A G O G E

the spear-points of young men blossom there

Part IV

Excellence, Honor, and the Molding of Men

6-10-08

Hi Guys.

We here continue our discussion and exploration of the Spartan Agogé.

There have been three previous posts:

If you haven't read them, please take a look -- they have a lots of good and important info -- and are richly illustrated too.

This page continues our discussion with an exploration of Excellence, Honor, and the Molding of Men.

And it's divided, appropriately, into three parts:

Honor; and

This is a long post.

But it's one I want you to read, both because it's important in its own right; and because I'll be referring back to it in upcoming posts.

What I recommend people do is read one section at a time:

First

Excellence; then

Honor; and then

Thanks guys.

Bill

In my last reply to an attack on men being together, I introduced the Greek word and concept of "areté," which for the time being we can define as Warrior Excellence:

that is, the Warrior's unceasing quest to excel as both a Warrior and a Man.

And to better understand the concept of Excellence, and its relationship to Honor, starting with the Homeric Greeks, and going forward to the Athenian Golden Age of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, we're going to look at the work of one of the greatest scholars of ancient Greece, Werner Jaeger.

I've mentioned Jaeger before in a number of posts, but this will be your first full introduction to Jaeger, who's without question one of the great thinkers about the Greeks.

Jaeger was a 20th-century German classicist who eventually had to flee Germany and Hitler, and who in later years taught at Harvard.

His most famous book is Paideia: The Ideals of Greek Culture.

It's a work of tremendous scholarship, and I highly recommend it.

Indeed, there are no superlatives I can use, which would be adequate to this book.

There are many books about aspects of Greek culture.

And there are many books which attempt to sum up Greek culture.

And then there's Werner Jaeger's Paideia -- which has no equal.

Paideia, by the way, is pronounced Pie-day-a -- short "a" -- and the word originally meant child-rearing;

but it eventually came to have the highest meaning of "Culture" the Greeks and the Greek language possessed.

For, as we'll see, the Greeks came to believe that Paideia -- the molding, or, we might say, making, of the Man through education in its broadest sense -- was the highest act of their civilization.

And Jaeger's exposition of Paideia -- is brilliant.

Volume I, which is easy to find used and relatively cheap, will take you from Homer through Plato.

And it's a wonderful journey.

Like I said, Jaeger was German -- he had to flee Germany because he refused to divorce his Jewish wife -- and his book, in a sense, is the culmination of more than two centuries of very fine German scholarship dedicated to ancient Greece.

But it's also a lot more than that.

Here's Jaeger in his own words from the Introduction:

The unique position of Hellenism in the history of education depends on the ... supreme instinct to regard every part as subordinate and relative to an ideal whole -- for the Greeks carried that point of view into life as well as art -- and also on their philosophical sense of the universal, their perception of the profoundest laws of human nature, and of the standards based on them which govern the spiritual life of the individual and the structure of society. For (as was realized by Heraclitus, with his keen insight into the nature of the mind) the universal, the logos, is that which is common to all minds, as law is to all citizens in the state. In approaching the problem of education, the Greeks relied wholly on this clear realization of the natural principles governing human life, and the immanent law by which man exercises his physical and intellectual powers.

To use that knowledge as a formative force in educatlon, and by it to shape the living man as the potter moulds clay and the sculptor carves stone into preconceived form -- that was a bold creative idea which could have been developed only by that nation of artists and philosophers. The greatest work of art they had to create was Man. They were the first to recognize that education means deliberately moulding human character in accordance with an ideal. 'In hand and foot and mind built foursquare without a flaw' -- these are the words in which a Greek poet of the age of Marathon and Salamis describes the essence of that true virtue which is so hard to acquire.

Only this type of education deserves the name of culture, the type for which Plato uses the physical metaphor of moulding character. The German word Bildung clearly indicates the essence of education in the Greek, the Platonic sense; for it covers the artist's act of plastic formation as well as the guiding pattern present to his imagination, the idea or typos.

Throughout history, whenever this conception reappears, it is always inherited from the Greeks; and it always reappears when man abandons the idea of training the young like animals to perform certain definite external duties, and recollects the true essence of education. But there was a special reason for the fact that the Greeks felt the task of education to be so great and so difficult, and were drawn to it by an impulse of unparalleled strength.

That was due neither to their aesthetic vision nor to their "theoretic" mentality. From our first glimpse of them, we find that Man is the centre of their thought. Their anthropomorphic gods; their concentration on the problem of depicting the human form in sculpture and even in painting; the logical sequence by which their philosophy moved from the problem of the cosmos to the problem of man, in which it culminated with Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle; their poetry, whose inexhaustible theme from Homer throughout all the succeeding centuries is man, his destiny, and his gods; and finally their state, which cannot be understood unless viewed as the force which shaped man and man's life -- all these are separate rays from one great light. They are the expressions of an anthropocentric attitude to life, which cannot be explained by or derived from anything else, and which pervades everything felt, made, or thought by the Greeks.

Other nations made gods, kings, spirits: the Greeks alone made Men.

~ Jaeger, xxii

The Ideals of Greek Culture -- indeed.

Jaeger: "The greatest work of art [the Greeks] had to create was Man."

"Other nations made gods, kings, spirits: the Greeks alone made Men."

And when we think about the AGOGE -- it's very important to understand that.

That the AGOGE is part of the Greek effort to create Man.

It's education in its best sense.

The Greeks, says Jaeger, were a "nation of artists and philosophers":

They were the first to recognize that education means deliberately moulding human character in accordance with an ideal.

"deliberately moulding human character in accordance with an ideal."

That's what the AGOGE was about.

The other Greeks admired Sparta.

They admired the Spartan Constitution and the Spartan state.

Why?

Jaeger: the Greek state "cannot be understood unless viewed as the force which shaped man and man's life."

The Greeks admired the way the AGOGE shaped man and man's life.

AGOGE.

The "g's" are hard in the word -- like the "g" in "get."

And all three syllables are pronounced.

AGOGE.

And while I know that the word probably sounds foreign and exotic to you, it's from the same root as "agogia."

As in our English word "pedagogy."

So we need for a few moments to talk about Greek words.

Let's start with the word "areté."

You'll notice that it has an accent on the last "e."

In point of fact, all Greek words have accents, and those accents are integral to the word -- that is, when written in the Greek alphabet, the accent must be there.

But as a practical matter, when we transliterate a Greek word using the Roman alphabet, we don't normally include the accent -- since English is not accented.

In this case, I wanted to show you the word "areté" with its accent, so that you'd know that all three syllables are pronounced, with the accent falling on the last syllable.

And that's all you need to know -- which is why I won't repeat the accent every time we use the word.

So: the problem with Greek words isn't so much that they're Greek, of course, as it is that they're written in the Greek alphabet.

Which most people don't know.

And which makes them seem inaccessible.

But actually they're not; and we use a lot of Greek-derived words in English.

For example, "human being" in Greek is anthropos -- as in anthropology.

"Hear" is acouo -- as in acoustic.

"Voice" is phoné -- as in phone -- telephone, phonograph.

Woman is gyne -- as in gynecology.

And Man is andros -- as in androgen.

Now -- we've talked about the Latin word for man, vir, and its related words virilis -- manly or masculine -- and virtus -- virtue.

So in Latin you can clearly see the relationship of vir -- virilis --virtus --

Man -- Manliness -- Virtue.

In Greek, we have andros -- man -- and andreia -- manliness.

But then, the word for virtue, or excellence, is areté.

That appears to have no relationship to andros -- for man.

Until we look a bit more closely.

And in order to look more closely, we're going to use the standard Ancient Greek-English lexicon, which is titled, appropriately, "Liddell and Scott's Greek-English Lexicon"; and I, like many people, use the abridged version, which is known as "The Little Liddell."

Though it's by no means little.

Again, "The Little Liddell" is what most people use, and I'm using the 1909 edition, which was reprinted in 2007.

So, relying upon The Little Liddell, the first thing we come to understand is that in Greek there are root words.

For example, AGO -- to teach.

From AGO comes agogia -- teaching -- as in paidagogia --

pais = child; agogia = teaching; so paidagogia = the education of children;

which is also, as I noted above, a word in English -- pedagogy.

And from AGO also comes -- AGOGE

So what we have is:

AGO

AGOGIA

AGOGE

All three words relate to education and teaching in a very broad sense.

Another root word is AGON -- meaning contest.

From AGON comes the word agonia --

Which Liddell defines as "1. a struggle for victory; 2. gymnastic exercise, wrestling; 3. of the mind, agony, anguish."

Then there's MACHE -- a battle, fight, combat.

All sorts of words are derived from MACHE.

Including machetes -- warrior.

What about the Greek word for virtue?

Is there anything in Greek which produces that Vir -- Virilis -- Virtus progression we know from Latin?

The answer is Yes.

But that being Greek, the progression is a bit more complicated -- and actually, more interesting.

Now, to start, we should be clear that there are words which derive from andros or Man which have the sense of both manliness and virtue -- for example, andreia, as I pointed out, means manliness, manly spirit, courage -- virtue; and there's a word eu-andria -- eu = good; andros = man; eu-andros, says Liddell, means "abounding in good men and true"; while eu-andria means abundance of men, thus manhood, manliness, courage, spirit.

And notice how the Greeks relate manliness to the male group -- an "abundance of men."

That's exactly what my foreign friend says: that the masculinity of men flows from their male group.

The masculinity of men flows from their group. It's like their natural masculinity combines and gets manifold when masculine identified men unite. The camaraderie, mutual understanding, support, playing together, learning the ways of the world as a male, dealing with roughs and toughs of life together --- they all help to develop the natural masculinity that exists within him.

So "euandria" -- an abundance of Men -- is, the Greeks understood, a good thing, gifting Men with Manhood, Manliness, Courage, and Fighting Spirit.

But what about "areté" -- excellence -- where does that come from?

Well, we already know from our earlier discussions of Jaeger that in Homer, which again is the Bible of the Greeks, areté or excellence means a combination of valour in battle and courtly morality.

So the Homeric "areté" has its roots in battle.

But it's not just that.

Because according to Liddell, the word areté derives from the root word --

ARES -- the god of war.

And that's really interesting.

This is what Liddell says:

From the same root [ARES] comes areté [excellence]; areion [better, stronger, braver -- the comparative of agathos or "good"]; ari- [a prefix, about which we'll talk more]; and aristos [best or elite] -- the first notion of goodness being that of manhood, bravery in war; cf. Lat. virtus.

So -- Liddell is telling us that the Greeks, like the Romans, made an explicit association between valour in battle and virtue:

From the same root [ARES] comes areté [excellence] ...the first notion of goodness being that of manhood, bravery in war; cf. Lat. virtus.

The first notion of goodness is bravery in war, manhood.

Manhood.

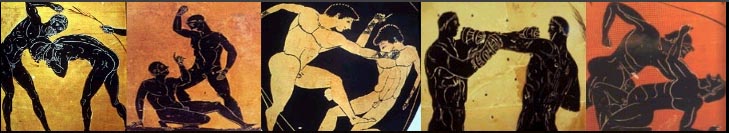

So -- for the Greeks, Fighting and Fighting Spirit -- Manhood -- are core to Excellence.

Fighting.

Fighting in War -- Fighting in Athletics.

They're connected.

And that connection is pervasive in Greek life.

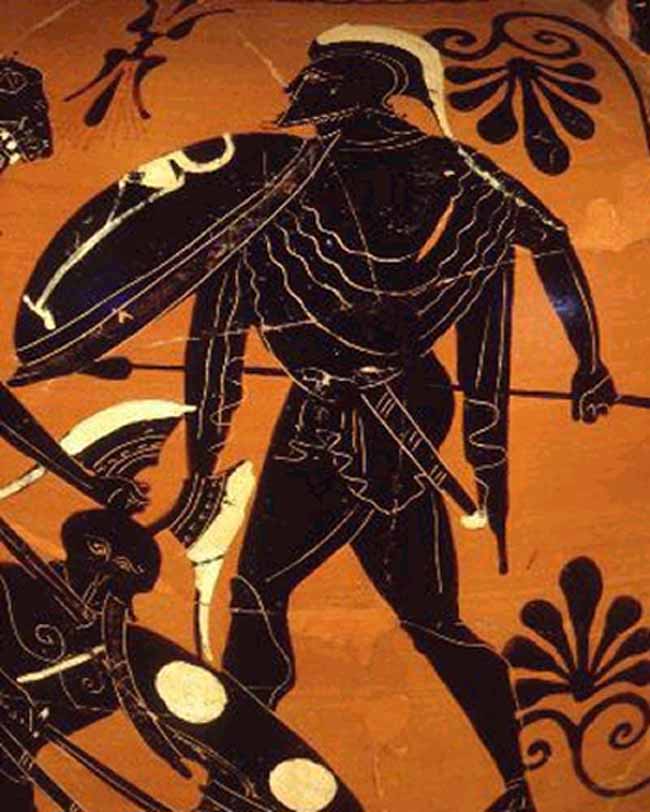

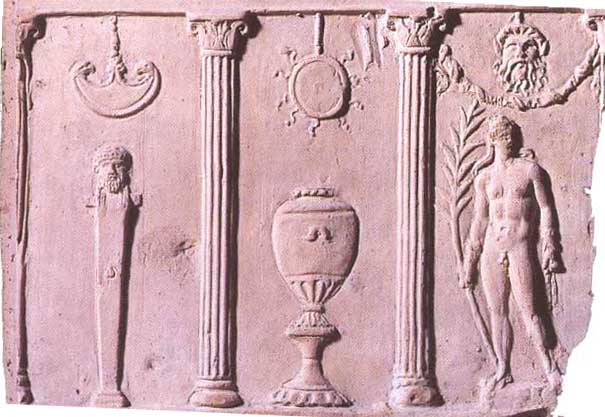

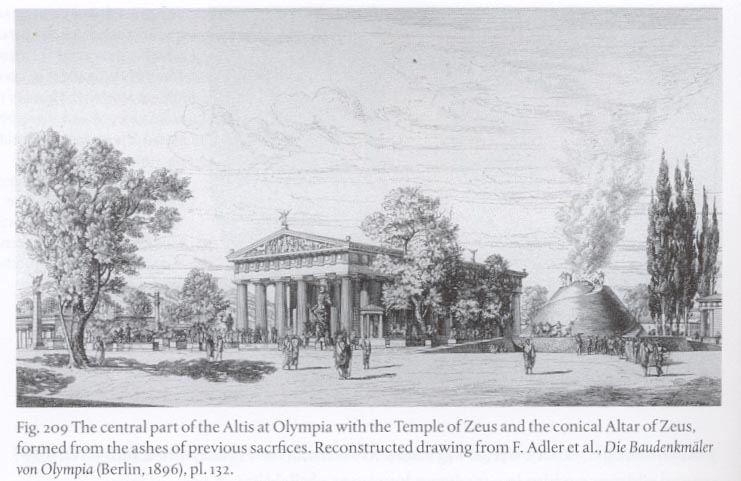

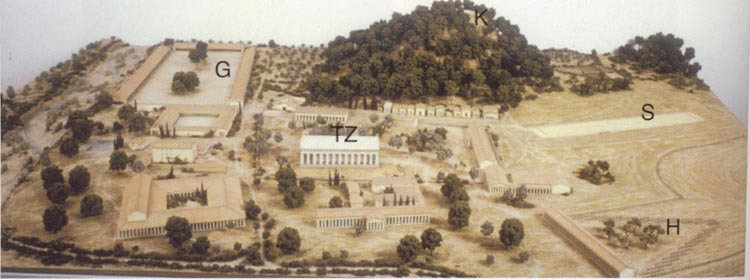

Pausanias, for example, a second-century AD Greek author who wrote a "Description of Greece," a description which concentrates on religious sites such as hero shrines and temples and sanctuaries, tells us that at the Olympic complex in Elis there stood "a statue of Ares with Agon by his side."

