A Warrior's Prayer

2-3-11

In Worshipping the Warrior God we spoke of how the Warrior needs the Warrior God in his life.

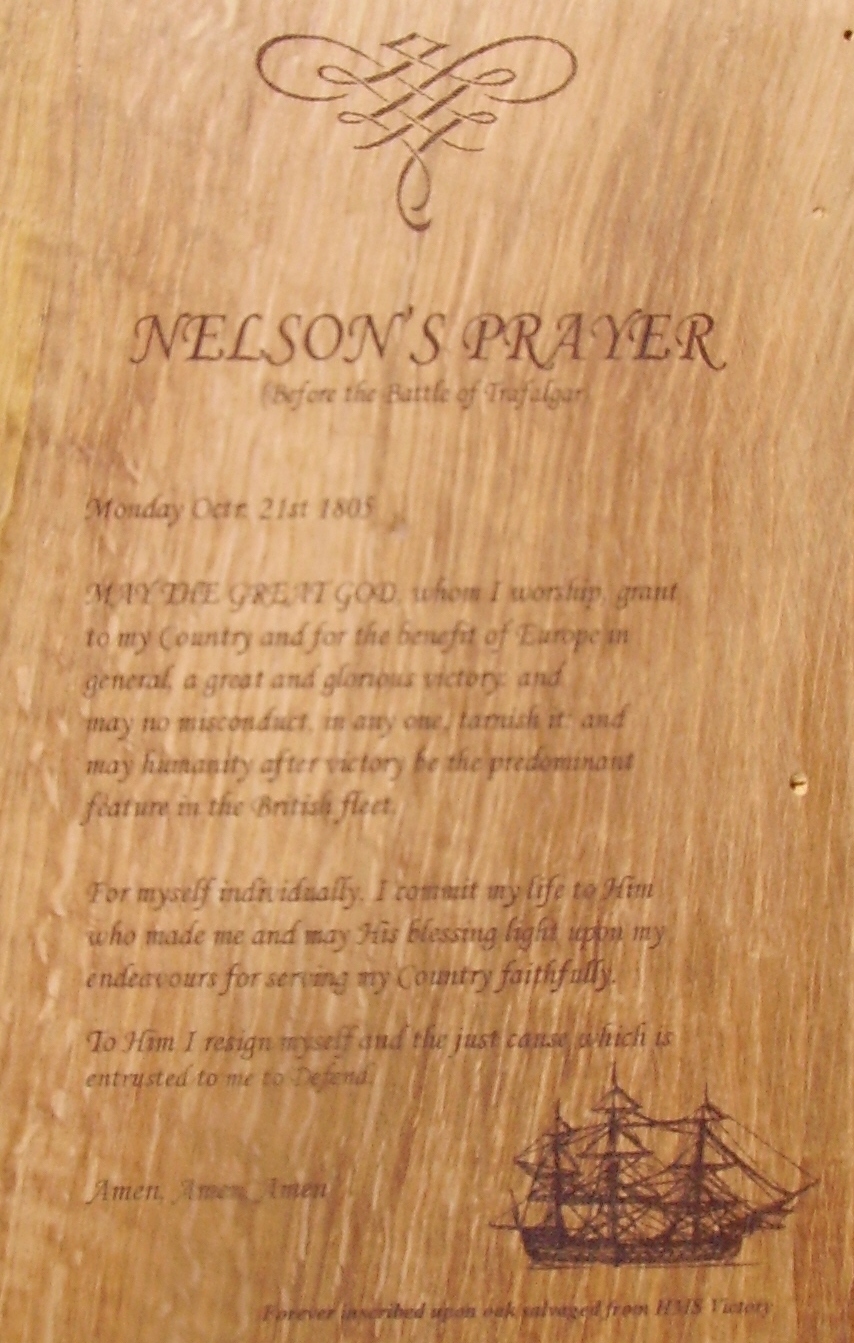

Well, even a famous Warrior needs to pray before battle and for example: On board HMS Victory, 21st October 1805, Vice Admiral Horatio, Lord Nelson, KB wrote this prayer.

For myself individually, I commit my life to Him

To Him I resign myself and the just cause which is

AMEN, AMEN, AMEN

This goes to show that even a great commander such as Nelson can depend on the Warrior God, and so if it is good enough for him then it is good enough for any Warrior to commit his all to Him.

Yes, the Battle of Trafalgar was the victory that Nelson prayed for, but as most folks know Nelson was badly wounded by a musket shot from a French sniper, and he was taken below decks into the cockpit were he died; and Yes, I do think that he was in the arms of Captain Thomas Hardy, who yes I also believe did give Nelson a last kiss, after all they were both masculine men, and (if the comments are accurately reported) when Hardy said about giving the kiss "But what will they say at the Admiralty?" Nelson replied "They can only be jealous, (of our love) Hardy" so Hardy went ahead and kissed his commander. Two men, bound together in war and in love.

MAY THE GREAT GOD, whom I worship, grant,

to my Country, and for the benefit of Europe in

general, a great and glorious Victory; and

may no misconduct, in any one, tarnish it; and

may humanity after victory be the predominant

feature in the British Fleet.

who made me and may His blessing light upon my

endeavours for serving my Country faithfully.

entrusted to me to defend.

Nelson

Hardy

With Warrior Love

Brian

Also by Warrior Brian Hulme:

The credit crunch will NOT crunch my Manhood my Masculinity or my Warriorhood

CAN MY MAN TO MAN RELATIONSHIP DRAW ME CLOSER TO GOD?

14th February -- or -- EROS DAY?

The Warrior Altruism of the Warrior God

The Life and Times of Willy the Dick

Reply from:

Re: A Warrior's Prayer

2-5-2011

Thank you Warrior Brian Hulme.

Another excellent post!

Guys, Admiral Nelson's "bisexuality" was apparently well-known to his friends.

