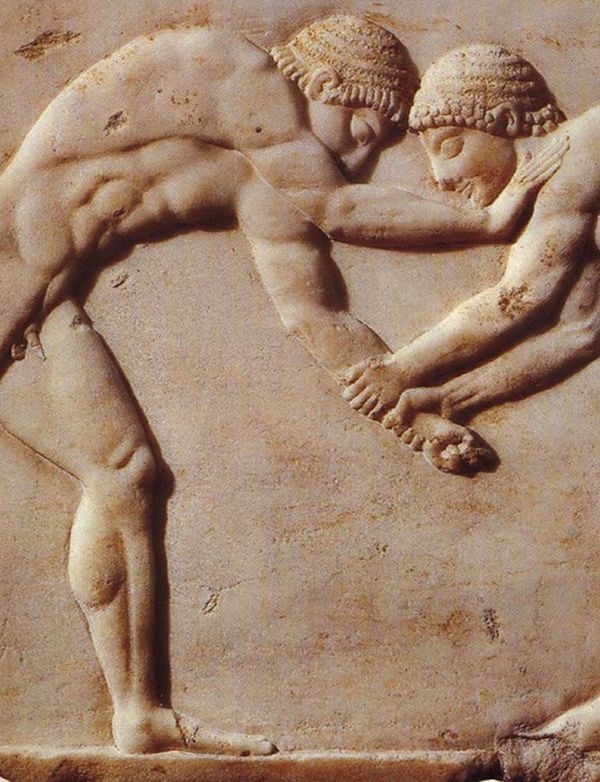

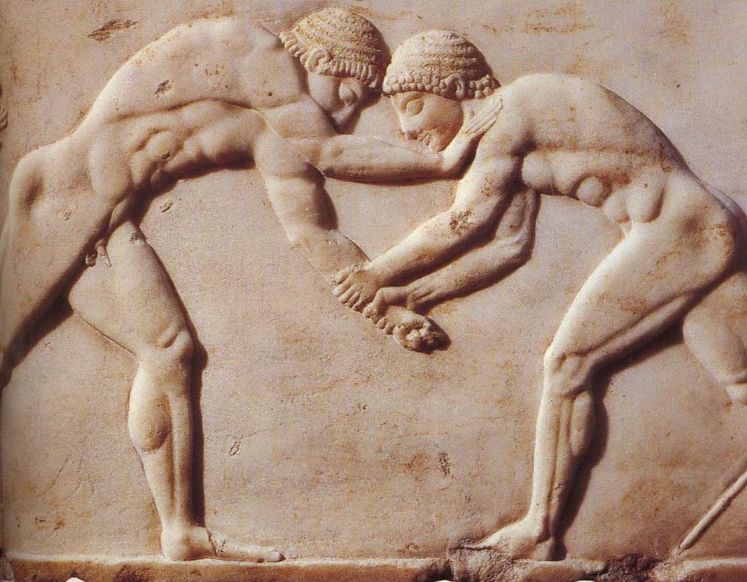

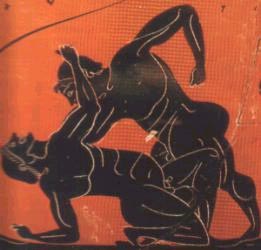

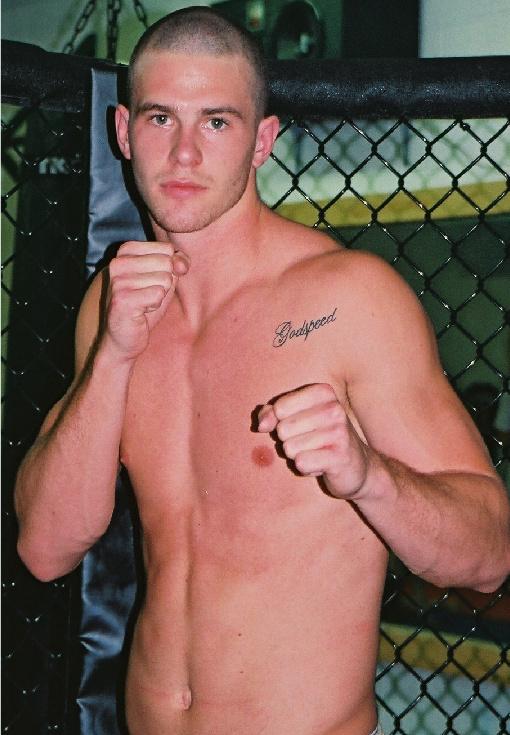

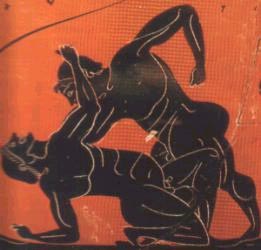

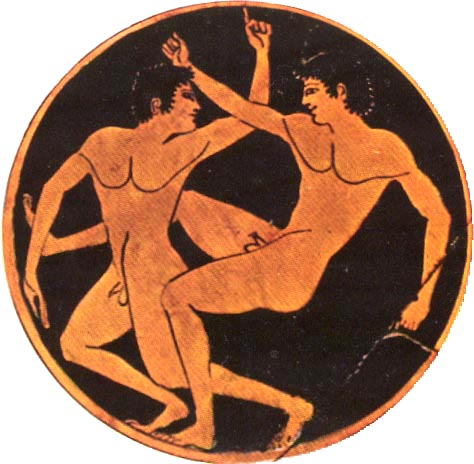

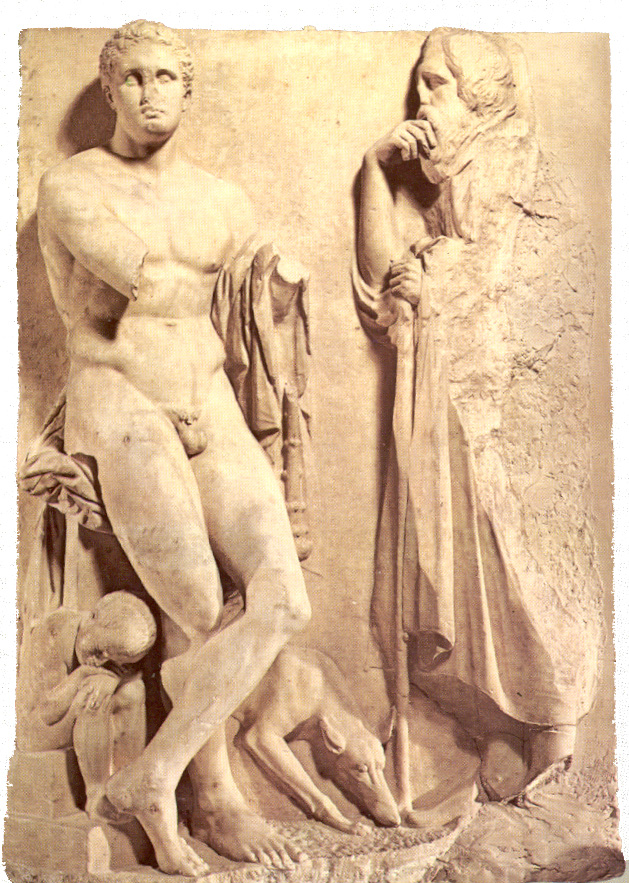

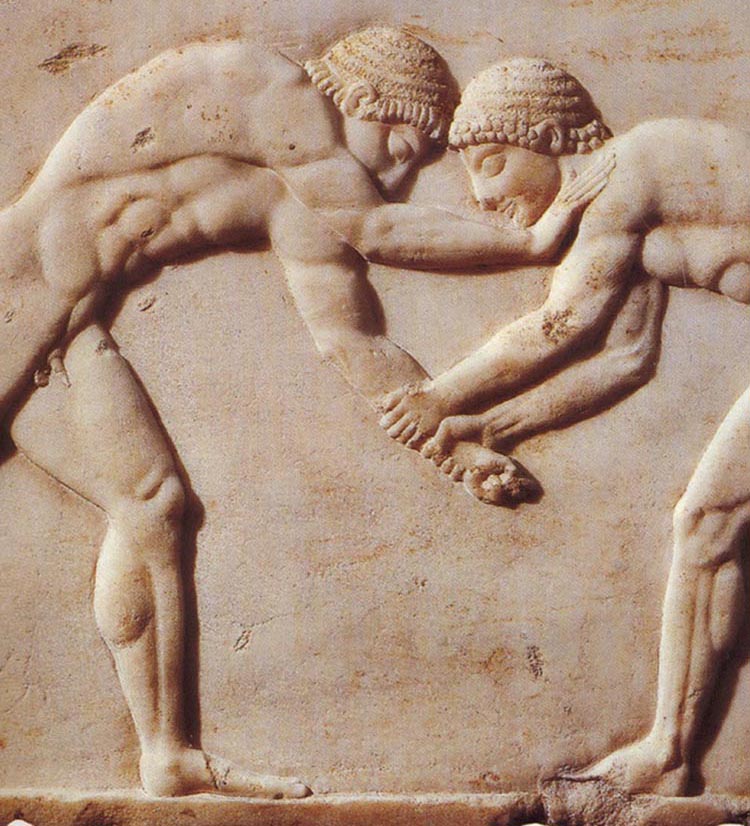

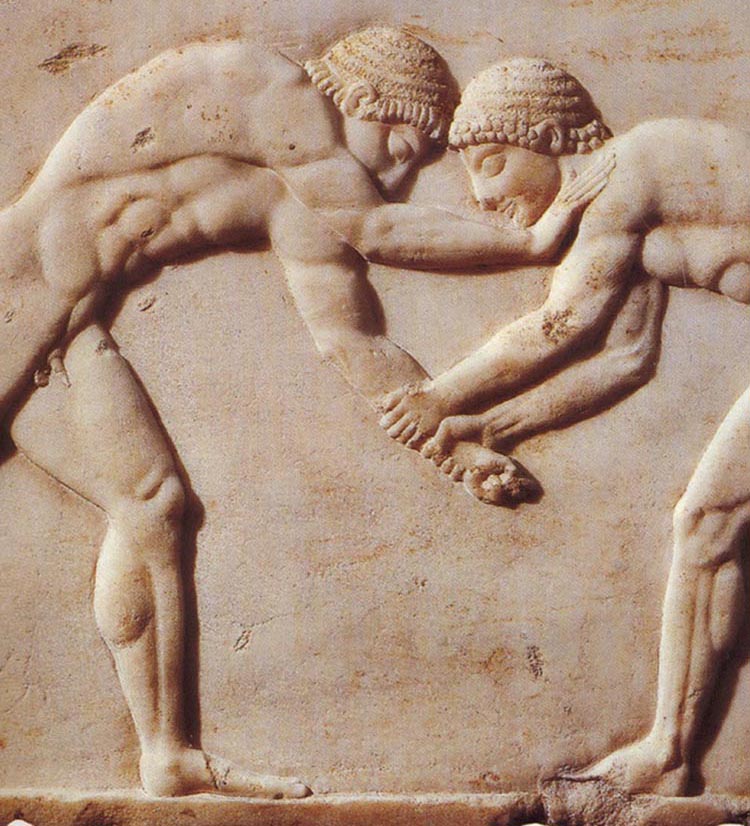

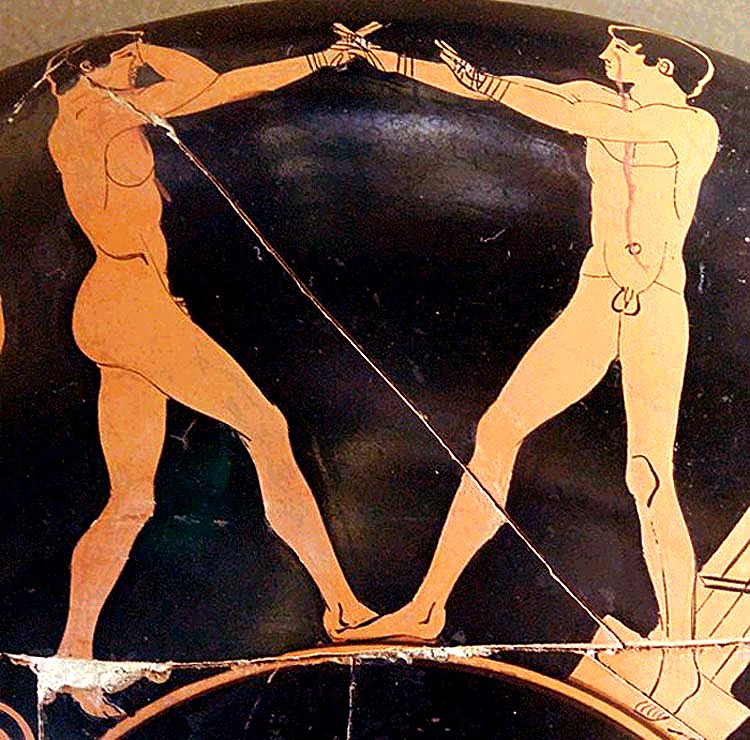

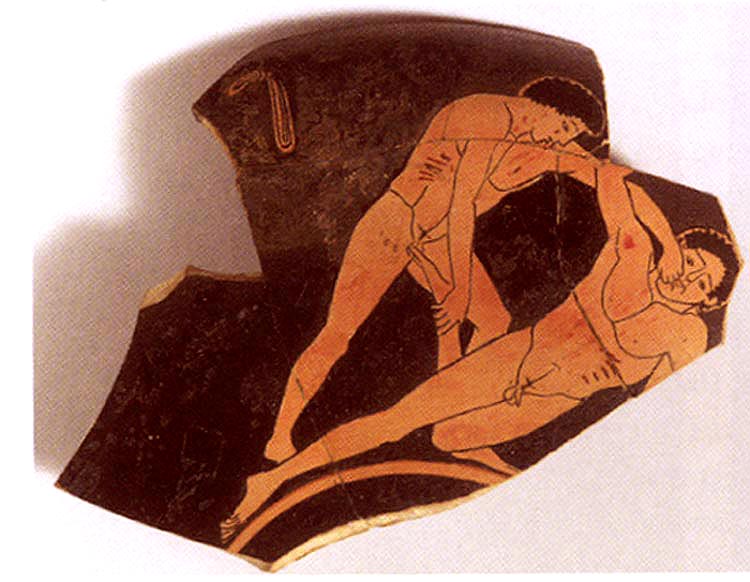

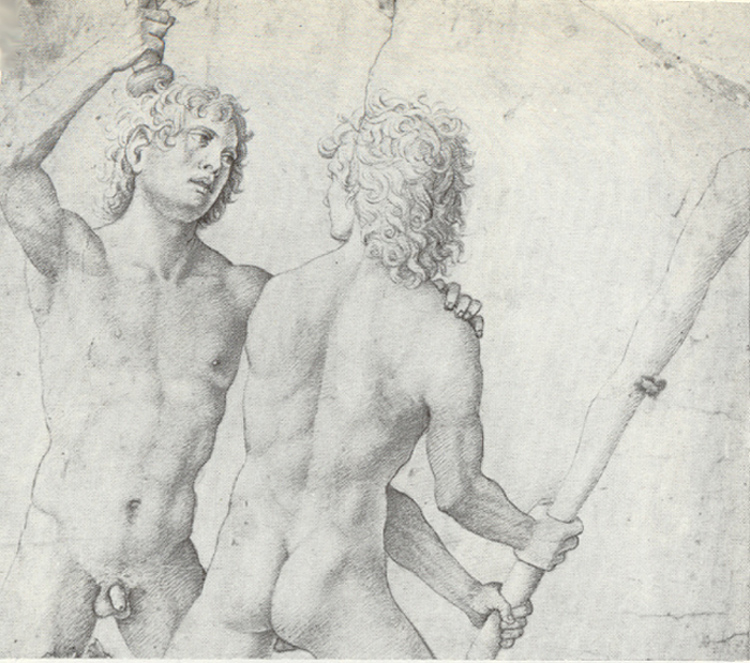

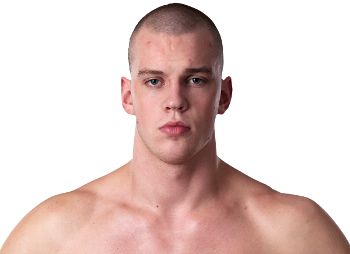

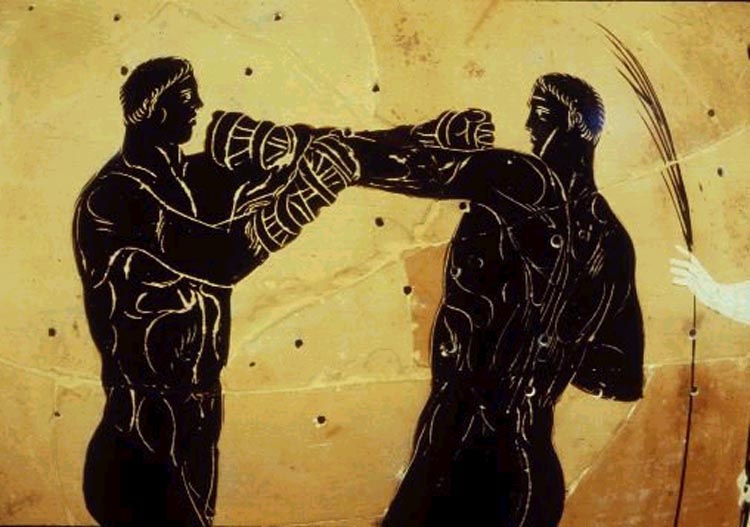

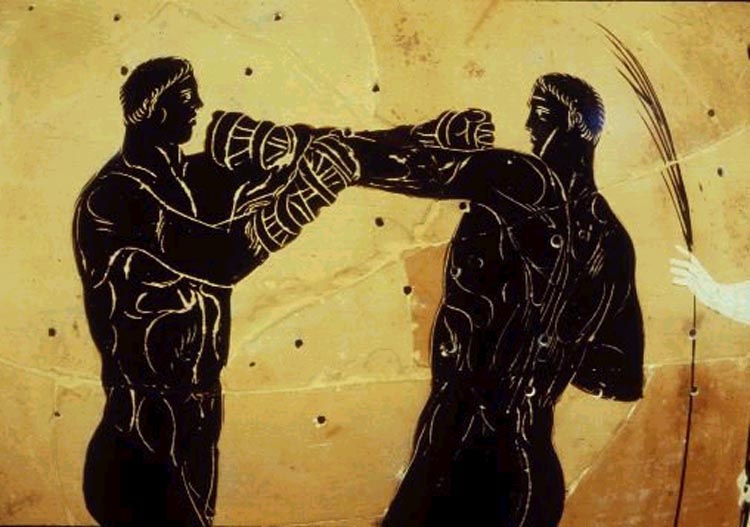

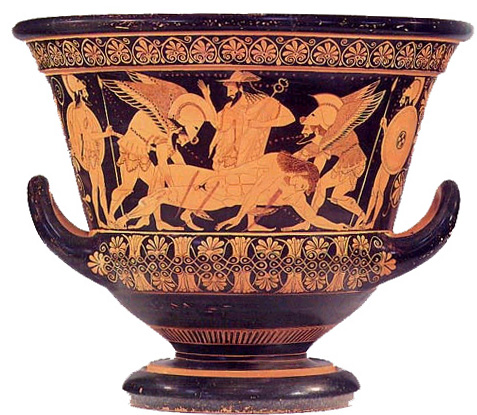