The War God -- Ares -- and the personificiation of Agon or Athletic Contest -- stand side by side in the sacred enclosure at Olympia.

And areté -- excellence -- derives from Ares himself.

Now, the Little Liddell said that also derived from ARES are words with an ari- prefix.

Let's look at a few:

- aristeia -- "the feats of the hero that won the meed of valour; any great, heroic action". And indeed, Liddell points out that at one time, books of the Iliad were labeled according to their Hero's deeds, as in "Book V, Diomedes' Aristeia" -- Diomedes' great and heroic deeds.

- aristia -- "the prize of the bravest, the meed of valour."

- aristeus -- "the best man"

- aristeuo -- "to be the best [or] bravest"

- aristo-kratia -- "the rule of the best-born [or] nobles"

- aristo-machos -- "fighting best"

So: all these words which mean "best," are connected to and derived from Ares, the god of war, and Areté -- Warrior excellence -- or -- Virtue.

And we can see that the root word ARES can even be combined with the root word MACHE to give us "aristo-machos" -- "fighting best"

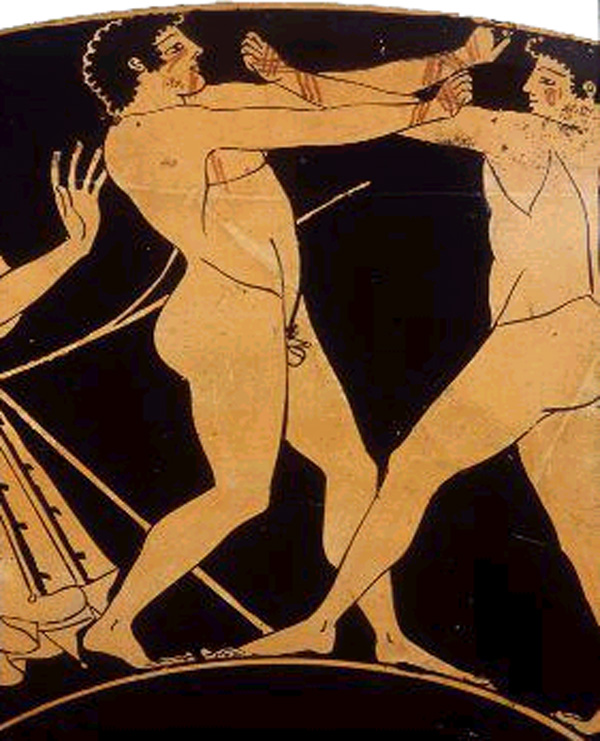

And it's worth noting in that regard that the Greeks often used the word we associate with athletic contests -- AGON -- interchangebly with the word for combat -- MACHE.

So that a battle might be referred to as an Agon.

And an athletic contest -- a Mache.

Once again, at Olympia, Ares and Agon stand side by side.