Nelson was essentially an 18th-century Man, and his sort of male-male / male-female sexuality was not unusual.

So -- it does appear that as he lay dying, he said to Hardy, "Kiss me, Hardy" -- and Hardy did.

Afterwards, as Victorianism took hold, some biographers claimed that Nelson had said, "Kismet, Hardy" -- "kismet" being a Persian word meaning "Fate."

But that word was not known to English-speakers in 1805.

Nelson said -- Kiss me, Hardy.

That's what he said.

And that's what Hardy did.

Now, what's interesting is the way Nelson's life has echoes in that of another great admiral, Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan.

Just as Nelson had been an 18th-century Man, so was Mahan a 19th-century Man, and their deaths, Nelson's in 1805, Thayer's in 1914, serve in some ways as bookends to the nineteenth century, which many feel didn't end until 1914, and the outbreak of WW I.

But that's not all.

Because both Admirals were "bisexual," and both had male-female marriages and male-male lovers.

Which was not unusual.

For in the 19th century, as in the 18th, it was common for Men to form passionate relationships, usually starting early in life, with other Men.

For example, in his book, Picturing Men: A Century of Male Relationships in Everyday American Photography, which is on the Heroes Reading List, and which we discuss in Warriorhood and Male Intimacy, Cal State Fullerton Prof John Ibson talks about Admiral Mahan, well-known as the "father of the modern American navy" and as the author of a tremendously important book, The Influence of Sea Power upon History, which in turn had a huge influence on President Theodore Roosevelt's foreign policy.

Think Panama Canal guys.

What is less well known, says Ibson, is

the extensive and highly romantic correspondence that Admiral Mahan carried on with a fellow officer, Samuel Ashe, letters documenting a relationship of forty years that had begun when both were Annapolis midshipmen before the Civil War.In one letter, Mahan provocatively wrote: "I lay in bed last night, dear Sam, thinking of the gradual rise and growth of our friendship. My first visit ever to your room is vividly before me, and how as I went up there night after night I could feel my attachment to you growing and see your own love for me showing itself more and more every night."

"When you come to a question of sex," wrote the father of the navy on another occasion, "on the whole commend me to men."

No kidding.

And Ibson says

Before homosexuality was culturally conceived as a condition rather than simply an activity, there was perhaps less anxiety in the military, as in society at large, about the precise line between acceptable and forbidden degrees of closeness between men. Photographs of American military men from the Civil War through World War I document, as they must also have nurtured, an environment of even more intimacy than one sees in civilian photos of the same era.

And notice that Ibson makes a key differentiation between sex "as a condition rather than an activity."

Those of you who don't understand what that difference is about should read our Man2Man Alliance Policy Paper, Sex Between Men: An Activity, Not A Condition.

Again, it's very important, if you don't understand the difference, to read Sex Between Men: An Activity, Not A Condition.

So both Nelson, the great British admiral of the 18th century and the Napoleonic Wars -- and Mahan -- the great American admiral of the 19th century and the Spanish-American War -- were involved in romantic and passionate male-male love affairs.

Again, such was not unusual in the 18th and 19th century, either in Europe or America.

And in America, as abroad, there were numerous writers who referred in their work, either implicitly or explicitly, to Man2Man.

Among them were Melville -- Typee, Omoo, Redburn, Billy Budd, Moby Dick; and Walt Whitman.

In Europe, as in America, male-male was not restricted to the Navy.

Prior to WW I, the German officer corps was notorious for male-male.

D.H. Lawrence wrote a famous and much anthologized, even today, short story about male-male titled "The Prussian Officer";

while Kaiser Wilhelm II had a circle of friends into male-male.

So male-male, particularly among Men who were also into male-female, was not unusual in the 19th and even early 20th century centuries.

But that fact isn't easily accepted by people today, bound as they are by heterosexualization and the false categories of sexual orientation.

I had good cause to think about that after Warrior Jim S sent me a link to a book review of the life of Jack London.

The review appeared in May of 2010, and what was interesting in it was how the author of the biography, a Mr Haley, appeared to anachronistically attribute to Mr London a sort of "homosexuality" which would obviously have been foreign to him;

while at the same time the reviewer, travel writer Alexander Theroux, objected strenuously to any suggestion that London could have been "homosexual."

In point of fact, what's apparent from the review is that London, who was born in the nineteenth and died in the twentieth centuries (1876 - 1916) -- is that London himself had no interest in the concept of "homosexuality," simply believing that male-male was a necessary part of any Man's life.

Here's the review -- and because I suspect many people today aren't familiar with London, I'm pasting in the review in its entirety.

Wolf: The Lives of Jack London

By James L. Haley

Basic Books, 364 pages, $29.95

The author known for 'The Call of the Wild' was a man of protean passions

[Book reviewed] By ALEXANDER THEROUX

Jack London, born John Griffith Chaney in 1876, grew up a working-class, fatherless boy in Oakland, Calif., and spent his teen years riding the rails, thieving oysters, sailing on a seal-hunting schooner and toiling as what he would later call a "work beast," shoveling coal, working in a cannery, loading bobbins in a jute mill, ironing shirts in a steam laundry. Somehow he also found time to spend in libraries and became an enthusiastic reader of novels and travel books at an early age.