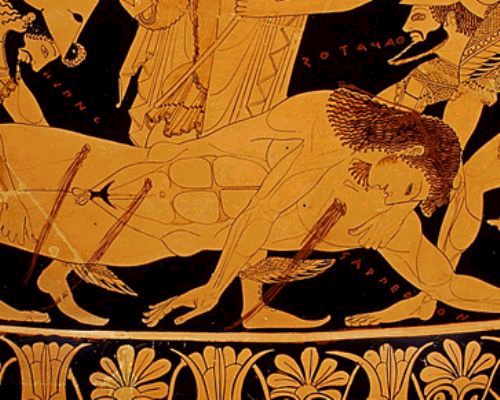

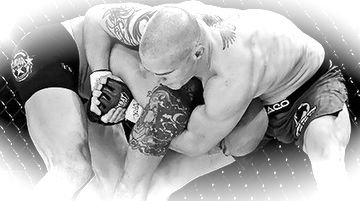

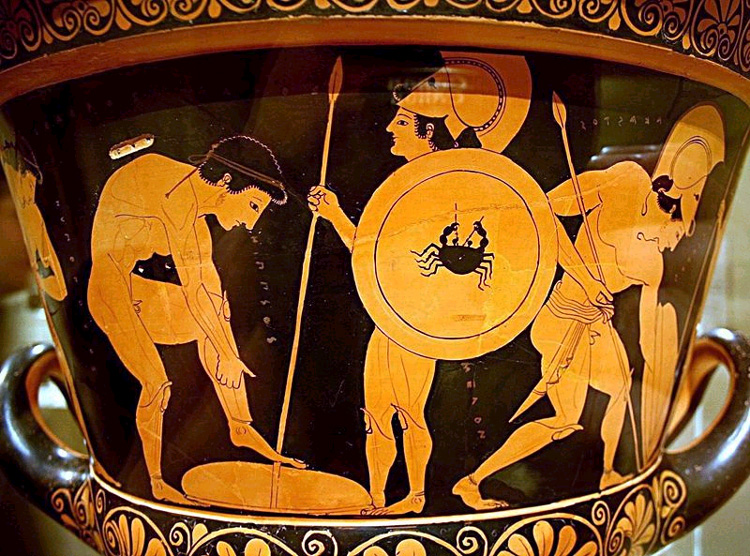

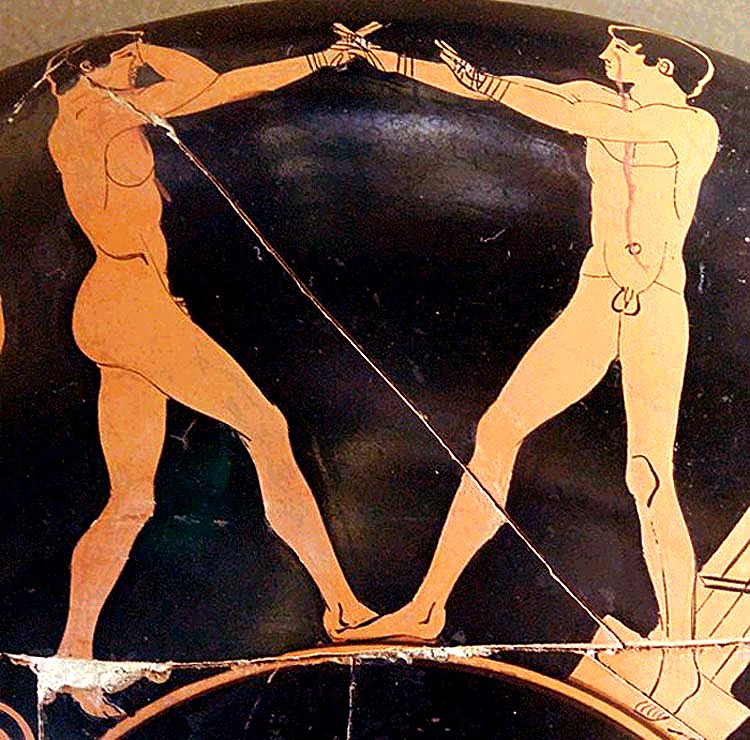

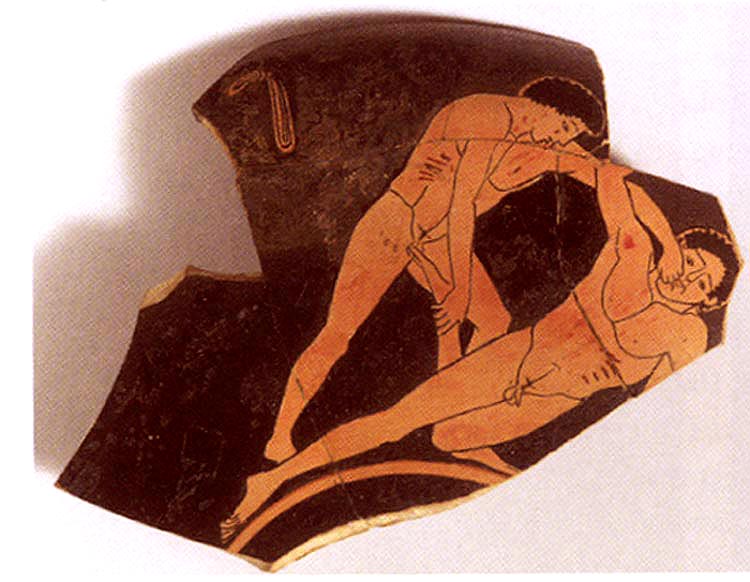

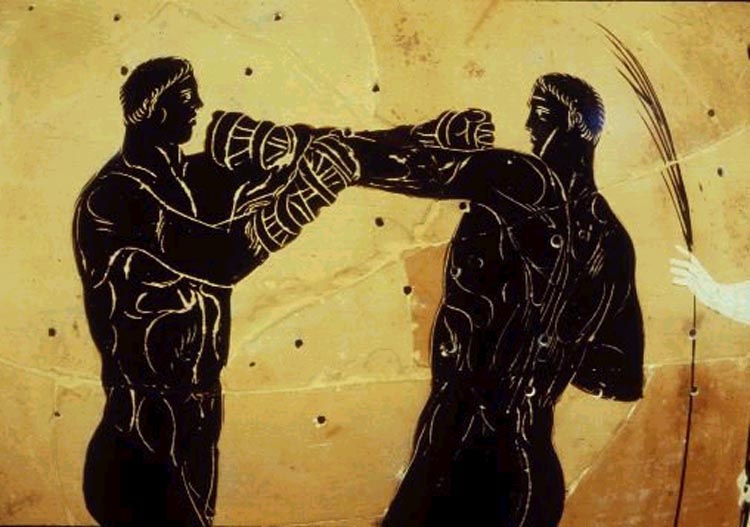

Which we can see using two masterpieces of Greek art, works which you often see in my articles because they epitomize classicist Werner Jaeger's statement that such images express an "ideal unity of physical and spiritual which . . . indicates how we must understand the athletic ideal of manly prowess" -- that is, Fighting Manhood.

In other words, these works of art express an Ideal -- as in Warrior World of Being / Warrior Kosmos -- of Manly Prowess -- which is Manly Moral Order -- which is Fighting Manhood.