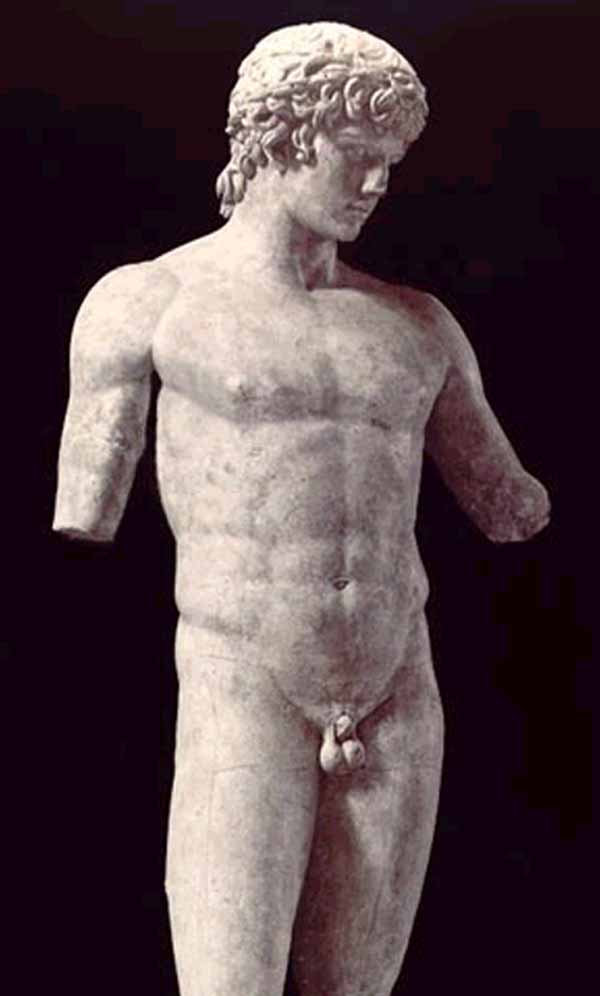

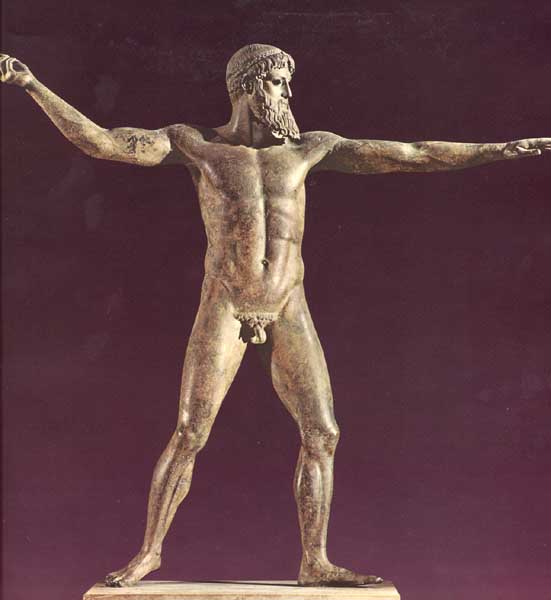

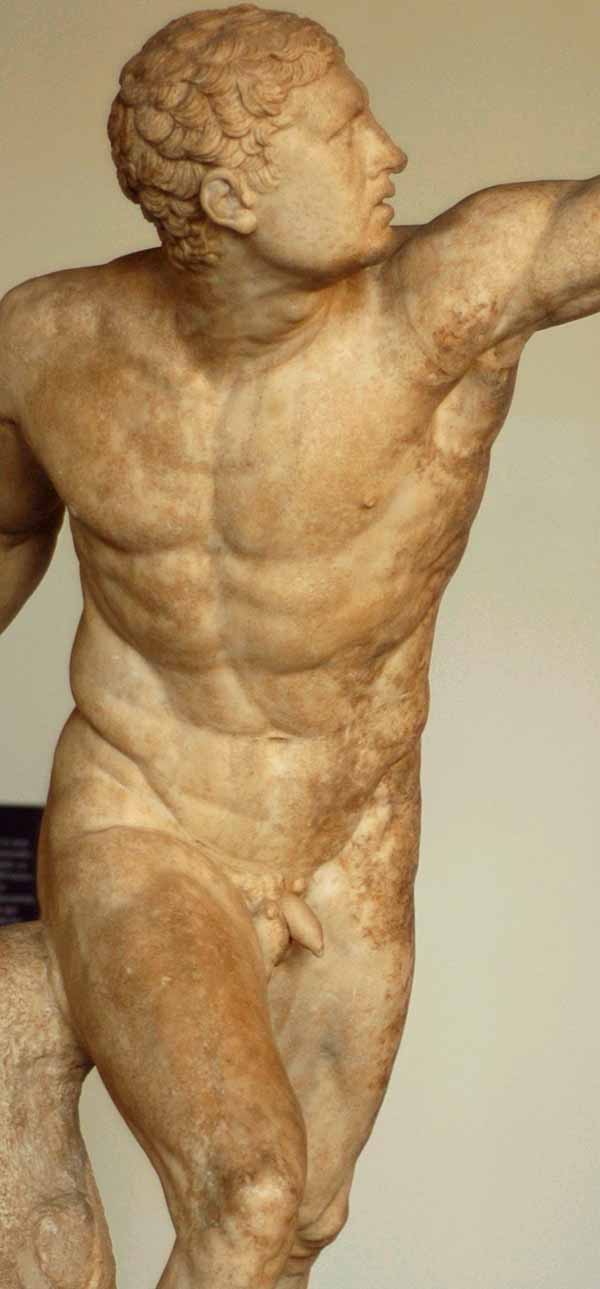

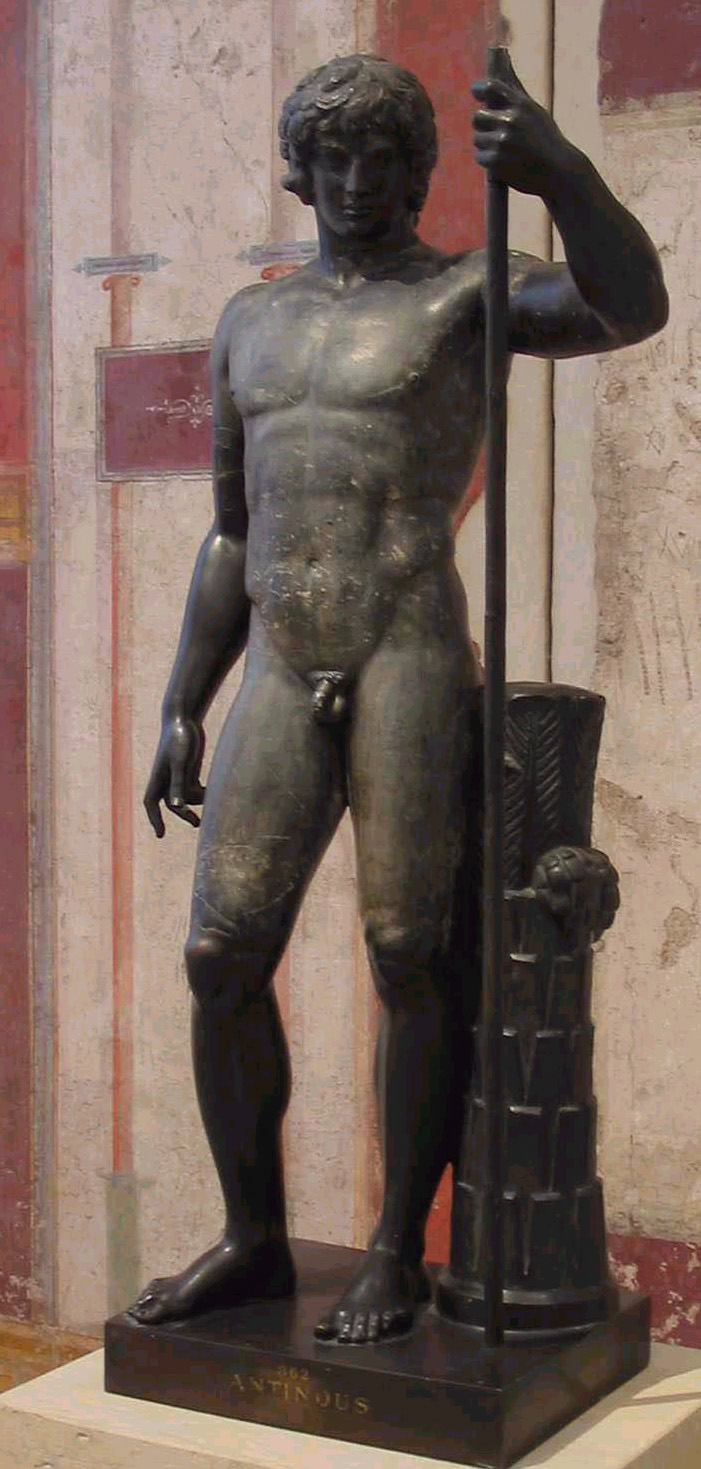

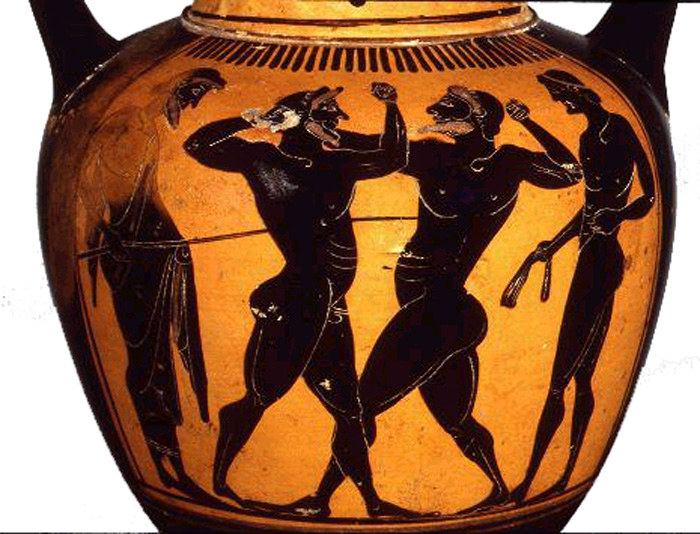

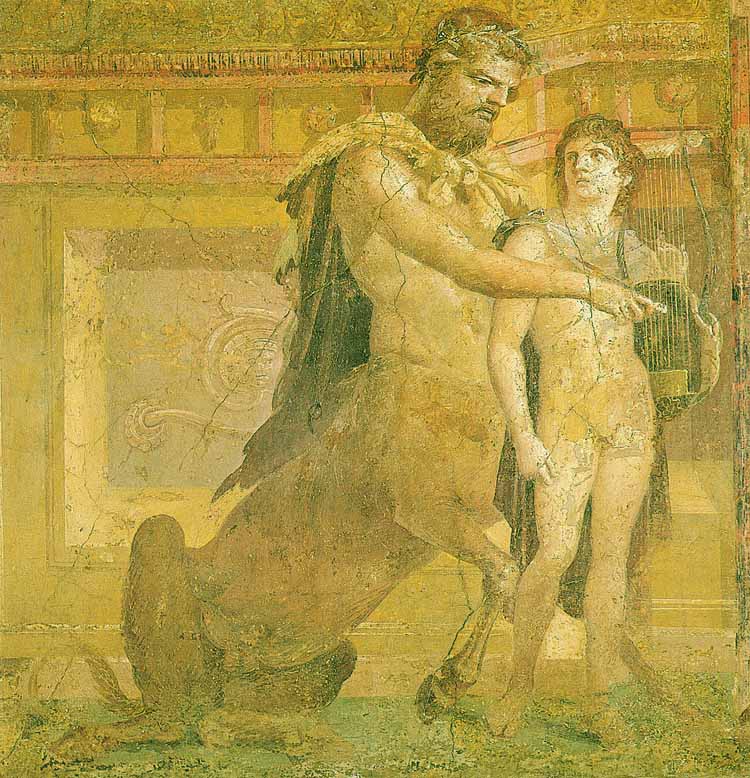

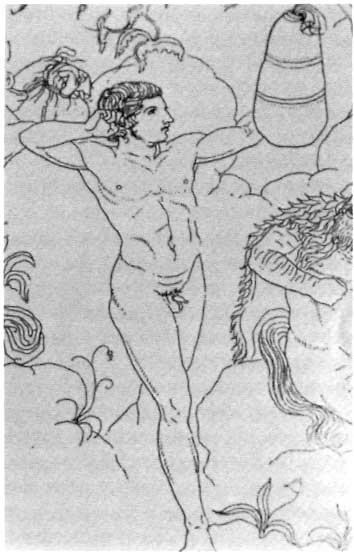

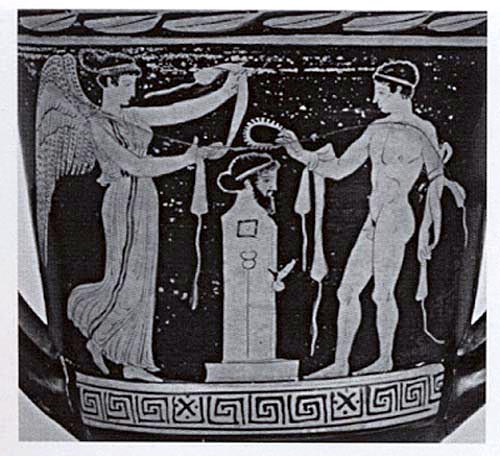

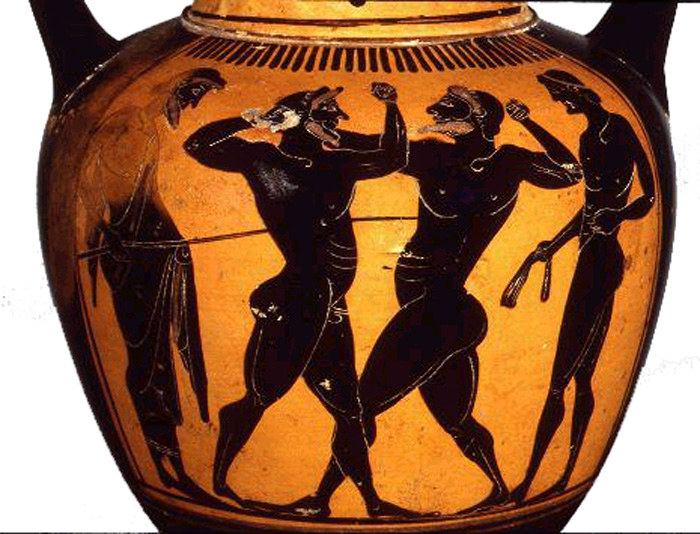

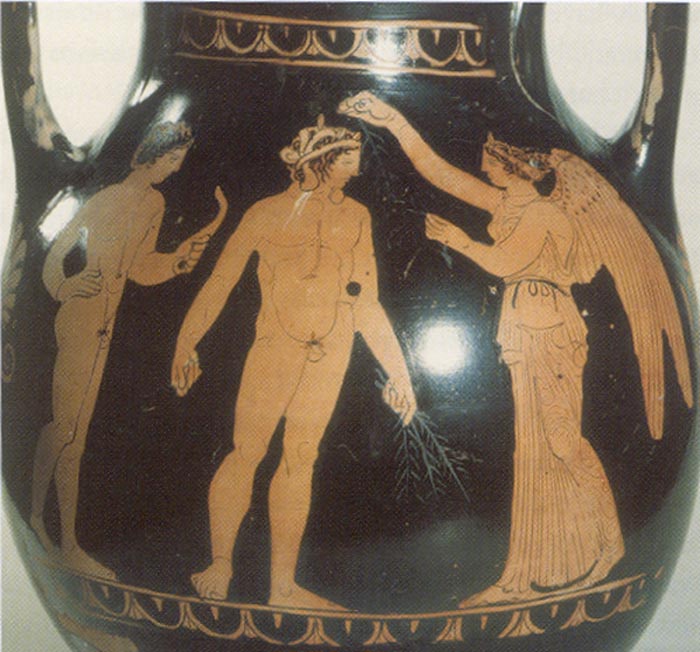

Now: before we resume reading Jaeger, and his discussion of how the aristocratic notion of areté becomes the democratic notion of excellence for ALL the Greeks, let's take a look at some images of Ares, the War God, who personifies courage, war-like or fighting spirit, and manliness.

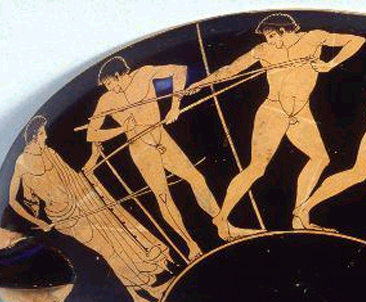

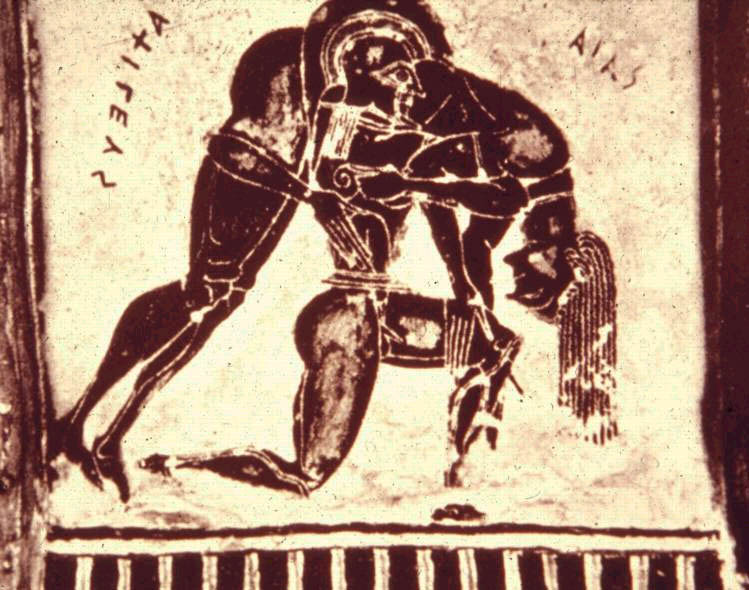

This is from a vase painting:

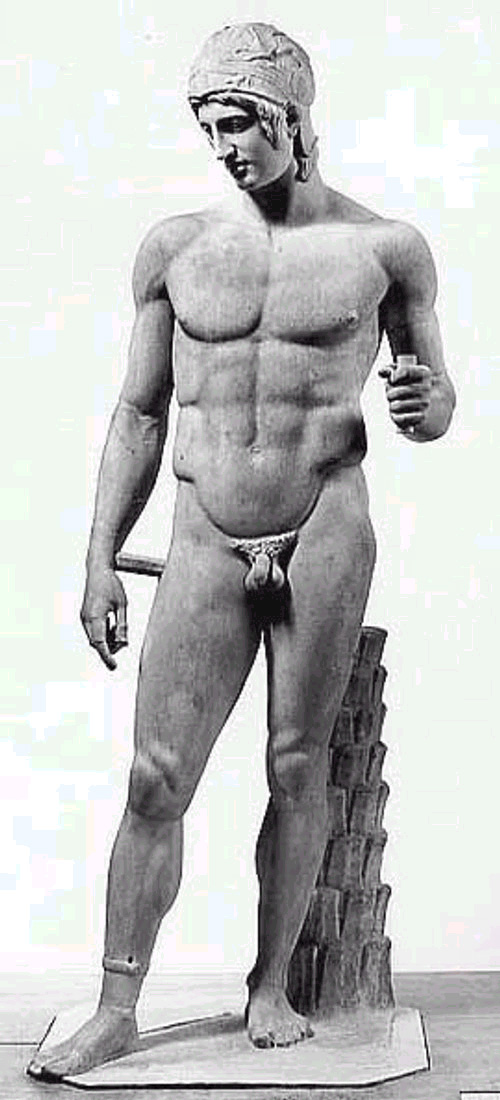

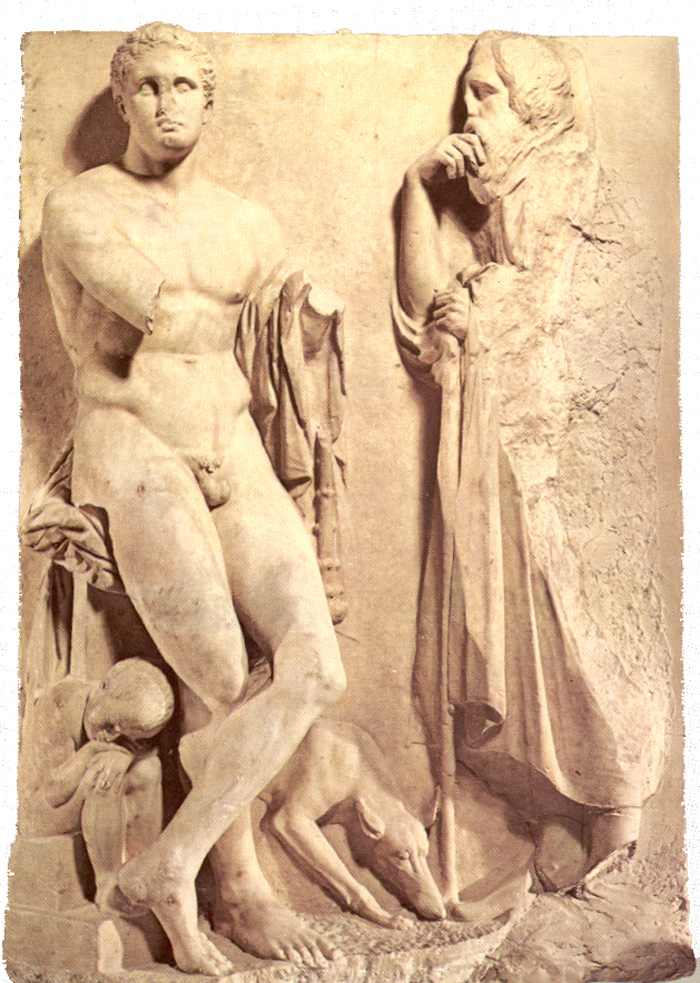

And this is the so-called Borghese Ares -- a Roman copy of a now-lost Greek original attributed to Alkamenes, who lived in the 4th century BC:

This is a head which appears to belong to the "Borghese Ares":

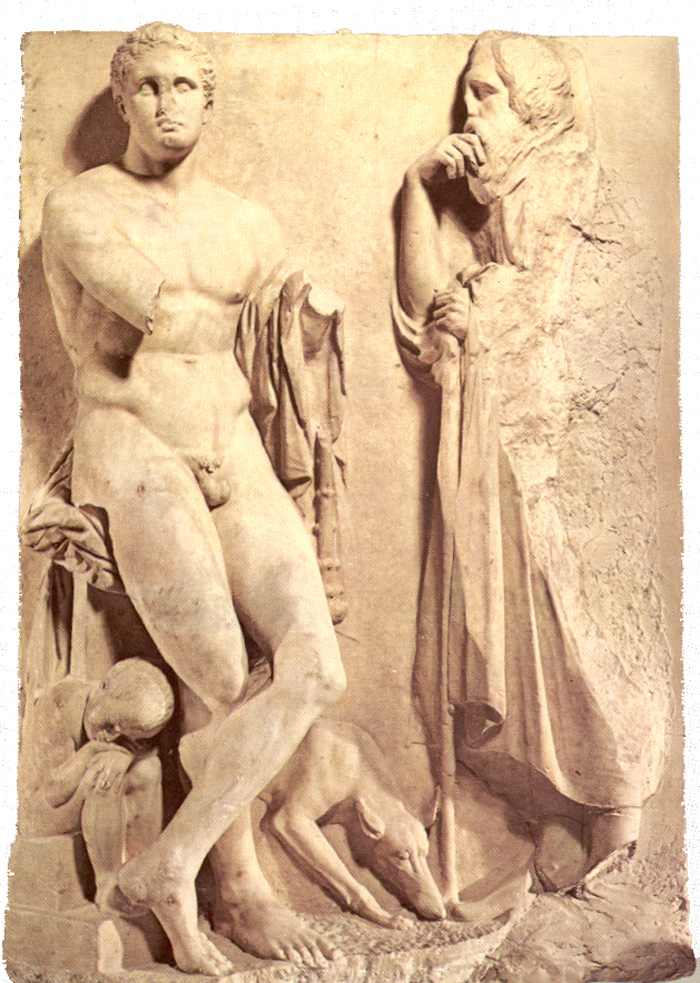

And then there's this, which is really interesting.

It's the so-called Ludovisi Ares, another Roman copy of a Greek original -- the Greek original would have dated from the period of Alexander the Great -- and this Roman copy was dug up in Rome during the Renaissance:

And restored -- the little Eros at the bottom and the hilt of the sword are probably by Bernini.

So what you're seeing is not the original Greek statue, nor the original Roman statue.

What's interesting about it, however, is its size.

Because it appears to be a copy of a much larger work.

In which case it's possible that somewhere in the ancient world there was a temple, like that of Zeus at Olympia, which featured a huge statue of a seated Ares.

It doesn't appear to have been in mainland Greece, because it's not mentioned by Pausanias.

But it could have been in Ionia -- what is today Turkey and Syria -- that's quite possible.

There was in ancient Antioch for example a temple of Apollo, whose statue was said to have been as large as that of Zeus in Olympia.

We don't know, because the temple and statue were destroyed by Christians during the reign of Julian.

Nevertheless, this is another image of Ares:

And you can see that he's a handsome, muscular, athletic, young man.

My guess is that the Roman copies are a tad fleshier than the Greek originals, since the ideal Greek body was "austere and sturdy."

But the copies are close enough.