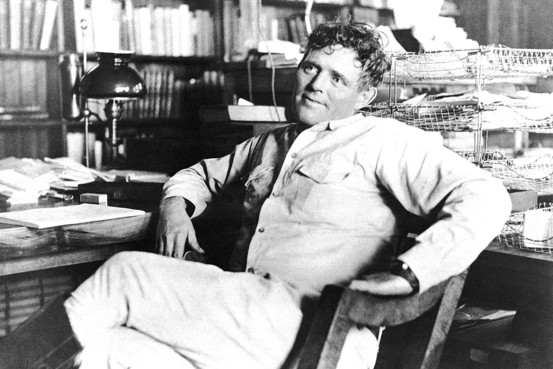

Jack London at his desk in 1916, the year he died at age 40.On the sealing schooner in 1873 he had survived a harrowing run-in with a typhoon. The stories he told about the storm after his return home prompted his mother, when she saw the announcement of a writing contest in the San Francisco Morning Call asking for descriptive articles by local writers 22 years old or younger, to urge her son to write up his typhoon experience for the contest. The 17-year-old London won the $25 first prize, "beating out students from Stanford and Berkeley with his eighth-grade education," writes biographer James L. Haley in "Wolf: The Lives of Jack London." The prize money, Mr. Haley notes, was the equivalent of a month's wages in the London household. "Jack London, author, was born."

The young man plunged into writing short stories -- but found that he couldn't sell them. He made a trip to the East Coast in 1874 (spending a month unjustly jailed as a vagrant in Buffalo), returned to Oakland and enrolled at the University of California at Berkeley, only to withdraw after a semester. Hearing news of a gold strike in the Canadian Yukon Territory, he was hit by a case of "Klondicitis" and headed north. He came back flat broke at 22, more determined than ever to make a living as a writer. London's first-hand experience of life in America's penniless subculture turned him into a committed socialist for the rest of his life -- which was not all that long. He died at age 40; during the intervening two decades he would become the highest-paid writer in the country.

The book that made him a national celebrity, at age 27, was "The Call of the Wild," a novel about a domesticated dog that eventually finds its true self in the raw life of a sled dog in the Yukon. Suddenly it seemed that London knew everybody in the writing world. Sinclair Lewis, Ambrose Bierce, Emma Goldman, Upton Sinclair, Lincoln Steffens, Ida Tarbell and many others counted the young, red-blooded author as their friend.

Mr. Haley says that he does not intend, with "Wolf," to recapitulate what has already been written about London, whether in adulatory biographies or lit-crit monographs. The author wants to explore the forgotten, the "real" Jack London, concluding that "what London needs is a biographer's eye -- not the eye of a vestal flametender, nor an acolyte, nor a revisionist, but a biographer's eye, from totally outside the existing circle." Thus we are treated to portraits of London's father, William Chaney, an itinerant evangelizing astrologer; of his shrewish mother, Flora Wellman, a woman who was born into wealth in Ohio and fled both; and of John London, a Civil War veteran from Pennsylvania who married Flora when London was eight months old, giving her a "chance at respectability."

We also meet London's demanding, unforgiving first wife, Bessie, and their two daughters; his African- American wet nurse, a splendid force in his life, named Virginia Prentiss; and, notably, the lusty and lovely but often traduced Charmian Kittredge, the offspring of parents who had dabbled in free love, whom London married on a lecture tour in Chicago in 1906.

Prolific, irrepressible, madly energetic, London wrote a thousand words a day without fail, compulsively, whether or not he was inspired. At his peak he often wrote as many as two books a year. In 1913 alone he published the story collection "The Night Born," two novels ("The Abysmal Brute" and "The Valley of the Moon"), along with his famous "alcoholic memoir" "John Barleycorn," in which he confessed to a lifelong struggle with booze. Temperance advocates used "John Barleycorn" in their push for prohibition; liquor companies denounced it; a popular movie was made of it; ministers cited it in sermons.

London lived hard and intensely, and the plural "lives" to which Mr. Haley refers in the book's subtitle sound plausible. London was a reporter as well as a novelist -- Hearst paid him to cover the Russo-Japanese War in 1904 -- and traveled to the far ends of the planet. He was an omnivorous reader. On cross-country jaunts he lectured about the evils of capitalism. He ate indiscriminately (raw pressed duck was a favorite) and smoked cigarettes until the end of his life. A free spirit, he loved bicycling, flying kites and listening to music -- Charmian was a virtuoso pianist. Having traveled to Hawaii and surfed "until the tropical sun almost killed him," London "introduced the sport to the world" in 1911 with "The Cruise of the Snark," an account of a Pacific sailing expedition.

Although London was famous for depicting the brutality of nature in his work, he also celebrated animals in novels such as "The Sea-Wolf" and "White Fang" and was tender-hearted toward them in life. London owned a California ranch, where he kept horses, dogs and pigs. Upon seeing a bullfight in Quito, Ecuador, in 1909, he found it so revolting that he excoriated the sport in his story "The Madness of John Harned." London wept at the deaths of his pets.

The common picture of London presents a robustly physical man with, sadly for Charmian, an almost athletic enthusiasm for philandering. But Mr. Haley wants to give us the "real" Jack London, and so -- perhaps inevitably, given the times we live in and the nature of contemporary literary biography -- we are treated to endless speculation about London's possible homosexuality. In a July 1903 letter to Charmian, written on the cusp of their marriage and obviously seeking her sympathy, London laments that he has "never had a comrade" and yearns for a "great Man-Comrade" who should be "so much one with me that we could never misunderstand," adding: "He should love the flesh, as he should the spirit."

Mr. Haley makes much of this. He also focuses attention on London's friendship with the poet George Sterling. London called him the "Greek" on account of his classical good looks; Sterling called him Wolf. The two were indeed close. Sterling's editorial gifts influenced "The Call of the Wild," and Charmian, before the marriage, fretted about how much time London spent with his friend.

It wouldn't have been the first time that a fiance resented her intended's pals, but Mr. Haley sees something more. "Sterling alone held the potential to embrace a soul as vast and complex as his own," he writes. "London was never bashful about recommending the therapeutic value of recreational sex, and Sterling was equally forthright in his contention that orgasms liberated creativity. Although the most noted affairs of both men were certainly with women, it seems not improbable that Wolf and the Greek found time and circumstance for one another, but neither man ever committed to paper how deep their relationship extended." Readers can be pardoned for thinking it seems not improbable that London, given the chance, would punch Mr. Haley in the nose.