Further, and as I talked about in Biblion Triton, notice how essentially serene these depictions of Fighting Manhood and Fight itself -- actually are:

Their serenity devolves from their source -- which is the Warrior Kosmos, the Warrior World of Being, where all is timeless and changeless, immutable and eternal.

The Fight -- and Fighting Manhood -- are Forever.

And guys, it's important you understand this:

In the Warrior World of Being, in the Warrior Kosmos, these two Nude Men, these two Nude Warriors -- are Locked in Combat -- for all Eternity.

Their Fight NEVER ends.

So:

When you look at this art, what you're seeing is Fight -- and Fighting Manhood -- under its ETERNAL aspect.

You're being given a glimpse of Fight -- ManFight -- in Eternity:

Moreover:

If, Fighting Manhood = Fight and Fight = Fighting Manhood -- which they do --

Then Proten Aitian, Primal Cause, is identical to

So -- and once again:

Because Fighting Manhood resides in the Warrior World of Being, the Warrior Kosmos, where it is, de facto, the Idea of Good, it's both the Primal Love and the Primal Cause of the Warrior All:

Of Brave Beauty -- kalokagathia ; and

Manly Moral Order ; and

All the other Excellences -- of Man:

So:

Fighting Manhood is the Sum and Father of All the Excellences of Man.

Corporeal, Mental, Moral, and Spiritual.

And those Corporeal, Mental, Moral, and Spiritual Excellences include --

Manly Moral Order -- which, as we'll eventually see, is essential to the well-being both of the Warrior himself -- and of his Warriordom.

Now:

I said that Fighting Manhood -- the Fight of Manhood Against Manhood -- ultimately resides in the Warrior World of Being -- the Warrior Kosmos.

Where the FIGHT -- is ETERNAL.

Where it's Man Against Man --

And Manhood Against Manhood --

Forever.

Fight Without End.

The Warrior Kosmos is the Warrior World of Being.

Eternal Fight -- Fight Without End -- exists -- it's REAL -- in the World of Being.