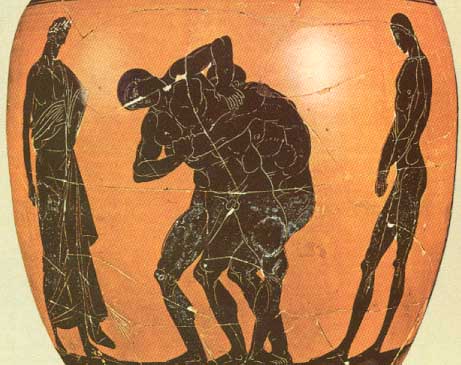

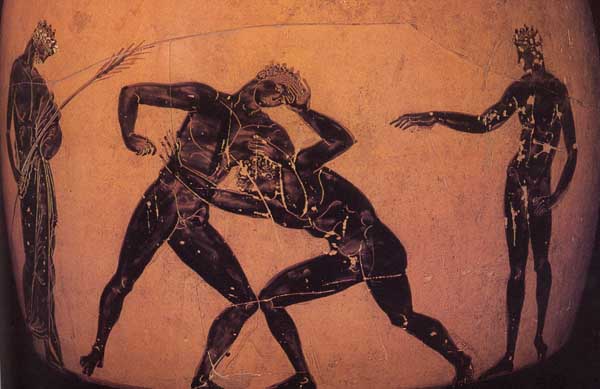

And once again, remember, that these statues would have been modeled upon athletes -- and specifically Fighters: wrestlers, boxers, and pankratiasts.

Because these were, as Jaeger says, Gods in Human Shape.

Gods in Human Shape.

Including Ares -- the Warrior God.

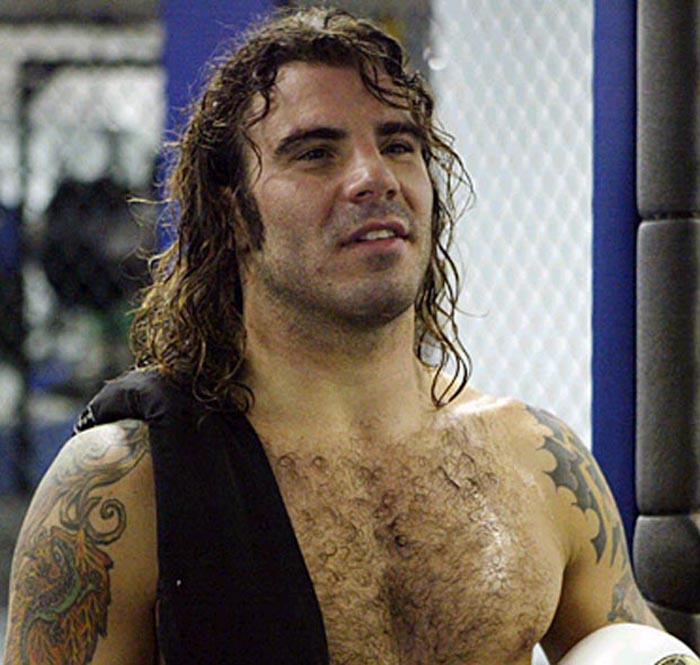

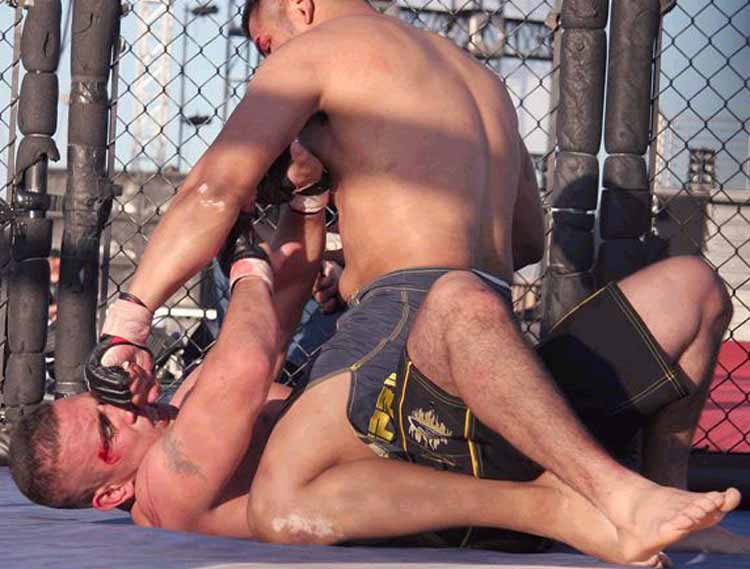

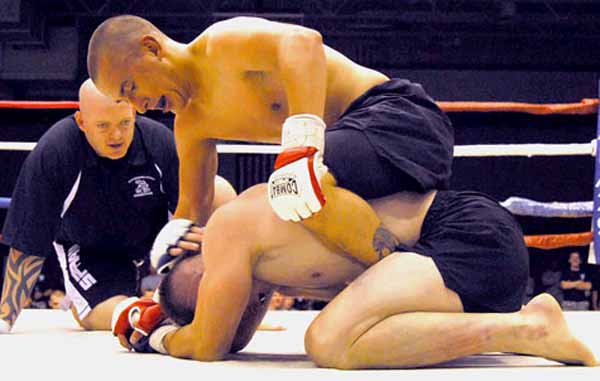

And we can see, when we look at images of present-day pankratiasts -- mixed martial arts fighters -- the resemblance.

And the important thing to remember is that because the Warrior partakes of the manly and fighting qualities of Ares, virtually every depiction of a Warrior is in some measure a depiction of Ares, or at least of his Fighting Spirit.

Fighting Spirit.

It's Fighting Spirit which gives the Warrior, and Men, their Excellence.

It's common, in that regard, for Homer to refer to Warriors as "henchmen of Ares,"

That's in the Lattimore translation and those two phrases are very common.

"Scion" often means a direct descendant, but when, again, we check Liddell, we find the Greek phrase for "scion of Ares" is "ozos Areos"; that OZOS is another one of those core words, meaning in this case "a bough, branch, twig, shoot"; and that ozos is here being used metaphorically as "an offshoot, scion."

So Warriors in general are "offshoots" of Ares.

Ares does have some literal Warrior descendants, including a son, a snake, who's slain by Kadmos, and whose teeth, when sown, grow up to be fully armed men, Warriors, who immediately start fighting and killing each other.

Five of them survive, and become the founding fathers of the five leading families of the Greek city of Thebes.

They and their descendants are known as Spartoi, or "sown men."

And this is what we can call a myth of male parthenogenesis, in which the snake, Ares' son, gives rise to Warriors who are without any female antecedents.

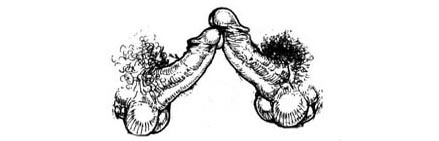

This is a statue of Ares as the god of war and destruction, and you can see that he's holding what appears to be a snake:

And the head of the snake, if that's what it is -- is, appropriately, at the head of the god's penis.

The great Messenian Warrior Aristomenes, who was real, not mythic, and who fought the Spartans for years, was said to have been fathered by a snake.

Presumably a snake who was the son of or otherwise represented Ares.

We can also look at the Homeric Hymn to Ares, in which the god is characterized as

the King of Manliness, the helper of Men, and the giver of dauntless -- that is, fearless -- Youth

So -- it's Ares who puts the War in Warrior, the Fight in Fighter.

And as such we can see that he's the beginning of areté.

That all areté flows from Ares.

It's like Liddell says:

From the same root [ARES] comes areté [excellence] ...the first notion of goodness being that of manhood, bravery in war; cf. Lat. virtus.

And if you can read a little Greek, you'll see that sometimes areté is translated as "excellence," and sometimes as "valour."

For example, in these very important and well-known poems by the seventh-century BC Spartan poet Tyrtaeus, we read

Let each man hold, standing firm, both feet planted on the ground,

biting his lip with his teeth, covering with the belly of his broad

shield his thighs and legs, his chest and shoulders . . let each man,

Closing with the enemy, fighting hand-to-hand with long spear or

sword, wound and take him; and setting foot against foot, and resting

shield against shield, crest against crest, helmet against helmet

let him fight his man chest to chest, grasping the hilt of his sword

or of his long spear.For the man is not brave in war, unless he endure seeing the bloody

slaughter, and standing close reach out for the foe. This is excellence, this is the

best and loveliest prize for the young man to win. A common good this,

for the whole city and all the people, when a man holds, firm-set among the

fighters, unflinchingly.....

"This is excellence," Tyrtaeus says, and the word in Greek is, of course, areté.

And notice that Trytaeus says that such excellence is "a common good ... for the whole city and all the people."

Very important in the history of Greek culture and in the development of both the idea and the ideal of the city-state.

Tyrtaeus, who was, we're told, brought from Athens to Sparta to lead and inspire the Spartans in their desperate struggle against the Messenians, also warns that those who run away in battle -- lose all excellence:

Those who dare to stand fast at one another's side and to advance towards the front ranks in hand-to-hand conflict, they die in fewer numbers and they keep safe the troops behind them;

but when men run away all excellence is lost.

No one could sum up in words each and every evil that befalls a man, if he suffers disgrace. For to pierce a man behind the shoulder blades as he flees in deadly combat is gruesome; and a corpse lying in the dust, with the point of his spear driven through his back from behind, is a shameful sight.

Tyrtaeus then speaks of all the benefits which befall those who either die gloriously in the front ranks, facing the foe, or who survive, equally gloriously, to enjoy a lifetime of acclaim.

And, he concludes,

Let everyone strive now with all his heart to reach the pinnacle of this excellence, with no slackening in war.

Tyrtaeus' words and leadership are credited with helping the Spartans win the Messenian war.

But, as I said, his influence went far beyond Sparta, and lasted for hundreds of years.

For example, four centuries later, an inscription for a fallen Warrior named Timocritus reads,

He fell among the front ranks and left his father with pain beyond measure, but he did not lose sight of his noble [kalos] upbringing. Taking to heart the Spartan declaration of Tyrtaeus, he chose valour [areté] ahead of life.

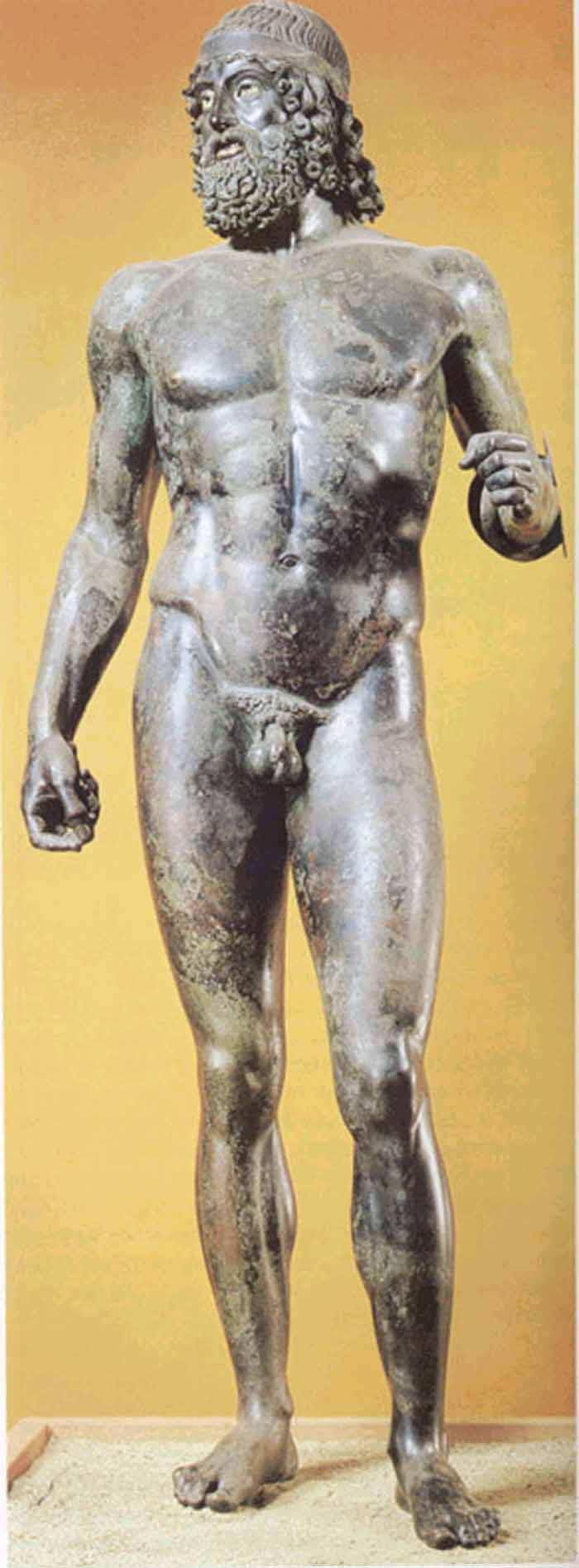

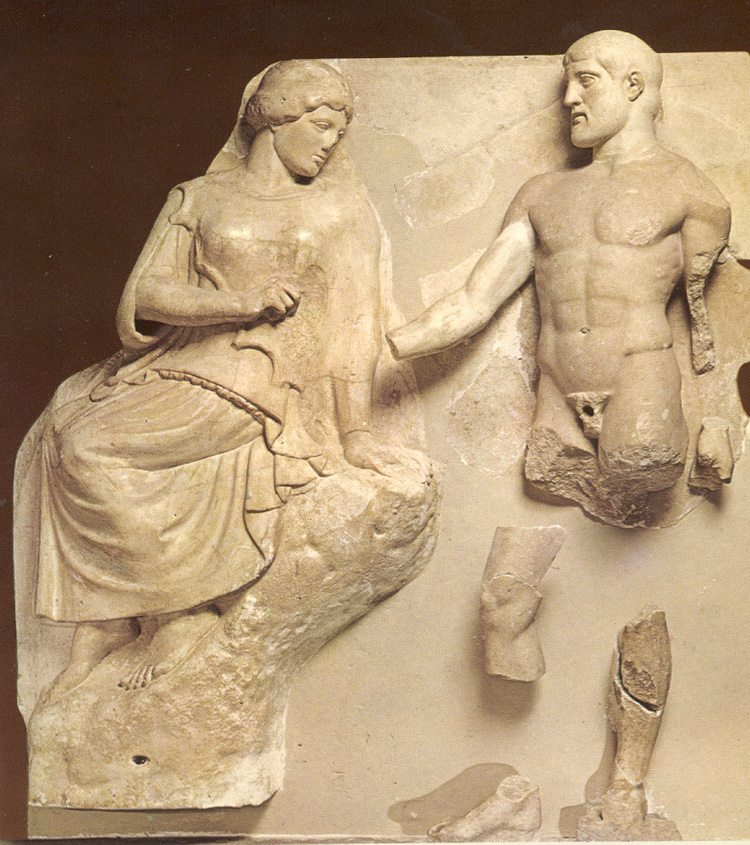

Now, this stele, or grave marker, is not associated with that inscription, but it could be.

We see the grieving father; the fallen Warrior, nude and in all his male glory; and at his feet a weeping boy, perhaps a brother, perhaps a servant -- as well as his faithful dog.

So again, we have the Three Ages of Man:

In Greek, paidas, andras, gerontas -- child, man, elder.

And as you look down the Warrior's body, you see his testicles.

The penis is missing, but the testicles are prominent -- in a natural way.

Once again we return to Liddell:

From the same root [ARES] comes areté [excellence] ...the first notion of goodness being that of manhood, bravery in war; cf. Lat. virtus.

Goodness, Virtus, Areté -- is Manhood.