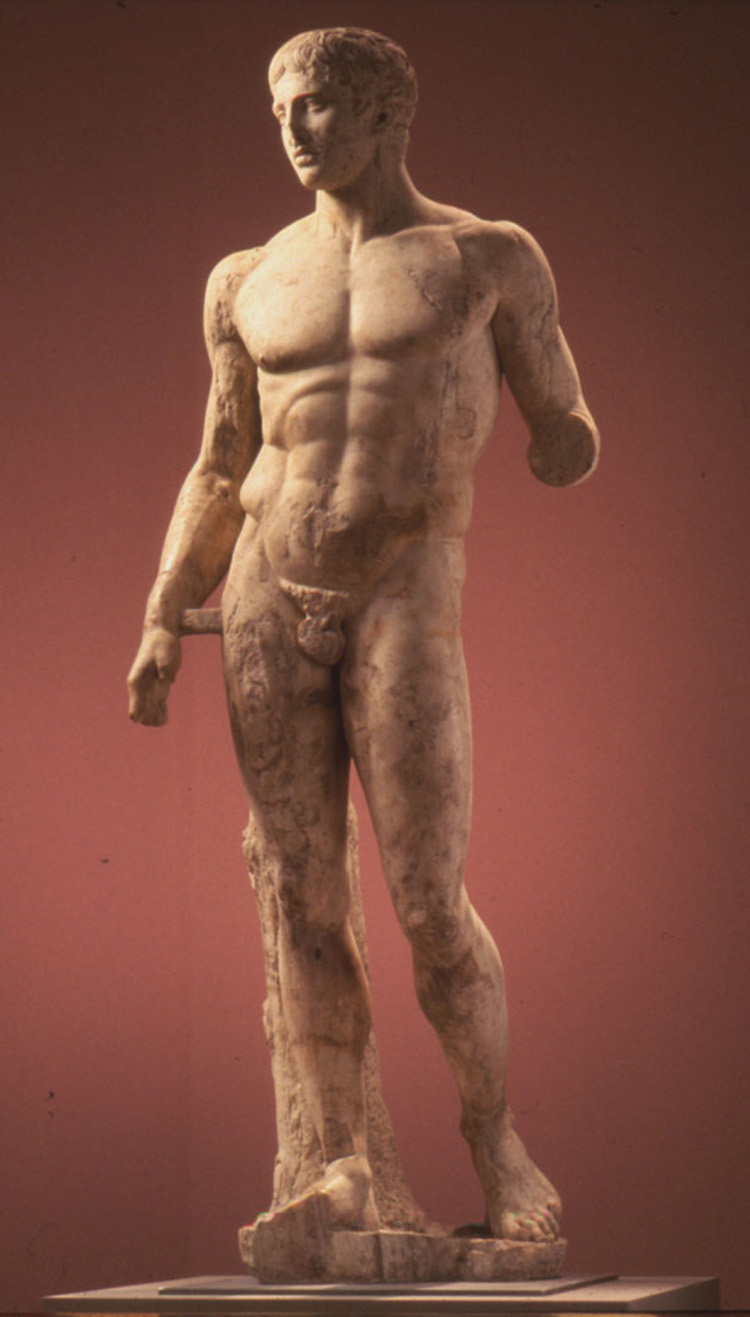

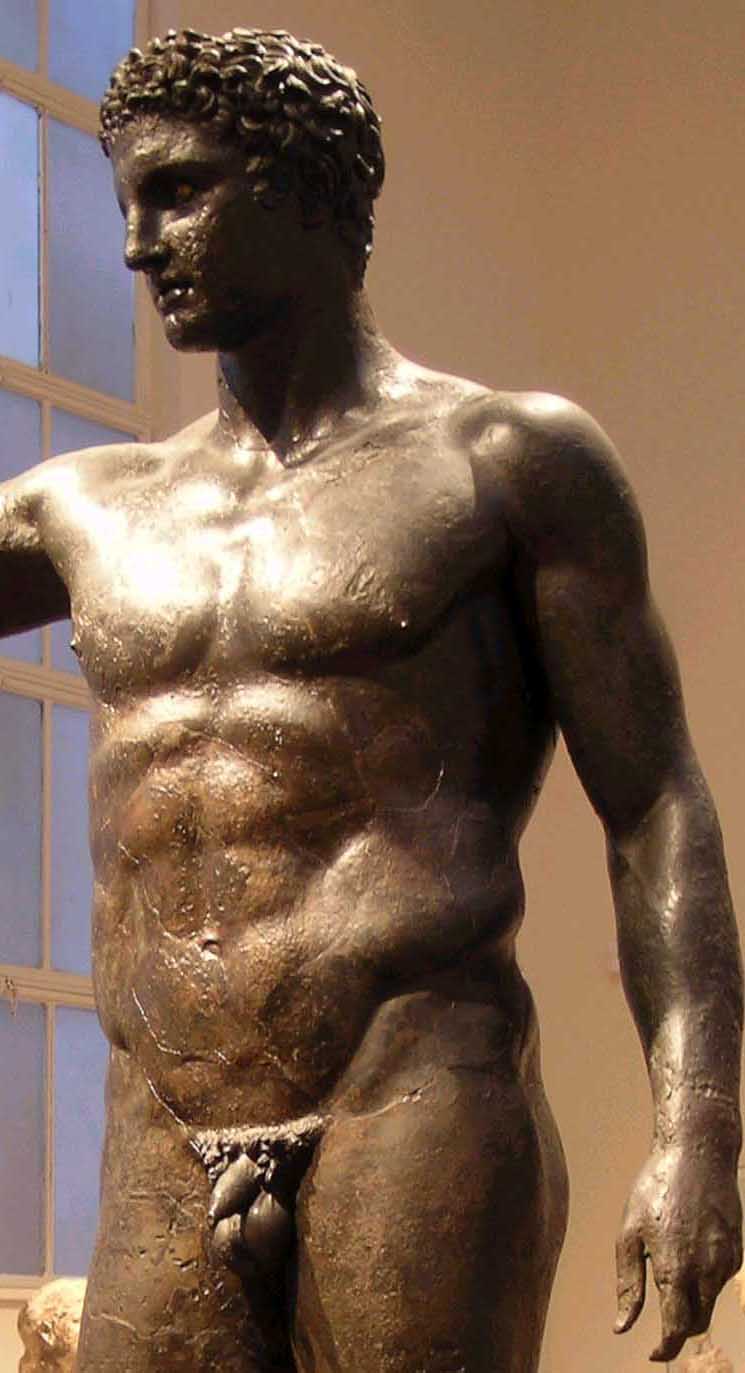

Mr. Haley is almost prurient with his gaydar. He speculates on the nature of male comradeship during the 17-year-old London's sealing trip to Japan. The author finds homosexual undertones in the brutal naturalism of "The Sea-Wolf." In London's boxing novel, "The Game," Mr. Haley finds "surprisingly" lyrical descriptions of male beauty, stripped and muscular, and he raises an eyebrow over photographs of London "minimally-clad" in "he-man poses." London "was proud of his blond-beastly body," we're told, "and was not shy about showing it off. Unpublished nudes of him also exist."

Mr. Haley concedes -- it feels grudging -- that he has no solid evidence for London's homosexuality, yet he insists on keeping the theme alive throughout the book. That misguided decision mars "Wolf" (as does, in a minor way, the author's maddening misuse of the word "disinterest"). But this is still a valuable London biography. It surpasses Irving Stone's 1938 "Sailor on Horseback," giving us a well-delineated picture of a singular, complicated figure, a socialist who signed his letters "Yours for the revolution, Jack London" but who traveled for decades -- often first-class -- with an Asian servant who was required to call him "Master." London was an anti-capitalist who wildly speculated in schemes like importing and selling Australian eucalyptus trees in hopes that he would make a killing as they replaced Eastern hardwoods -- in one season he planted 16,000 of them. He was a polemicist who pleaded for the waifs in London but built a four-story castle on the extravagant 1,000-acre Beauty Ranch near Glen Ellen, Calif. "His socialism was not about banning wealth," Mr. Haley notes. "It was about banning wealth accrued by exploiting others."

These days we have little sense of the literary glory that Jack London. When he is read at all, it is predominantly as a writer of boy's books. The daring novel he wrote in 1907, "Before Adam," is a fiercely imaginative, Darwinian tale about a caged lion in a circus, and it is fascinating in its exploration of atavistic memory. The book sold 65,000 copies a century ago but is virtually unknown today. Thanks to James Haley's zeal, the author of that novel, not just the man of "The Call of the Wild" fame, is before us again.

Mr. Theroux's latest novel is "Laura Warholic: Or, The Sexual Intellectual" (Fantagraphics).

So -- what's interesting in the review is the conflict between Mr Theroux and Mr Haley.

Both of whom, from my point of view -- and our point of view in the Alliance -- are wrong.

Mr Theroux, the reviewer, is, in effect, accusing Mr Haley, the book's author, of "over-homosexualizing" Jack London -- while Mr Theroux wants to deny that London would have had any male-male feelings --

despite the fact, as we've just seen, that male-male was not unusual in the 19th century, and particularly not among sailors -- which Jack London had been.