In the Word of Being, Two Men, Two Nude Men, Fight Each Other --

Man Against Man and Manhood Against Manhood -- FOREVER.

The Fighting we see in the World of Becoming -- is an approximation of that -- a

copy of it.

Even so, seeing that Fighting makes Men -- "wild" -- that is, it frees them from the societally-dictated ways of opinion -- and returns them to their natural selves -- because witnessing the Fight super-charges Men erotically and that erotic energy then powers the way to communion with and knowledge of the Absolute Fighting Manhood of the Warrior Kosmos.

Classicist RG Bury on Being and Becoming:

In making this distinction, Plato was not innovating : long before

him, [the philosopher] Parmenides had divided his exposition into two

sections, "the Way of Truth," and "the Way of Opinion," while

Democritus had drawn a sharp line of division between the "Dark

Knowledge" we have of sensibles and the "Genuine Knowledge" which

apprehends the only realities, the Atoms and the Void.

Both of those concepts really speak to me.

Fighting for me is the Way of Truth -- because it's the Way of Manliness.

That's why I use aphorisms in my work, aphorisms like The Way of the Warrior is the

Way of Salvation ; and Manliness Equals Life.

Because -- for Men, Manliness does equal Life.

And because The Way of the Warrior is the Way of Salvation.

For Men.

For Men, Manliness and Manhood and Manly Spirit -- are Life.

And when Democritus says Genuine Knowledge is Knowledge of the Atoms --

what I think is that in a real Fight, the Men are Fighting on an atomic level.

Every atom of their being is engaged in the Fight.

Sweat, Blood, Skin, Bone, Muscle -- and Cum too.

We know that if two guys cum in the same cunt -- or just on each

other's abs -- each Man's sperm will seek out the other's and try to

destroy it.

Sperm will literally Fight Sperm.

In a Fight, on a macro level, it's Man Against Man.

On a micro level, it's atom against atom.

Sweat Against Sweat and Blood Against Blood.

Every Atom Against Every Other Atom.

Total, Pure, Unrelenting Manhood.

Sokrates says that Ares is Arratos -- Hard and Unyielding, Hard and

Unbending, Hard and Unrelenting.

Unyielding, Unbending, Unrelenting Manhood.

Fighting Manhood.

Which is basic.

Foundational.

And goes to the heart of the Male Universe -- the Warrior Kosmos.

Fight -- Virtuous Struggle and Strife -- Fighting Manhood -- animates, is the Father of, All.

Including, reductionally, Manhood itself -- Manhood Man-ifested as Brave Beauty.

BIBLION TETARTON

By Bill Weintraub

Now -- an important question:

If Fight is the Father of All -- which de facto means that Manhood -- Fighting Manhood -- is the Father of All -- can we reconcile that idea with Plato's statement that Eros is the origin of all spiritual effort?

As you'll see, the answer is -- Yes -- and easily.

But to understand that answer, we have to first understand the intellectual world into which Plato was born.

Here's Paul Shorey, in the UN-abridged edition of his magesterial book What Plato Said:

He would find in nearly all of them the general conception of the reduction of this varied

world to unity or to a few interchangeable elements. He would find not of course his own explicit antithesis between materialism and spiritualism, but the provocation and stimulus of it in a steadily progressive tendency to conceive true science as the mechanistic explanation of all things and the negation of all divine intervention. He would find also a conception of cycles of change, growth, and decay not differing appreciably for any practical purpose from Herbert Spencer's cycles of evolution and dissolution, or the fancy of the most recent popularizer of the new physics that the disintegration and resolution of matter into heat may save the universe from the death by "entropy" with which nineteenth-century physics threatened it. And he would find in Anaximander, whom he does not mention, and others a more or less serious poetic and allegorical interpretation of such philosophies in the fancy that individual existence is an injustice for which the individual must pay the penalty by reabsorption into the infinite and indeterminate. An idea which

again for practical purposes does not differ appreciably from the

reflections in Tennyson's ancient sage:

For all that laugh, and all that weep

More specifically he would discover in Anaximander, Empedocles, and others, not of course the modern scientific doctrine of biological evolution, but its virtual equivalent for philosophical purposes, the hypothesis that life was somehow a spontaneous growth and that nature tried many experiments of which only the fitting survived, that the higher forms of life may have been outgrowths of the lower, that the prolonged infancy of man was a cause of the constitution of the family and so of the development of civilization; that the surface of the earth had been subject to vast changes in the long course of time.

Empedocles, Anaxagoras, and the atomists, Leucippus, and Plato's own contemporary, Democritus, would familiarize his mind with hypotheses about the ultimate constitution of matter which though not based on the mathematics that support and complicate similar speculations today produce substantially the same impression on the lay mind even of a philosopher.

From Heraclitus and the Eleatics he would derive the antithesis so vividly described by Pater, and that pervades his own philosophy, between the experience of incessant change and the intellectual and moral necessity of the assumption of stability. In Heraclitus he would

find the suggestion and the poetical or epigrammatic formulation of such extremely modern ideas as universal mutability, universal relativity, and yet a reign of law or reason somehow operating in and controlling the eternal process. In the Eleatics he would find the beginnings of that dialectic of being and not-being, the one and the many, the like and the unlike, which he himself in jest or in earnest was to push to the limit in anticipation of all verbal metaphysics from the neo-Platonists to the Scholastics and from the Schoolmen to Hegel and his successors.

[emphases mine]

What does Shorey tell us?

First of all, that the pre-Socratic Greek philosophers anticipated or just plain formulated first most of the scientific ideas we think of as "modern."

Translation:

Those ideas are not modern.

They originated in ancient Greece.

Then Shorey tells us that Plato "is said to have studied Heraclitus under Cratylus."

And indeed, Plato later wrote a dialogue titled the Cratylus.

Which discusses, among other things, the relationship between Ares and Manhood:

~Plat. Crat. 407d, translated by Fowler.