And we saw in Statius that when the Greeks say Manhood, they're referring both to bravery in war and other metaphorical forms of Manhood, as well as referring explicitly to the male genitals.

The Greek word for genitals is "aidoia."

Which, according to Liddell, derives from "aidoios":

regarded with awe or reverence, august, venerable

So here we are back to Danielou, and the idea of the genitals as sacred.

To the Greeks, the male genitals are to be regarded with reverence and awe, and to be venerated.

And that's one of the reasons they're so openly displayed.

Because they partake of a religious veneration.

The nude male body is venerated.

Venerated because, as Jaeger explains, it expresses the areté of the Warrior.

We talked about that in our discussion of Biton and Kleobis -- that Greek sculpture and painting of the nude male derives its force from the Warrior areté it captures and immortalizes:

Jaeger:

Areté exists in mortal man. Areté is mortal man. But it survives the mortal, and lives on in his glory, in that very ideal of his areté which accompanied and directed him throughout his life.

So when you look at one of these sculptures, you're seeing not just a naked male, but the "very ideal of his areté which accompanied and directed him throughout his life."

Again, that's what gives the sculpture its force.

Again, that's why ancient Greek sculpture has this force, and most subsequent -- that is to say, post-Christian, from the Renaissance forward -- European sculpture of the male nude -- lacks that force.

The Areté of Warriors, which, as we'll discuss again, is also a concomitant of Honour, "survives the mortal, and lives on in their glory, in that very ideal of their areté which accompanied and directed them throughout their lives."

So what you see when you look at these statues of the Argive heroes Biton and Kleobis, is "the ideal of their areté," their excellence

"which accompanied and directed them throughout their lives."

That's what you see in these great works of art:

the areté -- the excellence -- of Men --

and of Man.

And as I said in an earlier post, and as I said above, and as bears repeating:

That's what gives these statues their incredible power.

It's not just that they're naked guys.

In the West, during the Renaissance and afterwards, artists tried to emulate these Greek masterpieces.

And invariably, in my view, failed.

Because they couldn't reproduce or capture the *spiritual* content of these works.

Why?

Because the West had lost what the Greeks had -- the sense of Man as Sacred.

In that sense, not only has the art and culture of ancient Greece never been surpassed -- but it's never been equalled.

And that sense of Man as Sacred, by the way, depends upon -- is ABSOLUTELY DEPENDENT UPON -- a sense of the Genitals as Sacred.

No way around that.

Let's repeat:

The Greek word for genitals is "aidoia."

Which, according to Liddell, derives from "aidoios":

regarded with awe or reverence, august, venerable

The genitals are regarded with awe, reverence.

Must be.

Even when the depiction of the genitals has been damaged, we can see the reverence with which they're regarded.

So -- lose the sense of the genitals as sacred -- and you lose the sense of Man as sacred.

And that loss of the sense of Man as sacred, plays out in many other arenas as well.

For example, during the uproar over the Olympic torch this year, and the attempts to disrupt its progress by pro-Tibetan demonstrators, the New York Times ran an op-ed pointing out that the original, ancient Greek Olympics ran for more than a thousand years, with a just few politically-inspired disruptions -- in all those thousand years.

Whereas the modern-day Olympics, first observed in 1896, have been interrupted by wars and politics repeatedly -- in little over one hundred years.

The author attributed that to the fact that a single ancient Greek city, Elis, "hosted," as we would say, the Games, but otherwise had no strategic or geo-political importance.

Which is more or less true, but it misses the point that the original Greek Games were not just about sport.

They were a religious-athletic event and holiday of immense importance, in which Men, whose display of nude male aggression was, like their genitals, venerated and regarded with awe, came together from all over Greece to compete --

to engage in the Agon, the strenuous physical struggle of one man to overcome another.

That was Sacred to the Greeks.

And they wouldn't disrupt it.

Nor would they let it be disrupted.

People in our time can see that our contemporary Olympics are about politics and nations and ideology -- and therefore are fair game for political protest.

The ancient Greek Olympics -- was about Man.

And the Greek concept of Man.

A concept shared by all the Greeks.

And the Olympics and all the other nude athletic-religious festivals -- were one of the defining characteristices of Greek "civilization" -- of Paidea.

To disrupt the Games wouldn't have simply been an affront to the city of Elis;

it would have been a disowning and disavowal of one's own "Greekness" -- Hellenism.

And no Greek would do that.

It was the Christians, who having consciously and purposefully set out to destroy the Man-centered universe of Greek civilization, disrupted and then destroyed the Olympics and all other athletic festivals.

Because the Christians attacked Man and Man's body.

And under Christianity, the genitals were no longer to be treated with awe and reverence -- but were to be regarded with shame.

But before that happened, there was a thousand years of Greek civilization and paidea -- in which Men like Timocritus, immortalized in that inscription, were taught -- that's the operative word, taught, instructed -- that to strive for Excellence -- was what mattered.

To Strive for Excellence:

Let's look at a few more statements about Excellence from classical Greek authors;

remembering, as I said before, that if you can read a little Greek, you'll see that sometimes areté is translated as "excellence," and sometimes as "virtue," and sometimes as "manliness," and sometimes as "valour."

Because, as with virilis and virtus, they're all the same thing.

For example, in one of his dialogues, Plato says,

For your ancestral house ... has come down to us in tradition as one that is distinguished for beauty, virtue, and whatever is called happiness.~Charmides, 157e

And in the Greek, the word "virtue" is -- areté.

While in this passage about the Ages of Man, Solon, the Athenian lawgiver and poet, says

A boy, while still an immature child, in seven years grows a fence of teeth and loses them for the first time. When the god completes another seven years, he shows the signs of coming puberty. In the third hebdomad, his body is still growing, his chin becomes downy, and the skin changes its hue. In the fourth, everyone is far the best in strength, whereby men show their signs of manliness.

And here, in the Greek, the word for "manliness' is areté.

Then there's the incomparable Pindar.

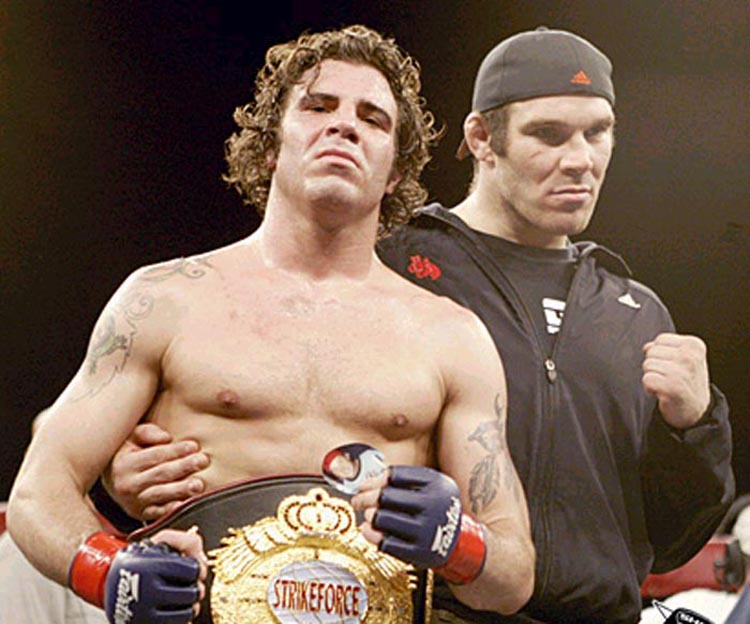

In this exquisite epinikion, or victory song, written for Strepsiadas of Thebes, winner in pankration at the Isthmian games, Pindar says,

But the ancient

splendor sleeps,

and mortals forgetwhat does not attain poetic wisdom's choice pinnacle,

yoked to glorious streams of verses.Therefore celebrate in a sweetly sung hymn

Strepsiadas too, for he is winner of victory at the Isthmos

in the pankration; he is awesome in strength

and handsome to behold,

and his success is no worse than his looks.~ Isthmian 7, translated by Wm Race

And when we look at the original Greek which Professor Race has translated, we see that "success" is actually areté -- which in the Dorian / Lakonian / Spartan dialect Pindar is there using -- is areta.

Now, we'll have a lot more to say about Pindar and areta in AGOGE V.

For now, I just want you to see that Ares and the qualities which come from Ares -- areté aka areta -- are excellence, and virtue, and valour, and manliness, and success in the agon -- the contest.

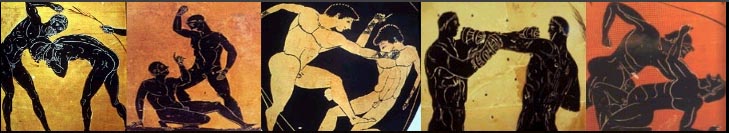

In this case, the most strenuous of all the oh-so-strenuous physical, one-on-one, nude male contests of the Man-centered Greeks:

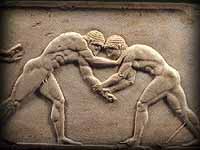

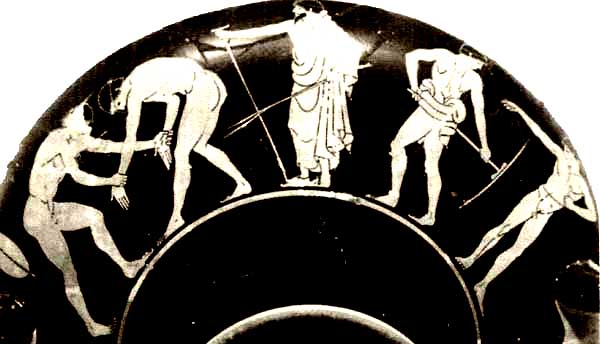

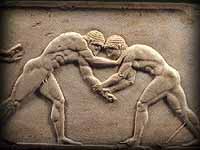

The Pankration:

Strepsiadas too, for he is winner of victory at the Isthmos

in the pankration; he is awesome in strength

and handsome to behold,

and his excellence is no worse than his looks.

"awesome in strength, handsome to behold, and his excellence is no worse then his looks"

Which of course is a thought we encounter in Plato, in the Lysis -- the youthful athlete who is "not less worthy of praise for his goodness than for his beauty."

Now, Pindar continues his praise of Strepsiadas in a decidely Tyrtaean vein, when he turns to Strepsiadas' uncle, who died young and in battle:

[Strepsiadas] is being set ablaze by the violet-haired Muses

and has given a share of his crown to his namesake uncle,

whom Ares of the bronze shield brought to his fated end;

but honor is laid up as a recompense for brave men.

For let him know well, whoever in that cloud of war

defends his dear country from the hailstorm of bloodby turning the onslaught against the opposing army,

that he fosters the greatest glory for his townsmen's race,

both while he lives and after he is dead.

And you, son of Diodotos, as you emulated the warrior

Meleagros and emulated Hektor

and Amphiaraos,

you breathed out your youth in full blossomin the host of fighters at the forefront, where the bravest

bore war's strife with their ultimate hopes.

Remember what Tyrtaeus said about this sort of heroic action, this fighting at the forefront, in war's battle and strife --

This is excellence, this is the

best and loveliest prize for the young man to win. A common good this,

for the whole city and all the people, when a man holds, firm-set among the

fighters, unflinchingly.....

So, again, Pindar is comparing Strepsiadas' excellence in pankration,

awesome in strength

and handsome to behold,

and his excellence is no worse than his looks --

with his uncle's excellence in battle:

you breathed out your youth in full blossom

in the host of fighters at the forefront, where the bravest

bore war's strife with their ultimate hopes.

Agon and Mache --

Contest and Combat --

Nude Contest and Nude Combat --

They're essentially the same deal.

Ares and Agon stand side by side at Olympia and on Olympus.

And I have to point out that in our world, our society, we have professional pankratiasts -- mixed martial artists -- and professional soldiers.

But in Pindar's world, both athletes and soldiers were amateurs.

Unpaid.

They did what they did not for money -- but because they believed in it and wanted to do it.

Their actions were an expression of their striving for areté, areta, excellence.

And, as Redd says in Affirming the masculine, a concept of Men as "at once strong, honorable and beautiful."

So -- the Greeks were taught to continually strive for excellece, for areté.

And, if you'll bear with me, and continue reading, you'll see that to reach for areté in this way is, in the words of Aristotle, "to take possession of the beautiful."

And you'll see that Greek ethical thought is quite consistent in this regard, from Homer -- ca 800 BC -- to Aristotle -- ca 350 BC -- and right down to Julian, who died -- was murdered -- in 363 AD.

Now, before we go on, let's look at two other Greek words which we've seen before, and note how they interact with areté.

Those words are kalos -- meaning both beautiful and noble.

And agathos -- meaning good and worthy and brave.

Homer -- and I'm simplifying a bit -- lived ca 800 BC.

Tyrtaeus, the poet of the Spartan revolution, ca 650 BC.

Pindar, the author of the Victory Songs, ca 450.

And Aristotle ca 350.

But between Tyrtaeus and Pindar there's another poet: Theognis -- who lived ca 550 BC.

Many of his poems are addressed to his "beloved," his boyfriend, Cyrnus.

Like this:

Prefer to live righteously with a few possessions than to become rich by the unjust acquisition of money.

For in justice there is the sum total of every excellence; and every man who is just, Cyrnus, is noble.

~ Theognis, 145-48, translated by Douglas Gerber.

"For in justice there is the sum total of every excellence;

and every man who is just, Cyrnus, is noble."

In the last line, Gerber has translated "agathos" for just;

and "kalos" for noble.

So what we've got is that Justice is the sum total of all Excellence -- areté;

and that every man who is good, brave, and worthy -- is noble and beautiful.

How's that for an ethical ideal?

That in Justice is found Excellence -- and that the good, brave, and worthy man -- is also noble and beautiful.

As an ethical ideal -- you could do a lot worse.

And since abandoning the Greeks -- and Man -- men often have.

Which brings us to Part II :

Let's get back to Jaeger.

Having set before us, in his introduction, the great anthropocentric -- that is, Man-centered -- educational purpose of Greek Paideia, Jaeger then turns to a discussion of the relationship between the Homeric ideas of areté or excellence -- and honor.

Homer was the Bible of the Greeks -- no question of that.

And for more that a thousand years, Homer, his Heroes, and their pristine world of flesh and spirit, occupied the very center of Greek culture.

Everything flowed from Homer.

So it's important for us to understand what the Homeric Hero is about.

And what he was about -- was Excellence and Honor.

I've already written about this, in talking about the Homeric hero Ajax.

And I'm going to begin here by recapitulating some of that discussion from an attack on men being together.

And then move forward with Jaeger as he talks about how the Homeric idea of excellence was transformed into the Hellenic ideal of excellence.

Here's Jaeger talking about the Homeric concept of Honour -- he uses the British spelling, so I will too:

We can find a more natural clue to the history of Greek culture in the history of the idea of areté, which goes back to the earliest times. There is no complete equivalent for the word areté in modern English; its oldest meaning is a combination of proud and courtly morality with warlike valour. But the idea of areté is the quintessence of early Greek aristocratic education.