So let's take a closer look.

Here are the paragraphs from Mr Theroux's review which are critical of Haley's speculation about London and male-male:

The common picture of London presents a robustly physical man with, sadly for Charmian, an almost athletic enthusiasm for philandering. But Mr. Haley wants to give us the "real" Jack London, and so -- perhaps inevitably, given the times we live in and the nature of contemporary literary biography -- we are treated to endless speculation about London's possible homosexuality. In a July 1903 letter to Charmian, written on the cusp of their marriage and obviously seeking her sympathy, London laments that he has "never had a comrade" and yearns for a "great Man-Comrade" who should be "so much one with me that we could never misunderstand," adding: "He should love the flesh, as he should the spirit."

Mr. Haley makes much of this. He also focuses attention on London's friendship with the poet George Sterling. London called him the "Greek" on account of his classical good looks; Sterling called him Wolf. The two were indeed close. Sterling's editorial gifts influenced "The Call of the Wild," and Charmian, before the marriage, fretted about how much time London spent with his friend.

It wouldn't have been the first time that a fiance resented her intended's pals, but Mr. Haley sees something more. "Sterling alone held the potential to embrace a soul as vast and complex as his own," he writes. "London was never bashful about recommending the therapeutic value of recreational sex, and Sterling was equally forthright in his contention that orgasms liberated creativity. Although the most noted affairs of both men were certainly with women, it seems not improbable that Wolf and the Greek found time and circumstance for one another, but neither man ever committed to paper how deep their relationship extended." Readers can be pardoned for thinking it seems not improbable that London, given the chance, would punch Mr. Haley in the nose.

Mr. Haley is almost prurient with his gaydar. He speculates on the nature of male comradeship during the 17-year-old London's sealing trip to Japan. The author finds homosexual undertones in the brutal naturalism of "The Sea-Wolf." In London's boxing novel, "The Game," Mr. Haley finds "surprisingly" lyrical descriptions of male beauty, stripped and muscular, and he raises an eyebrow over photographs of London "minimally-clad" in "he-man poses." London "was proud of his blond-beastly body," we're told, "and was not shy about showing it off. Unpublished nudes of him also exist."

Mr. Haley concedes -- it feels grudging -- that he has no solid evidence for London's homosexuality, yet he insists on keeping the theme alive throughout the book. That misguided decision mars "Wolf" (as does, in a minor way, the author's maddening misuse of the word "disinterest"). But this is still a valuable London biography.