What you see there is that the name "Ares" -- because of its relationship to Arren -- Virility ; and Andreion -- Manhood ; and Arratos -- Hard and Unbending -- matters.

And that the name and idea of Ares -- that is, Ares as the personification of Manhood, Virility, Courage, Combat, and Fight -- like other hypostatized concepts -- provides *stability* -- in a world of constant change and flux.

Which Shorey in essence confirms -- and it's the crucial bit:

In Heraclitus he would find the suggestion and the poetical or epigrammatic formulation of such extremely modern ideas as universal mutability, universal relativity, and yet a reign of law or reason somehow operating in and controlling the eternal process.

So -- from Heraclitus, and from his own deeply-held beliefs about the nature of the universe, beliefs which were supported by Sokrates, Plato determined that there is an "intellectual and moral necessity of the assumption of stability"; and "a reign of law or reason somehow operating in and controlling the eternal process."

That reign of law and reason exists, of course, in the World of Being -- which we explored in Biblion Deuteron -- Primal Love ;

and, for which World of Being, there is both an intellectual and moral necessity.

And we began to explore the intellectual necessity for the World of Being in Biblion Triton -- UN-forgetting.

Now:

It's clear, and both Jaeger and Shorey agree, that Plato got the notion of the World of Becoming from Heraclitus via Cratylus, and that of the World of Being from Sokrates.

According to Aristotle, says Jaeger,

As a young student, Plato attended the lectures of the Heraclitean Cratylus, who taught that everything flows and nothing has a permanent existence.

Then, when he met Socrates, a new world opened up to him. Socrates confined himself entirely to questions of morality, and tried to discover the eternal essence of the Just, the Beautiful, the Good, etc.

At first glance, the idea that everything changes, and the assumption that there is a permanent truth, seem to be mutually exclusive.

But Cratylus had so convinced Plato that everything changes, that his conviction could not be shaken even by the powerful impresssion he received from Socrates' determined search for a fixed point in the ethical world.

Plato therefore concluded that Cratylus and Socrates were both right, because they were speaking of two different worlds.

Cratylus' statement that everything flows referred to the only world he knew -- the world of sensible phenomena; and Plato continued even later to maintain that the doctrine of eternal change was true for the world of sense.

But Socrates, in the search for the conceptual essence of those predicates like 'good', 'just', 'beautiful', on which our existence as moral beings is based, was looking towards a different reality, which does not flow but truly 'is' -- because it remains immutably and eternally the same.

[emphasis mine]

So: The "conceptual essence of concepts like Good, Just, Beautiful" -- which reduce, as you've seen, to Manhood -- remains "immutably and eternally the same."

Key point: Our existence as Moral beings -- that is, as human beings -- must be based upon a reality which remains immutably and eternally the same.

Shorey agrees, but his analysis, as befits Shorey, is more complex:

~Merriam-Webster's Ninth Collegiate Dictionary, 1983

In Kant, a phenomenon is an object of sense ; thus Plato's sensible realm becomes Kant's phenomenal, while the intelligible is the noumenal ; and --

all power originates in the noumenal realm and flows to the phenomenal.

That must be so, since the original forms, essences, ideas, etc must be more powerful than their copies.

Shorey:

From Heraclitus to John Stuart Mill human thought has always faced the alternative of positing an inexplicable and paradoxical noumenon, or accepting the "flowing philosophy [ie, all is in flux]." No system can escape the dilemma. Plato from his youth up was alternately fascinated and repelled by the philosophy of Heraclitus. No other writer has described so vividly as [Plato] the reign of relativity and change in the world of phenomena. Only by affirming a noumenon could he escape Heracliteanism as the ultimate account of (1) being, and (2) cognition. He chose or found this noumenon in the hypostatized concepts of the human mind, the objects of Socratic inquiry, the postulates of the logic he was trying to evolve from the muddle of contemporary dialectic, the realities of the world of thought so much more vivid to him than the world of sense. This is the account of the matter given by Aristotle and confirmed by the dialogues. Except in purely mythical passages, Plato does not attempt to describe the ideas any more than Kant describes the Ding-an-sich [thing in itself, the thing as such] or Spencer the "Unknowable." He does not tell us what they are, but that they are. And the difficulties, clearly recognized by Plato, which attach to the doctrine thus rightly limited, are precisely those that confront any philosophy that assumes an absolute.

[Shorey goes on to say that since Plato's time, philosophers, including Locke, Berkeley, JS Mill, and Taine, have worked out a partial solution to the problem.]

. . .

But the main issue is unaffected by this fact. Even if he had been acquainted with the analysis of Mill and Taine, Plato would have continued to ask : Are the good and the beautiful and similar essences something or nothing? Can everything in the idea be explained as the natural product of remembered and associated sensations? Is not man's power of abstraction something different in kind from any faculty possessed by the brute?

Not all the refinements of the new psychology can disguise the fact that the one alternative commits us to the "flowing philosophers," the other to some form of Platonism. For the answer that the "good" and the "beautiful" are only concepts of the mind is an evasion which commends itself to common-sense, but which will satisfy no serious thinker. If these concepts are the subjective correlates of objective realities, we return to the Platonic idea -- for Plato, it must be remembered, does not say what the ideas are, but only that they are in some sense objective and real.

[emphases mine]

~archive.org, The Unity of Plato's Thought

Plato "does not say what the ideas are, but only that they are in some sense objective and real."

In other words, they constitute a "noumenon" -- something you're sure exists, something you're certain is objective and real, but which you know can't be experienced, and to which attributes cannot be intelligibly ascribed.