An essential concomitant of areté is honour. In a primitive community, it is inseparable from merit and ability.

So -- Jaeger begins by talking about "areté."

And again, the important thing to remember about "areté," is that over time, the word and the concept becomes a gift from the Greek aristocracy to ALL of Greek culture.

So areté does not remain the property of the aristocracy alone.

Rather, this idea, which combines excellence and courage and idealism and valour, comes to belong to all of the Hellenes -- all of the Greek-speaking peoples.

And note what Jaeger says:

"An essential concomitant of areté is honour. In a primitive community, it is inseparable from merit and ability."

Honour.

Honour is "an essential concomitant of areté," and "is inseparable from merit and ability."

To paraphrase:

Honour is an essential concomitant of warrior excellence, and is inseparable from merit and ability.

Jaeger:

The philosophy of later times bade man obey an inner standard; it taught him to regard honour as the external image of his internal value, reflected in the criticism of his fellows.

...

Homer and the aristocracy of his time believed that the denial of honour due was the greatest of human tragedies. The heroes treat each other with constant respect, since their whole social system depends on such respect. They have all an insatiable thirst for honour, a thirst which is itself a moral quality of individual heroes. When the Homeric man does a great deed, he never hesitates to claim the honour which is its fit reward.

,,,

Christian sentiment will regard any claim to honour, any self-advancement, as an expression of sinful vanity. The Greeks, however, believed such ambition to be the aspiration of the individual towards that ideal and supra-personal sphere in which alone he can have real value. Thus it is true in some sense to say that the areté of a hero is completed only in his death. Areté exists in mortal man. Areté is mortal man. But it survives the mortal, and lives on in his glory, in that very ideal of his areté which accompanied and directed him throughout his life.

So look at what Jaeger says:

Honour is "the external image of a man's internal value, reflected in the criticism of his fellows."

Honour then is a reflection of the man's internal value, expressed as a communal value.

Remember what my foreign friend says in Natural Masculinity and Phallic Bonding: the masculinity of men flows from the male group.

And remember what the Greek language tells us:

- eu = good; andros = man; eu-andros, says Liddell, means "abounding in good men and true";

- while eu-andria means abundance of men, thus manhood, manliness, courage, spirit.

Honour is a masculine value which exists, usually, within a group context.

Jaeger speaks of "criticism" -- to which I would add "praise":

Honour is "the external image of a man's internal value, reflected in the criticism and praise of his fellows."

Jaeger:

Honour means that "the heroes treat each other with constant respect, since their whole social system depends on such respect."

Honour breeds respect -- respect breeds honour.

And, to the Homeric Greeks, "the denial of honour due was the greatest of human tragedies."

That's what happened to Ajax -- as again, I discussed in the Ledger message thread and which I'll discuss again here.

So: Not in the Iliad, but in what's known as the Epic Cycle, which tells the entire story of the Trojan War, we learn that after Achilles is killed, Ajax fights hardest to save his body and return it to the Greek camp.

And Ajax is well-equipped to do that.

Because after Achilles, he's the mightiest Warrior in the Greek army.

In addition, Ajax is Achilles' cousin.

After rescuing the body -- which again is a point of honour -- Ajax asks that he be given Achilles' armour, which was created by the god Hephaistos.

But Odysseus too asks for the armour.

This creates a dilemma for the Greek leadership, since it needs the services of both men.

There are at least two different versions of the story, but ultimately and in both, the armour is awarded to Odysseus -- who's clearly less deserving of it.

Ajax is infuriated.

And after slaughtering some sheep, which the goddess Athena has led him to think are Greek soldiers, he kills himself.

Why does he kill himself?

Because he's been denied Honour -- which he deserved.

And, as Jaeger says, to the Homeric Greeks, "the denial of honour due was the greatest of human tragedies."

Now, I brought this up in the Ledger thread because, in an article in the NY Times which looked at homicides and fatal accidents among US veterans of the war in Iraq, the Times said that

In an online course for health professionals, Capt. William P. Nash, the combat/operational stress control coordinator for the Marines, reaches back to Sophocles' account of Ajax, who slipped into a depression after the Trojan War, slaughtered a flock of sheep in a crazed state and then fell on his own sword.

Is that accurate?

NO.

Though no doubt well intended, does it make sense for someone like Capt. Nash to attempt to apply contemporary concepts about depression and post-traumatic stress disorder to an ancient Warrior like Ajax?

NO.

Ignoring for the moment that what happened to Ajax occurred not "after," as Nash would have it, but *during* the Trojan War --

Ajax isn't suffering from flashbacks, he's not concerned about the number of civilians he's killed -- nothing like that.

To someone like Ajax, the point of the war is to retrieve Helen, who's been taken from her husband, and to kill and enslave as many Trojans and their allies as possible --

while covering himself in glory.

Glory.

Let's apply to that Jaeger's formulation:

Honour is "the external image of a man's internal value, reflected in the criticism and praise of his fellows."

Ajax becomes upset when his fellow Warriors, who share his value system, deny him an Honour which is clearly his due.

That's his tragedy.

He can't get past it.

It's similar to what happens to Achilles, from whom Agamemnon unjustly and dishonorably takes a slave-girl.

Achilles can't get past that, and his anger at honour denied leads eventually to Patroclus' death -- and Achilles' own death.

So what happens to both Achilles and Ajax happens within the context of their own value system.

And to "deconstruct" Ajax, who, again, is one of the great Warrior heroes of the Iliad, and claim that he suffers from some contemporary version of depression or PTSD --

when in reality what afflicts him is "the denial of honour due":

to deconstruct Ajax in that way is to not so subtly deconstruct the entire Masculine code of Honour --

a code which boys learned for more than a millenium in the ancient world -- and then again in the modern world following the Renaissance.

Again, in the Iliad, it's Glaukos, Sarpedon's fellow countryman and beloved companion, who makes a famous statement of the Homeric Warrior creed of areté -- which is dependent upon Honour:

to strive always for the highest excellence, and to excel all others

~ Iliad VI, 208

Jaeger notes that that creed used to be taught to every schoolboy;

at least every schoolboy who learned Greek;

but that now -- and he's writing in 1935 -- "modern educational 'levellers' have ... abandoned" it.

And that's very serious.

When you deny boys their natural urge to compete and excel -- to compete and excel among their fellows -- you do them great damage.

Because, says Jaeger, the desire, the thirst, for Honour, "is itself a moral quality of individual heroes";

while the "ambition" to Honour is "the aspiration of the individual towards that ideal and supra-personal sphere in which alone he can have real value."

Honour is a *moral* quality and an aspiration towards the ideal.

An ideal and "supra-personal" -- more than and above personal -- "sphere in which alone he can have real value."

So -- the claim to Honour, the claim to excellence, is for the Greeks, the aspiring of the individual to an ideal and more than personal sphere -- and only there can he have real value.

Translation:

Honour -- Honour among Men -- matters -- a lot!

To the Group -- and to the Individual.

Can the concept of Honour be peverted -- into what we might call "social" or "pseudo-honour?"

Sure.

But so long as the concept of Honour works to encourage "great deeds" -- deeds which are great because they're morally worthy, involve both great danger and great prowess, and require, as we'll see, self-sacrifice -- it's to the benefit of both the individual Man and the male group.

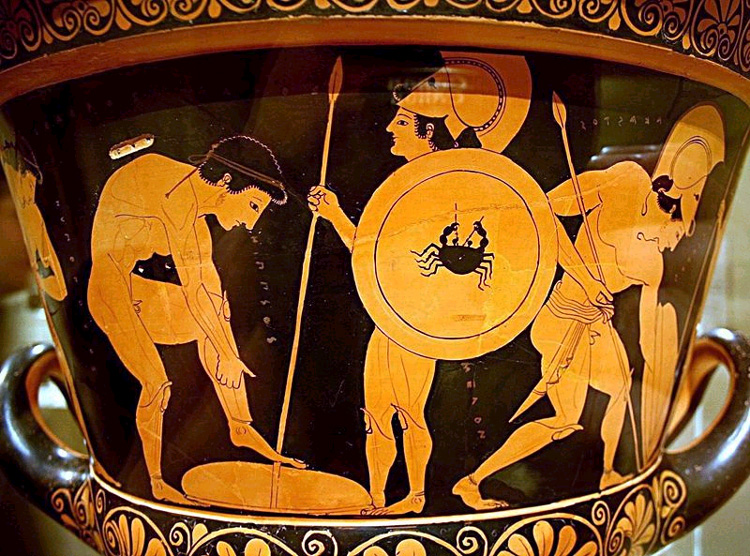

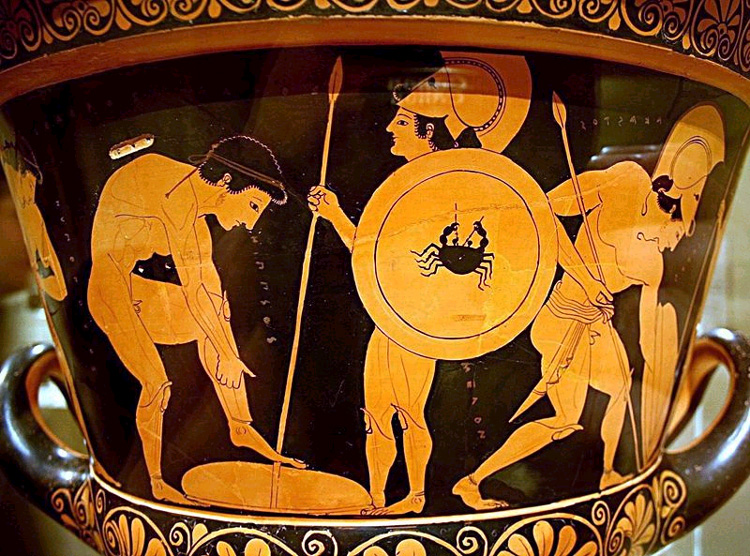

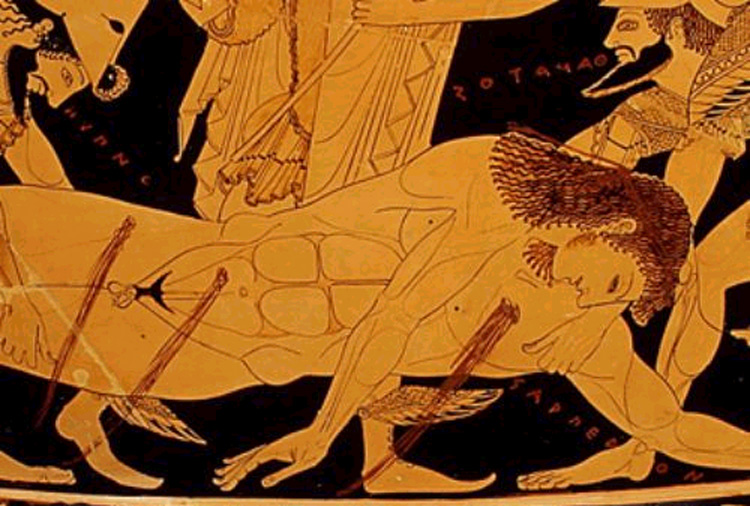

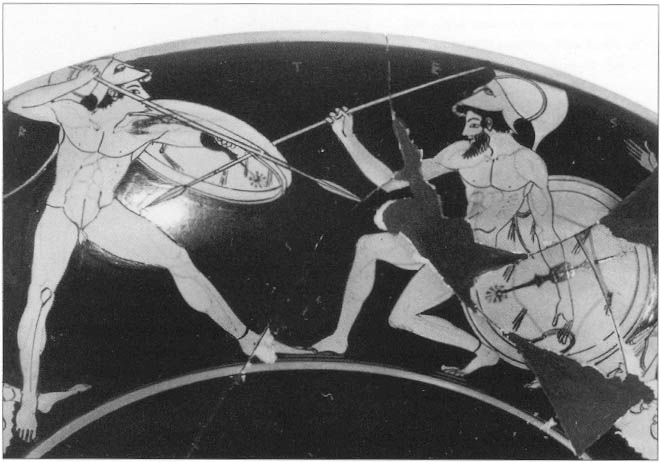

So -- if we look at two vase paintings by Euphronios, which depict two scenes from the Iliad -- the first the arming of Warriors; and the second the aftermath of the death of Lykian hero and Trojan ally Sarpedon -- here's what we see:

Warriors Arming

These guys are, in Greek terms, both Beautiful and Brave.

And, following a Warrior Code of Honour, they'll go into battle determined to "to strive always for the highest excellence, and to excel all others."

That's what we see them preparing to do.

They put on their armour -- but leave their genitals exposed.

They'll fight honorably.

As Men.

Naked and unashamed.

And with respect for their foe.

And if they die, they'll die -- honorably.

And as Men.

The dead Sarpedon being taken by Sleep and Death to Hades

Sarpedon has fought bravely.

He's been defeated and killed.

But the Greeks respect him.

And he's depicted, even in death, as Beautiful and Brave, and worthy of the gods' attention.

Now notice, as is always true for the Greeks, that while areté and honour may flow from the commune or group, they're about the individual.

Just as the agon, the athletic contest, is about ONE Man's strenuous physical struggle to overcome another --

So, on the Homeric battlefield, generally speaking, ONE Warrior faces Another.

In war as in athletics, it's one on one.

And ideally, it's a contest of two equally-noble beings.

As is FROT.

Ideally.

Remember that I said earlier in this thread that the Greek idea of Beauty contains within it the idea of nobility.

The Beautiful and the Brave.

For the Greeks, Beauty is only Beautiful -- if it's Brave.

That's the difference between looking at a pic of a male model;

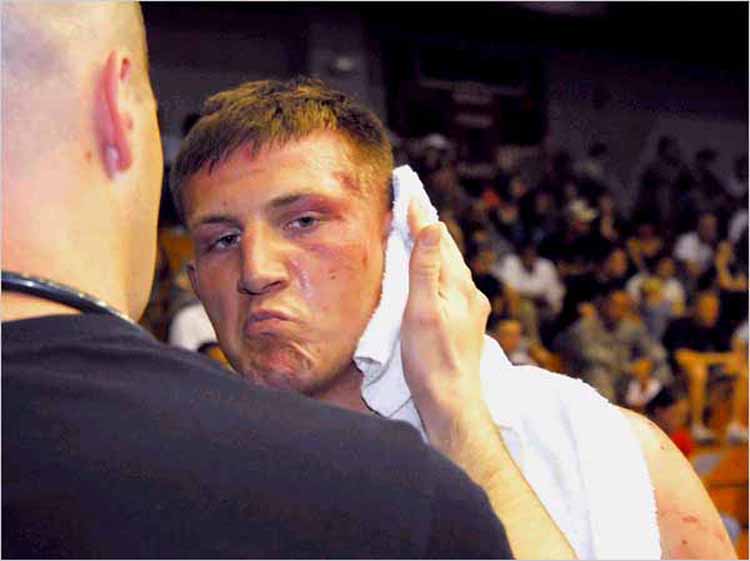

and of a pic of fighters fighting:

The fighters are exhibiting a BRAVE BEAUTY.