So -- the reviewer accuses the author, Mr Haley, of "endless speculation about London's possible homosexuality [sic]."

But Mr Haley has a rather striking -- and unequivocal -- statement from London to back up that speculation:

In a July 1903 letter to [his fiance] Charmian, written on the cusp of their marriage and obviously seeking her sympathy, London laments that he has "never had a comrade" and yearns for a "great Man-Comrade" who should be "so much one with me that we could never misunderstand," adding: "He should love the flesh, as he should the spirit."

Like I say, London's statement is unequivocal -- he says that he yearns for a "great Man-Comrade" -- a beautiful turn of phrase -- who would be always with him, "so much one with me that we could never misunderstand," adding: "He should love the flesh, as he should the spirit."

So -- London yearns for a great Man-Comrade who would be so much ONE with him that he could never misunderstand, and who would "love the flesh, as he should the spirit."

Like I say, that's unequivocal.

And it's something else too: that is, NOT unusual among nineteenth century Men -- as we just saw with Alfred Mahan and Samuel Ashe, who were great Man-Comrades, never, one hopes, misunderstood each other, and who loved the flesh as well as the spirit.

Remember what Mahan said: "When it comes to sex, commend me to Men."

Mahan wasn't equivocal, and neither was London.

Nevertheless, Mr Theroux objects.

"Mr Haley makes much of this [statment by London]," he says.

Well, in a sense he does, as I'll get into.

But Mr Haley is completely correct to bring this to the reader's attention.

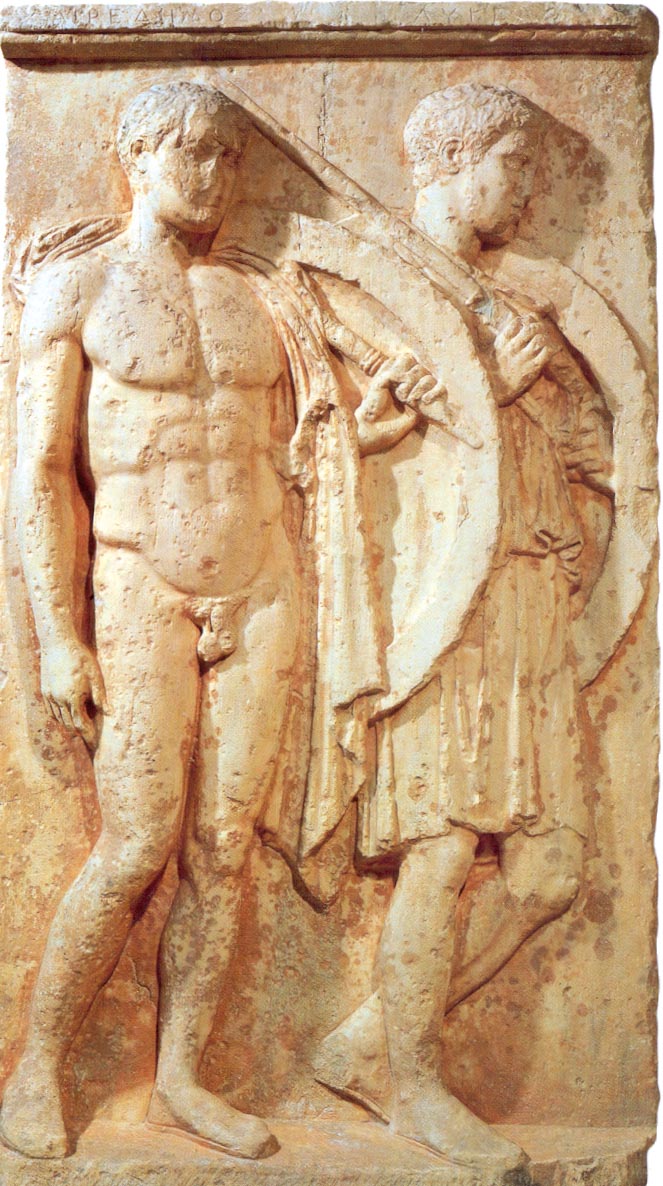

Mr Theroux doesn't agree, even though London had an intense male-male friendship with the poet George Sterling, whom he called the "Greek" -- "on account of his classical good looks," says Theroux, but to us an obvious reference to the ancient Greek tradition of male-male, Man2Man, and Manly and Martial Love between two great and Heroic Man-Comrades:

"Sterling alone held the potential to embrace a soul as vast and complex as his own," [Haley] writes. "London was never bashful about recommending the therapeutic value of recreational sex, and Sterling was equally forthright in his contention that orgasms liberated creativity. Although the most noted affairs of both men were certainly with women, it seems not improbable that Wolf and the Greek found time and circumstance for one another, but neither man ever committed to paper how deep their relationship extended." Readers can be pardoned for thinking it seems not improbable that London, given the chance, would punch Mr. Haley in the nose.

Is that right?

Would London have punched Mr Haley in the nose for implying that he and Mr Sterling might have loved each other physically?

NO.

Not given, first of all, what London himself had said about his need for a "great Man-Comrade" who would "love the flesh, as he should the spirit."

Now it's true that London lived in an era of accelerating heterosexualization, and it's possible that he would have, in certain circumstances, felt pressure to deny any interest in male-male.

But given London's free-wheeling and, more to the point, free-speaking spirit, that doesn't seem likely to me.

He was a "womanizer" -- he had many affairs with Women.

I have no doubt that, given when he lived, and given that he was an artist, a "bohemian," that he could easily have gotten away with talk of and action with a Man-Comrade, etc.

Indeed, given London's character, it seems more likely to me that Jack London, were he alive today, would punch Mr Theroux in the nose for trying to make him deny his LOVE for George Sterling and thereby shame that Love -- the Love he shared with his great Man-Comrade.