You can, says Shorey, use myth in an attempt to describe the noumena, for, as Jaeger says,

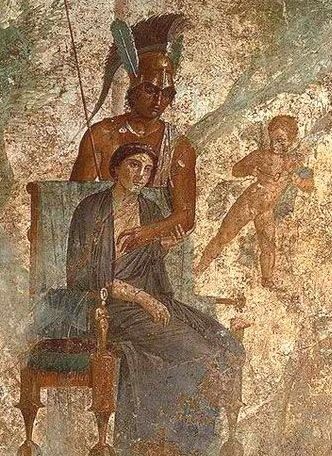

For example, in the myth, Ares, God of War, fucks Aphrodite, Goddess of Sex.

And as you can see, His amorous efforts leave him, at least according to Botticelli, worn out.

And surrounded by young and playful satyrs, who, it would appear, seek to re-awaken Him -- to Love.

But His libidinous labors, and those of Aphrodite, will have been well worth the cost, for the child -- actually a youth -- which results from their coupling is Eros -- the God of Romantic Passion.

The myth gives the supposition -- that the union of War and Sex produces Manly Romantic Passion -- form and color.

Here's a Roman version:

The depiction of Ares and Aphrodite is touching.

But Greek Eros has become infantilized -- he's now a Roman Cupid.

Nonetheless, you can, in this wall painting, plainly see how the myth gives supposition -- form and color.

So: you can use myth in attempting to describe the Ideas, Essences, and Forms.

And, I would say, you can use metaphor.

And you can certainly speak of your own, subjective, experience, as I have and NW has.

But:

It's *not* just subjective.

Because:

Here's what's at issue:

What do you you think?

Is Manhood -- something or nothing?

As we saw in Biblion Triton -- Book III -- if Manhood (or any other essence) is nothing but a passing thought -- changes in the world of becoming -- would and will wipe it out.

But if, we assume, it is "self-subsistent" -- self-existing -- independent of the world of becoming -- in a noumenon which Plato calls the World of Being -- it will exist forever, immutable and eternal.

And without that assumption, there's no satisfactory way to explain -- the human experience.

Shorey:

If the concepts in the human mind, concepts like Manhood, are "the subjective correlates of objective realities" --

That is, if a concept like Manhood in someone like NW's mind -- corresponds to an objective reality -- the Absolute Manhood in the World of Being -- Manhood exists, and NW's (and my own) accessing it as a child -- becomes explicable.

Shorey:

Why doesn't Plato say what the ideas are -- physically, that is?

Because, again, they're "noumena" -- objects and concepts which he and we know to exist, but which cannot be experienced, and to which no attributes -- such as height and weight -- can be "intelligibly" -- that is, reasonably -- ascribed.

So -- Plato and Bill Weintraub -- know that Absolute Fighting Manhood exists, as an Essence, a Form, an Idea, and an Ideal -- in the World of Being -- the noumenal realm.

But -- Plato and Bill Weintraub know that we can't experience that Idea -- in the sense of sensory experience -- for example, touch; nor can we reasonably give it attributes such as height and weight.

We can only say, based on our intellect, our reason, that it is in some sense objective and real.

And, that in my case, and that of NW, too, it informs everything we do.

Which makes it, functionally, and for both of us, the Idea of Good -- the Good Purpose in some Controlling Mind able to achieve that Purpose -- and the Sanction -- the Consideration, Principle, or Influence, which impels to Moral Action and determines Moral Judgment.

For, as Werner Jaeger says, paraphrasing Plato, "It is knowledge of the true standard which inevitably dictates our choice and determines our will."

It is knowledge -- gained in the World of Being -- of the true standard -- the Idea of Good, Fighting Manhood -- which inevitably dictates our choice and determines our will.

Now: Shorey emphasizes, in the passage we've just read, the conflict between Heraclitean flux and Platonic stability.

Nevertheless, it's important to remember, and Shorey also says, that Heraclitus, while stressing flux, also talks about the "truth" -- that is, Immutable and Eternal Truth -- that can be found in names -- that is, Ideas -- and thus suggests "a reign of law or reason somehow operating in and controlling the eternal process."

As in --

So: the important thing to understand is that Plato believed very strongly that there had to be stability, "a reign of law or reason operating in and controlling the eternal process."

That the Universe -- the Kosmos -- is not just about atoms colliding meaninglessly in the void -- but that the Kosmos has and must have -- a Moral Center.

Must.

And it's Plato who, among the Greeks, first uses the word Kosmos in the sense of "the world or universe, from its perfect order."

And for Plato, that Moral Center, that Moral Core, that Kosmic Moral Order -- resides in or is otherwise associated with -- the World of Ideas.

Now -- having, I hope, a better understanding of the intellectual milieu into which Plato was born and grew up -- and, more importantly, why he reasoned as he did -- let's get back to this question:

If Fight is the Father of All -- which de facto means that Manhood -- Fighting Manhood -- is the Father of All -- and remembering that both Manhood and Eros are Ideas, Forms, Essences, and Ideals in the World of Ideas -- that is, the World of Being -- how can we reconcile "Fight is the Father of All" -- with Plato's statement that "Eros is the origin of all spiritual effort?"

As you'll see, the answer is -- easily.

Fighting Manhood -- which is personified by the hypostatized Ares -- is the Father of All.

And Ares, as it happens, in Greek myth, is the Father of Eros -- Romantic Passion, particularly between Men.

That same Eros, you'll remember from the closing section of Biblion Proton, is an Agonist -- a Fighter.

He and his twin AntEros are Agonist and AntAgonist -- They Fight.

Not surprising, given that they're Sons of Ares -- the God of Fight and Fighting Manhood.

Now, and please understand: Eros and AntEros are, for purposes of myth, and even, as we'll see, materialization, two beings ;

But -- together they constitute a Unit and a Unity, which we call, and which is -- EROS.

The God of Manly Romantic Passion.

How can that be?

Well, as Sallustius, a fourth-century AD Neo-Platonist and Hellenist says,

~Sallustius, Concerning the Gods and the Universe, translated by Nock.