Which is the only TRUE BEAUTY.

Brave Beauty is True Beauty.

And it's honorable.

Indeed, in the Oxford Classical Greek Dictionary, when you look up the word "honour," the first entry you see is -- kalos -- the word for beautiful.

These ideas -- that beauty can be and should be honorable and honor beautiful -- are not easy for us.

Yet they're core ideas for the Greeks.

Brave Beauty is True Beauty.

And it's honorable.

Which can be expressed in this way:

Brave Beauty is Beauty rendered Honorable by Aggression.

That's an idea, I know, which will drive most feminists, effeminists, analists, and pansexualists, insane.

It will make them rage.

It's an idea which someone like "gay Episcopalian" will never accept.

Too bad.

Beauty, Bravery, Honour -- all are related to and linked with Aggression.

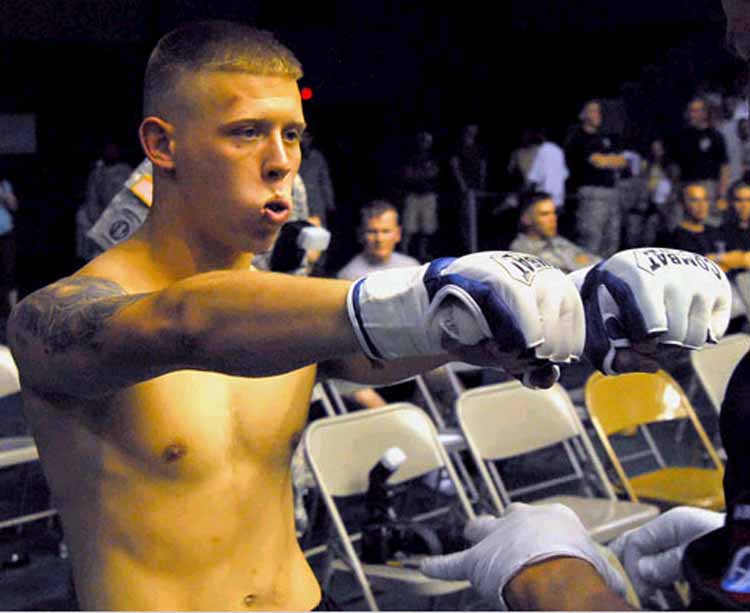

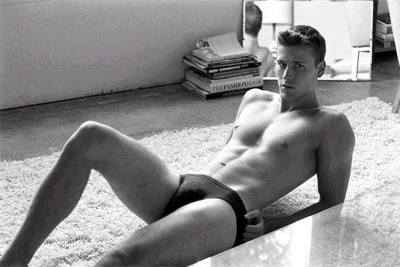

So, if we look again at some pictures --

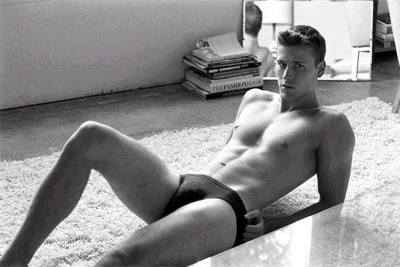

Here's the model:

And here's a UFC fighter at the beginning of a bout:

To me, the Fighter exhibits a Brave Beauty.

The model does not.

The Fighter demonstrates what NW has spoken of: aggression and the beauty of guys who assert that aggression.

As I've said before, NW's concept of the "beauty of guys" is far closer to that of the Ancient Greeks -- than it is to our modern concept of beauty -- which tends, ultimately, to be effete.

The Greek concept says that true Beauty contains the Brave, true Beauty contains the Noble -- and the Good.

In that sense, True Beauty is Honorable.

Now, once again, let me caution that I don't know the individuals depicted in these pictures.

What I've been told is that there's a huge amount of money connected with the UFC these days.

And that's not good.

Because money corrupts.

Nonetheless, I think it's fair to say that the guys who fight in these bouts are displaying a Brave Beauty.

They may not conform to the Greek Ideal -- in many ways.

But the Brave Beauty -- is there.

So, and once again:

Beauty, Bravery, Honour -- all are related to and linked with Aggression.

And Honour -- matters.

Because Honour flows from Honour.

So that it matters, as one of our Warriors said years ago, whether you Honor The Phallus.

And it's not surprising therefore, in a society like our own, which dishonors honour -- that phallus too is dishonored, and turned away from.

And that sex ceases to be about genitals.

And that sex ceases to be honorable.

That in the gay male/analist community, where both honor and phallus are most DIS-honored, sex no longer has any connection to morality;

while barebacking and gift-giving -- the purposeful infection by one human being of another with a fatal disease -- is ACCEPTED as an inescapable fact of life -- and death.

And that's why I'm talking about these ancient Greek concepts of Excellence and Beauty and Nobility and Good -- all of which derive from Man's Willingness to Fight -- on this site which is obstensibly about a sexual act.

Because no sexual act can be divorced from the moral context in which it occurs.

And no sexual choice can be understood apart from the moral context in which it is made.

Whether we care to admit so or not, our decisions about sex and our choices about sex are moral decisions and moral choices.

They do not occur, as the pansexualists would have you believe, in a universe devoid of morality.

Frot, we've often said, is about innocence and joy.

Anal penetration about pain and death.

That much is obvious.

Frot, we've also said, is about Masculine Rigor.

While anal is part and parcel of an effeminized and sloppy hedonism.

That too is obvious.

Frot celebrates and exalts Man as Man and Man to Man.

Anal denies and destroys Manhood.

Frot, as Frances has said, is "natural and organic."

Anal is UNnatural, and plunges its actors into a nightmare realm of the inorganic, artificial and false.

So: the sexual "life-choices" which we make are reflections of our Lives.

Do we choose to live in an amoral universe -- an immoral universe -- or a moral universe?

Do we strive, in all aspects of our life, for Excellence --

and for the Honor which, as Jaeger says, is "an essential concomitant of excellence?"

Do we strive for Excellence and Honor?

Or for mediocrity and shame?

For nothing.

The Greeks lived better than do we.

They LIVED better than we do.

They lived BETTER than we do.

No one looking at their art, or reading their poetry, their philosophy, their history, their myth -- all Greek words by the way -- can conclude otherwise.

So again the question is -- how do we want to live?

How do YOU want to live?

So many males, before, during, and now "after" AIDS, so many gay-identified males that I knew lived lives that were about the pursuit of pleasure and the pursuit of their selfish pleasure alone.

There was nothing of them about honor, and certainly not about excellence.

Yes, many sought to have "a good body."

But that's not Excellence.

Excellence -- Areté -- derives from ARES.

And Ares from contest and battle, war and strife.

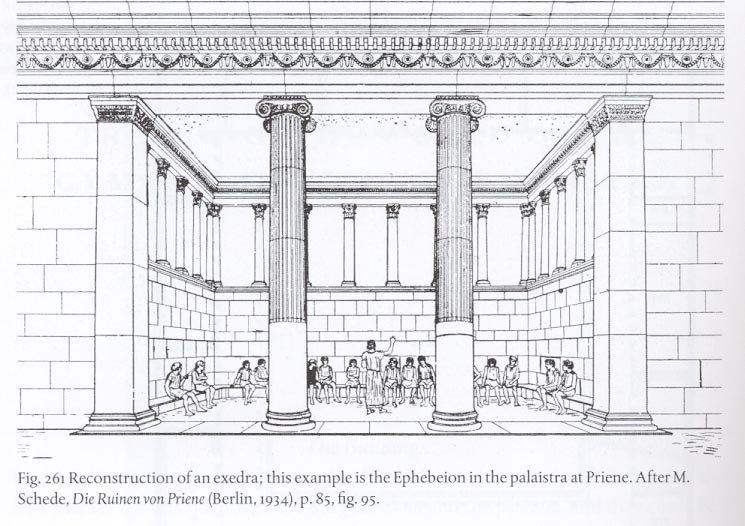

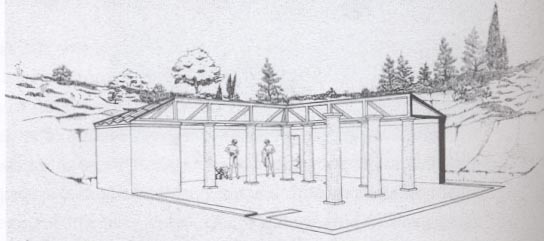

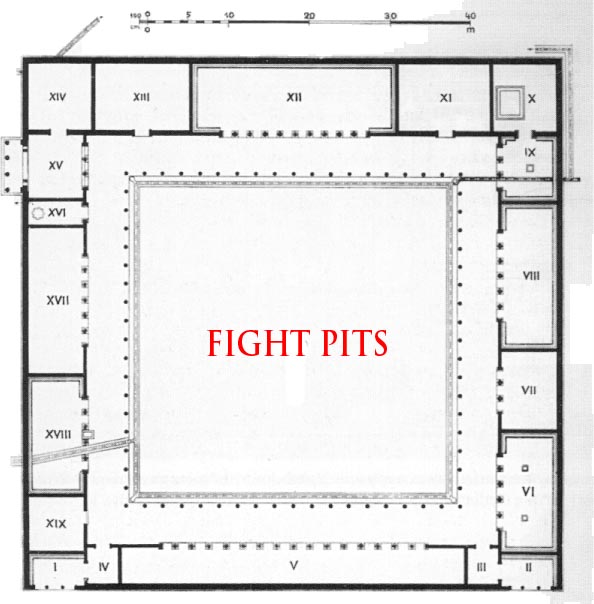

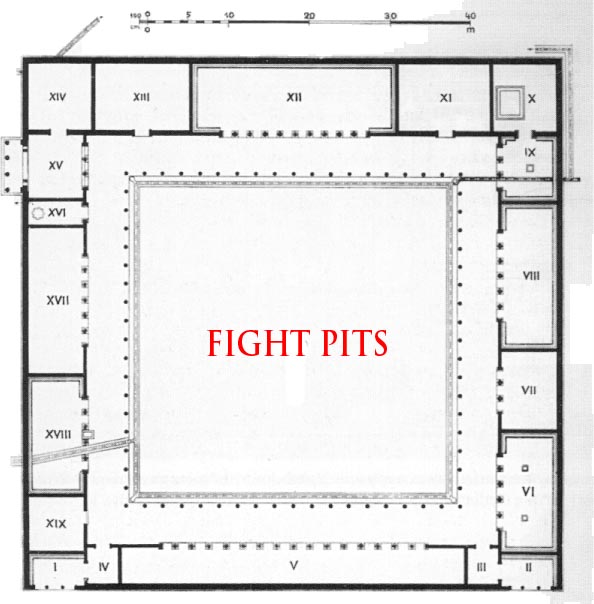

What, according to Pausanias, the Spartan law-giver Lykourgos called "ten machen ton ephebon" -- the fighting of the youths.

The Fighting of the Youths.

From the same root [ARES] comes areté [excellence] ...the first notion of goodness being that of manhood, bravery in war; cf. Lat. virtus.

Manhood, Bravery in War, Goodness.

Let's close this section on Honor by re-capping Jaeger's discussion of both Honor and Areté.

We can find a more natural clue to the history of Greek culture in the history of the idea of areté, which goes back to the earliest times. There is no complete equivalent for the word areté in modern English; its oldest meaning is a combination of proud and courtly morality with warlike valour. But the idea of areté is the quintessence of early Greek aristocratic education.

An essential concomitant of areté is honour. In a primitive community, it is inseparable from merit and ability.

...

The philosophy of later times bade man obey an inner standard; it taught him to regard honour as the external image of his internal value, reflected in the criticism of his fellows.

...

Homer and the aristocracy of his time believed that the denial of honour due was the greatest of human tragedies. The heroes treat each other with constant respect, since their whole social system depends on such respect. They have all an insatiable thirst for honour, a thirst which is itself a moral quality of individual heroes. When the Homeric man does a great deed, he never hesitates to claim the honour which is its fit reward.

...

Christian sentiment will regard any claim to honour, any self-advancement, as an expression of sinful vanity. The Greeks, however, believed such ambition to be the aspiration of the individual towards that ideal and supra-personal sphere in which alone he can have real value. Thus it is true in some sense to say that the areté of a hero is completed only in his death. Areté exists in mortal man. Areté is mortal man. But it survives the mortal, and lives on in his glory, in that very ideal of his areté which accompanied and directed him throughout his life.

The gods themselves claim their due honour. They jealously avenge any infringement of it, and pride themselves on the praise which their worshippers give to their deeds. Homer's gods are an immortal aristocracy. And the essence of Greek worship and piety lay in giving honour to godhead: to be pious is 'to honour the divinity'. To honour both gods and men for their areté is a primitive instinct.

On this basis, we can comprehend the tragic conflict of Achilles in the Iliad. His indignation at his comrades and his refusal to help them do not spring from an exaggerated individual ambition. A great ambition is, for Greek sentiment, the quality of a great hero. When the hero's honour is offended, the very foundations of the alliance of the Achaean warriors against Troy are shaken. The man who infringes another's honour ends by losing sight of true areté itself. Such a difficulty would now be mitigated by feelings of patriotism; but patriotism is strange to the old aristocratic world. Agamemnon can only make a despotic appeal to his own sovereign power; and such an appeal is equally foreign to aristocratic sentiment, which recognises the leader only as primus inter pares. Achilles, when he is refused the honour which he has earned, feels that he is an aristocrat confronted by a despot. But that is not the chief issue. The head and front of the offence is that a pre-eminent areté has been denied its honour. The death of Ajax, the mightiest Greek hero after Achilles, is the second great tragedy of offended honour. The weapons of the dead Achilles are awarded to Odysseus, although Ajax has done more to earn them. The tragedy of Ajax ends in madness and death; the wrath of Achilles brings the Greek army to the edge of the abyss.

Homer can scarcely say whether it is possible to repair honour once it has been injured. Phoenix advises Achilles not to bend the bow too far, and to accept Agamemnon's gift as an atonement -- for the sake of his comrades in their affliction. But it is not only from obstinacy that Achilles in the original saga refuses the offers of atonement: as is shown once more by the parallel example of Ajax, who returns no answer to the sympathetic words of his former enemy Odysseus when they meet in the underworld, but silently turns away 'to the other souls, into the dark kingdom of the dead'.

[The goddess] Thetis [, Achilles' mother,] entreats Zeus thus: 'Honour my son, who must die sooner than all others. Agamemnon has robbed him of his honour; do you honour him, Olympian!' And the highest of the gods is gracious to Achilles, by allowing the Achaeans, deprived of his help, to be defeated; so that they see how unjustly they have acted in cheating their greatest hero of his honour.