Mr Theroux nevertheless continues:

Mr. Haley is almost prurient with his gaydar. He speculates on the nature of male comradeship during the 17-year-old London's sealing trip to Japan. The author finds homosexual undertones in the brutal naturalism of "The Sea-Wolf." In London's boxing novel, "The Game," Mr. Haley finds "surprisingly" lyrical descriptions of male beauty, stripped and muscular, and he raises an eyebrow over photographs of London "minimally-clad" in "he-man poses." London "was proud of his blond-beastly body," we're told, "and was not shy about showing it off. Unpublished nudes of him also exist."

So -- Mr Theroux accuses Mr Haley of being "almost prurient with his gaydar [sic]."

Is he?

I don't know, because I haven't read the book, and I certainly hope that Mr Haley doesn't use the anachronistic and very silly word "gaydar" to describe what is simply the male's normal and natural recognition of his mutually affectionate and sexual interest in other Men.

As my foreign friend says:

Male sexual interest in other Men cannot be tied to a minority group.It is a Universal Male Phenomenon, especially strong among Masculine Men.

And Jack London was certainly a Masculine Man.

For just those reasons, Mr Haley is clearly not wrong to speculate "on the nature of male comradeship during the 17-year-old London's sealing trip to Japan" -- especially given the many contemporary accounts we have of same-sex among sailors in the nineteenth -- and twentieth -- centuries.

Nor is Mr Haley wrong to find "homosexual [sic] undertones in the brutal naturalism of "The Sea-Wolf." "

Anymore than Melville was wrong to find same-sex "undertones" aboard the Pequod.