Having discussed areté and honor among the Homeric Greeks, Jaeger then describes how the Homeric idea of areté became the Hellenic ideal of areté -- in a sequence which moves from Homer through Pindar and Plato to Aristotle:

In later ages, love of honour was not considered as a merit by the Greeks: it came to correspond to ambition as we know it. But even in the age of democracy we can see that love of honour was often held to be justifiable in the intercourse of both individuals and states. We can best understand the moral nobility of this idea by considering Aristotle's description of the megalopsychos, the proud or high-minded man. In many details, the ethical doctrines of Plato and Aristotle were founded on the aristocratic morality of early Greece: in fact, there is much need for a historical investigation (from that point of view) of the origin, development, and transmission of the ideas which we know as Platonic and Aristotelian. The class limitations of the old ideals were removed when they were sublimated and universalised by philosophy: while their permanent truth and their indestructible ideality were confirmed and strengthened by that process. Of course the thought of the fourth century is more highly detailed and elaborated than that of Homeric times. We cannot expect to find its ideas, or even their exact equivalents, in Homer. But in many respects Aristotle, like the Greeks of all ages, has his gaze fixed on Homer's characters, and he develops his ideals after the heroic patterns. That is enough to show that he was far better able to understand early Greek ideas than we are.

It is initially surprising for us to find that pride or high- mindedness is considered as a virtue. And it is also notable that Aristotle does not believe it to be an independent virtue like the others, but one which presupposes them and is 'in a way an ornament to them'. We cannot understand this unless we recognise that Aristotle is here trying to assign the correct place in his analysis of the moral consciousness to the high-minded areté of old aristocratic morality. In another connexion he says that he considers Achilles and Ajax to be the ideal patterns of this quality. High-mindedness is in itself morally worthless, and even ridiculous, unless it is backed by full areté, the highest unity of all excellences, which neither Aristotle nor Plato shrinks from describing as kalokagathia.

["Kalokagathia," a word which combines "kalos" and "agathos," is most simply defined as "nobility and goodness" -- remembering that "kalos" means both beautiful and noble; and "agathos" both brave and good.]

The great Athenian thinkers bear witness to the aristocratic origin of their philosophy, by holding that areté cannot reach true perfection except in the high-minded man. Both Aristotle and Homer justify their belief that high-mindedness is the finest expression of spiritual and moral personality, by basing it on areté as worthy of honour. 'For honour is the prize of areté; it is the tribute paid to men of ability.' Hence pride is an enhancement of areté. But it is also laid down that to attain true pride, true magnanimity is the most difficult of all human tasks.

Here, then, we can grasp the vital significance of early aristocratic morality for the shaping of the Greek character. It is immediately clear that the Greek conception of man and his areté developed along an unbroken line throughout Greek history. Although it was transformed and enriched in succeeding centuries, it retained the shape which it had taken in the moral code of the nobility. The aristocratic character of the Greek ideal of culture was always based on this conception of areté.

Under the guidance of Aristotle, we may here investigate some of its further implications. He explains that human effort after complete areté is the product of an ennobled self-love, psi i lantia. This doctrine is not a mere caprice of abstract speculation -- if it were, it would be misleading to compare it with early conceptions of areté. Aristotle is defending the ideal of fully justified self-love as against the current beliefs of his own enlightened and 'altruistic' age; and in doing so he has laid bare one of the foundations of Greek ethical thought. In fact, he admires self-love, just as he prizes high-mindedness and the desire for honour, because his philosophy is deeply rooted in the old aristocratic code of morality. We must understand that the Self is not the physical self, but the ideal which inspires us, the ideal which every nobleman strives to realise in his own life. If we grasp that, we shall see that it is the highest kind of love which makes man reach out towards the highest areté: through which he 'takes possession of the beautiful'.

The last phrase is so entirely Greek that it is hard to translate. For the Greeks, beauty meant nobility also. To lay claim to the beautiful, to take possession of it, means to overlook no opportunity of winning the prize of the highest areté.

But what did Aristotle mean by the beautiful? Our thoughts turn at once to the sophisticated views of later ages -- the cult of the individual, the humanism of the eighteenth century, with its aspirations towards aesthetic and spiritual self-development. But Aristotle's own words are quite clear. They show that he was thinking chiefly of acts of moral heroism. A man who loves himself will (he thought) always be ready to sacrifice himself for his friends or his country, to abandon possessions and honours in order to 'take possession of the beautiful'. The strange phrase is repeated: and we can now see why Aristotle should think that the utmost sacrifice to an ideal is a proof of a highly developed self-love. 'For,' he says, 'such a man would prefer short intense pleasures to long quiet ones; would choose to live nobly for a year rather than to pass many years of ordinary life; would rather do one great and noble deed than many small ones.'

These sentences reveal the very heart of the Greek view of life -- the sense of heroism through which we feel them most closely akin to ourselves. By this clue we can understand the whole of Hellenic history -- it is the psychological explanation of the short but glorious aristeia of the Greek spirit. The basic motive of Greek areté is contained in the words 'to take possession of the beautiful'. The courage of a Homeric nobleman is superior to a mad berserk contempt of death in this -- that he subordinates his physical self to the demands of a higher aim, the beautiful. And so the man who gives up his life to win the beautiful, will find that his natural instinct for self-assertion finds its highest expression in self-sacrifice. The speech of Diotima in Plato's Symposium draws a parallel between the struggles of law-giver and poet to build their spiritual monuments, and the willingness of the great heroes of antiquity to sacrifice their all and to bear hardship, struggle, and death, in order to win the prize of imperishable fame. Both these efforts are explained in the speech as examples of the powerful instinct which drives mortal man to wish for self-perpetuation. That instinct is described as the metaphysical ground of the paradoxes of human ambition.

Aristotle himself wrote a hymn to the immortal areté of his friend Hermias, the prince of Atarneus, who died to keep faith with his philosophical and moral ideals; and in that hymn he expressly connects his own philosophical conception of areté with that found in Homer, and with its Homeric ideals Achilles and Ajax. And it is clear that many features in his description of self-love are drawn from the character of Achilles. The Homeric poems and the great Athenian philosphers are bound together by the continuing life of the Hellenic ideal of areté.

So: What have we got?

"the utmost sacrifice to an ideal is a proof of a highly developed self-love."

"Kalos" -- meaning both beautiful and noble; and "agathos" -- meaning both brave and good -- joined in the single concept of "Kalokagathia": nobility and goodness.

Which is "full areté, the highest unity of all excellences."

And, according to Aristotle, "to take possession of the beautiful" means to engage in acts of *moral* heroism.

That moral heroism is in opposition and has ALWAYS been in opposition to hedonism -- of this age or any other age.

The Spartans at Thermopylae were an expression of moral heroism.

And they were acutely aware that they stood in opposition to the enslaving hedonism of the Persians.

The great Theban heroes Pelopidas and Epaminondas are also examples of moral heroism.

We know about them, primarily, through the writing of Plutarch, who lived in the first century AD -- that is, about 400 years after Aristotle and at least 900 years after Homer -- and whose work, which is best known in English as The Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans, is acutely concerned with the Aristotelian questions of complete areté and an ennobled self-love leading to acts of the highest magnanimity -- that is, acts of moral heroism.

In Plutarch's description of Pelopidas and Epaminondas, he notes that Pelopidas, who'd inherited a considerable estate, used it to better the situation of the poor in Thebes;

but amongst all his friends he could never persuade Epaminondas to be a sharer in his wealth. He, however, stepped down into his [Epaminondas'] poverty, and took pleasure in the same poor attire, spare diet, unwearied endurance of hardships, and unshrinking boldness in war; like Capaneus in Euripides, who had --

abundant wealth and in that wealth no pride

he was ashamed that any one should think that he spent more upon his person than the meanest Theban.

Epaminondas made his familiar and hereditary poverty more light and easy by his philosophy and single life; but Pelopidas married a woman of good family and had children ...

Both seemed equally fitted by nature for all sorts of excellence; but bodily exercises chiefly delighted Pelopidas, learning Epaminondas; and the one spent his spare hours in hunting and the Palaestra, the other in hearing lectures or philosophising. And, amongst a thousand points for praise in both, the judicious esteem nothing equal to that constant benevolence and friendship, which they inviolably preserved in all their expeditions, public actions, and administration of the commonwealth. For if any one looks on the administrations of Aristides and Themistocles, of Cimon and Pericles, of Nicias and Alcibiades, what envy, what mutual jealousy appears? And if he then casts his eye on the kindness and reverence that Pelopidas showed Epaminondas, he must needs confess that these are more truly and more justly styled colleagues in government and command than the others, who strove rather to overcome one another than their enemies.

The true cause of this was their virtue; whence it came that they did not make their actions aim at wealth and glory, an endeavour sure to lead to bitter and contentious jealousy; but both from the beginning being inflamed with a divine desire of seeing their country glorious by their exertions, they used to that end one another's excellences as their own. Many, indeed, think this strict and entire affection is to be dated from the battle at Mantinea, where they both fought, being part of the succours that were sent from Thebes to the Lacedaemonians, their then friends and allies. For, being placed together among the infantry, and engaging the Arcadians, when the Lacedaemonian wing, in which they fought, gave ground, and many fled, they closed their shields together and resisted the assailants.

Pelopidas, having received seven wounds in the forepart of his body, fell upon an heap of slain friends and enemies; but Epaminondas, though he thought him past recovery, advanced to defend his arms and body, and singly fought a multitude, resolving rather to die than forsake his helpless Pelopidas.

And now, he being much distressed, being wounded in the breast by a spear, and in the arm by a sword, Agesipolis, the King of the Spartans, came to his succour from the other wing, and beyond hope delivered both. ...

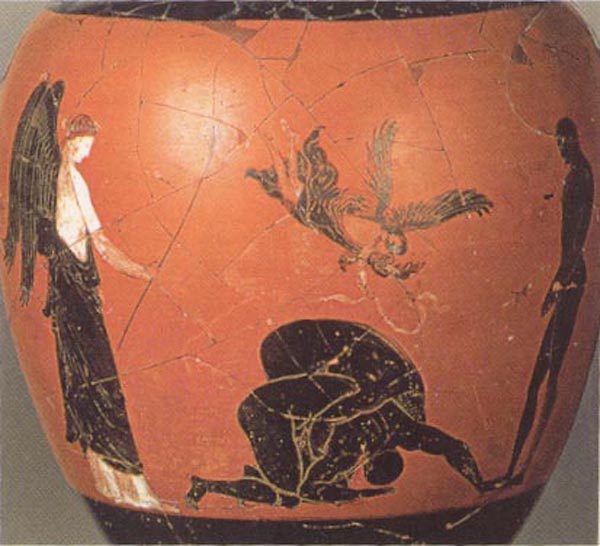

That act -- of defending a fallen comrade -- is an act of Homeric areté:

Defending a fallen comrade

Defending a fallen comrade -- a common scene in vase painting

But in the persons of Pelopidas and Epaminondas, it leads to an excellence which benefits the entire commonwealth or city-state of Thebes, and which also results in the freeing of the Spartan helots and the restoration of Messenia.

Acts of the highest moral heroism.

Acts which cost both of them their lives.

Plutarch:

The true cause of this was their virtue; whence it came that they did not make their actions aim at wealth and glory, an endeavour sure to lead to bitter and contentious jealousy; but both from the beginning being inflamed with a divine desire of seeing their country glorious by their exertions, they used to that end one another's excellences as their own.

Alexander the Great too expresses a striving for complete areté, an ennobled self-love, and acts of the highest moral heroism.

But that's not surprising, given that he was tutored by Aristotle.

Indeed, when you read Jaeger, you can see that Alexander -- though hardly alone in this respect among the Greeks -- spent his life putting into practice the Hellenic ideals of areté and honor:

Aristotle's own words are quite clear. They show that he was thinking chiefly of acts of moral heroism. A man who loves himself will (he thought) always be ready to sacrifice himself for his friends or his country, to abandon possessions and honours in order to 'take possession of the beautiful'. The strange phrase is repeated: and we can now see why Aristotle should think that the utmost sacrifice to an ideal is a proof of a highly developed self-love. 'For,' he says, 'such a man would prefer short intense pleasures to long quiet ones; would choose to live nobly for a year rather than to pass many years of ordinary life; would rather do one great and noble deed than many small ones.'

That's exactly how Alexander lived:

"always .. ready to sacrifice himself for his friends or his country, to abandon possessions and honours in order to 'take possession of the beautiful'."

Why?

Because "the utmost sacrifice to an ideal is proof of a highly developed self-love."

Aristotle: "For such a man would prefer short intense pleasures to long quiet ones; would choose to live nobly for a year rather than to pass many years of ordinary life; would rather do one great and noble deed than many small ones."

That is, as Mary Renault puts it, "trading glory for length of days."

That's Alexander the Great and it's areté.

It's also the late Roman and last "pagan" -- that is to say, Hellenist -- emperor Julian, who lived almost seven hundred years after Alexander, and who clearly modeled himself on Alexander -- and Achilles.

As a matter of fact we have a letter from Julian describing a visit he made, when still a student and still pretending to be a Christian, to the city which was on the site of Troy, a city called New Ilios --

whose obstensibly Christian bishop, Pegasius, was quietly maintaining the temples and shrines and even sacrificing to Achilles:

Hector has a hero's shrine there and his bronze statue stands in a tiny little temple. Opposite this they have set up a figure of the great Achilles in the unroofed court. ... Now I found that the altars were still alight, I might almost say still blazing, and that the statue of Hector had been anointed till it shone. So I looked at Pegasius and said, "What does this mean? Do the people of Ilios offer sacrifices?" This was to test him cautiously to find out his own views. He replied: "Is it not natural that they should worship a brave man who was their own citizen, just as we [Christians] worship the martyrs?" Now the analogy was far from sound; but his point of view and intentions were those of a man of culture, if you consider the times in which we then lived.

When Julian says "culture," of course, he means Hellenism.

And "the times" of course were a period of persecution, by the Christians, of Hellenists -- "pagans."

Julian's letter was written when he was emperor and had put a stop, all too brief, to those persecutions.

Julian adds:

Thereupon with the greatest eagerness he led me to [a shrine of Athene] and opened the temple, and as though he were producing evidence he showed me all the statues in perfect preservation, nor did he behave at all as these impious men [the Christians] do usually, I mean when they make the sign on their impious foreheads, nor did he hiss to himself as they do. For these two things are the quintessence of their theology, to hiss at demons and make the sign of the cross on their foreheads.

~ Letters of Julian, translated by W C Wright.

When Julian says Christians would "hiss at demons," the "demons" were the statues of the gods.

And of athletes too.

Hissing, along with making clicking noises with the tongue, was thought to ward off evil.

Enlightened bunch, huh?

But why hiss at a statue -- when you could just obliterate it?

That's why, over time, and except for those which had been buried, the statues were either vandalized and desecrated genitally,

or completely destroyed.

And it's why we have so few original Greek statues.

Nevertheless, what's important to understand is that in Julian's time -- his visit to New Ilios was in 354 AD -- Achilles was still revered and treated as a god.

And Achilles, along with Alexander, was clearly a role model and hero for Julian.

So: this Homeric idea and Hellenic ideal of areté runs through the centuries of Hellenism.

And I want you to see that for a thousand years, Men, molded, as Jaeger says, by a great educational system, modeled their lives on those of Heroes.

That's not pie in the sky -- that's how it actually was.

Because Greek ethical thought provides a model or paradigm of *moral heroism* -- beginning with Achilles.

Here again is Jaeger