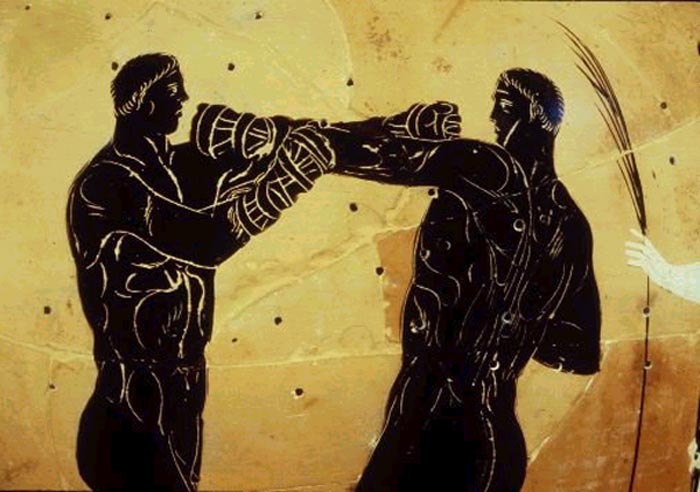

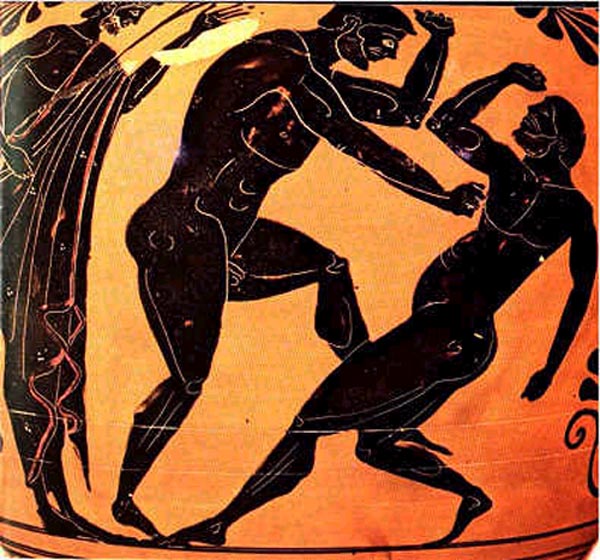

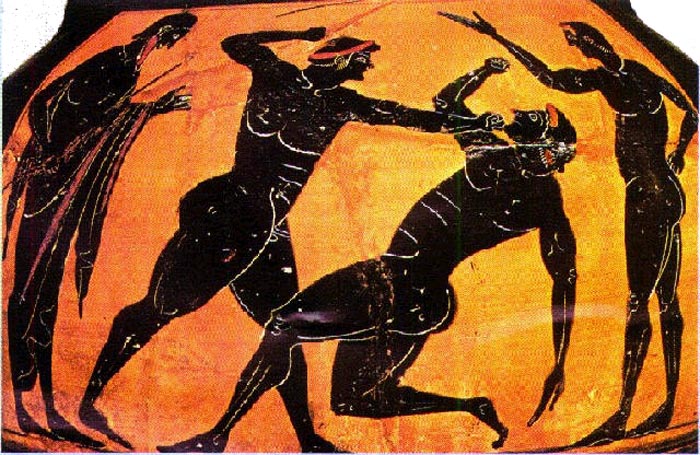

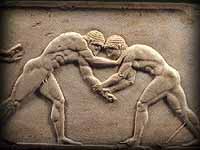

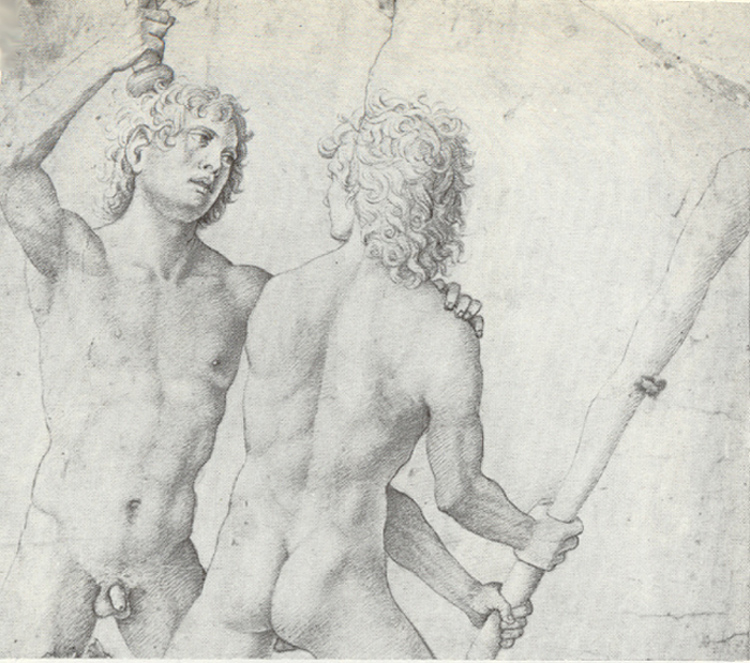

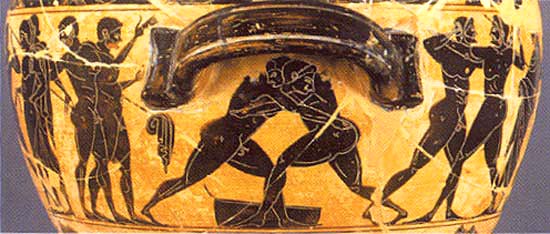

Mr Theroux complains that "In London's boxing novel, "The Game," Mr. Haley finds "surprisingly" lyrical descriptions of male beauty, stripped and muscular" -- but why shouldn't one male lyrically describe the Manly and Brave Beauty of other males, Boxers and other Fighters, "stripped and muscular?"

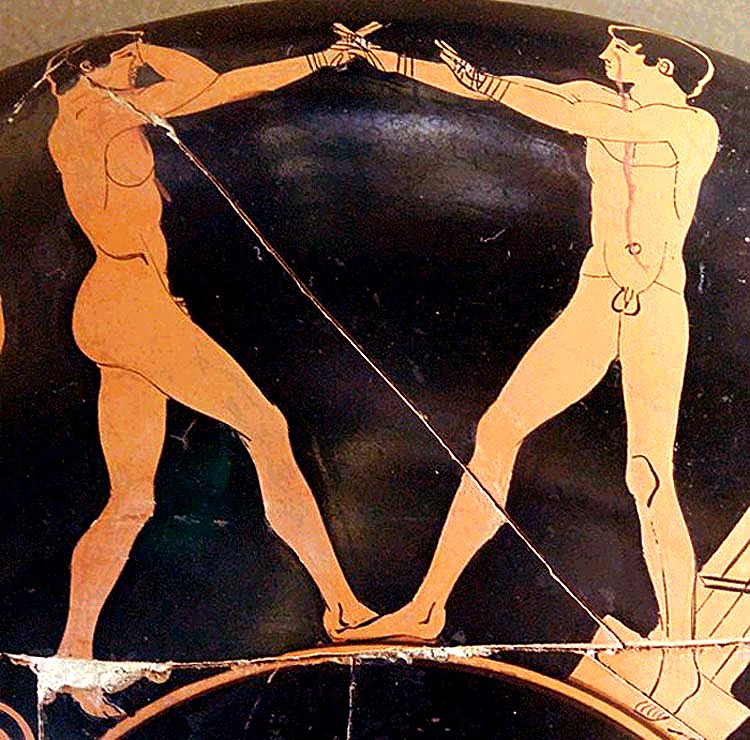

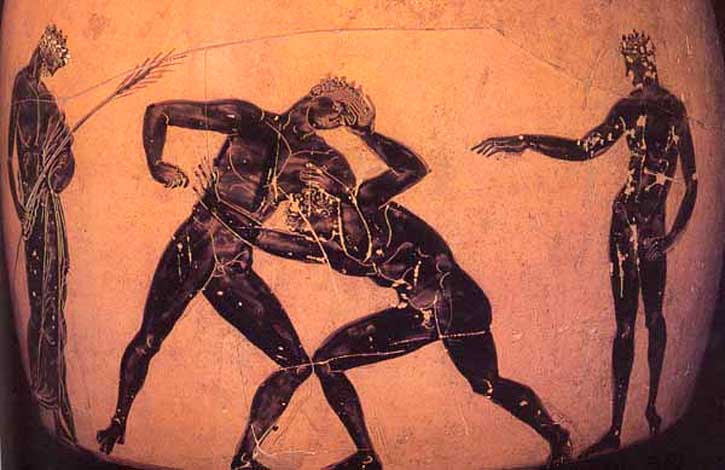

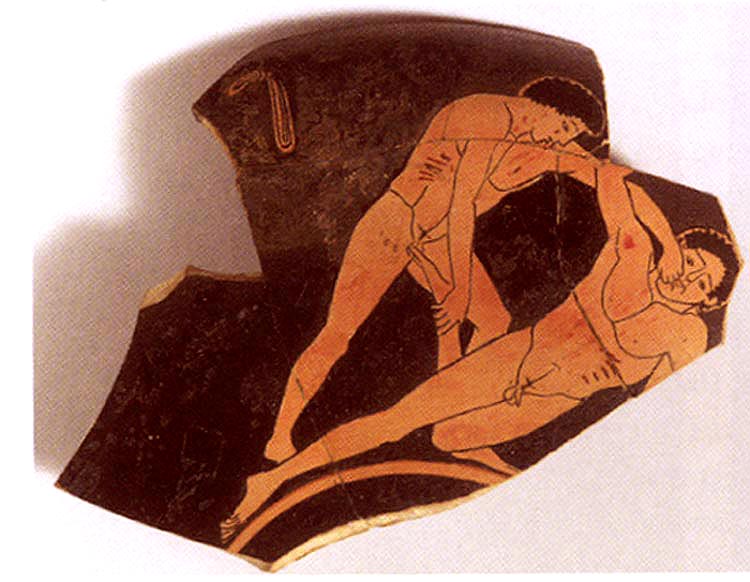

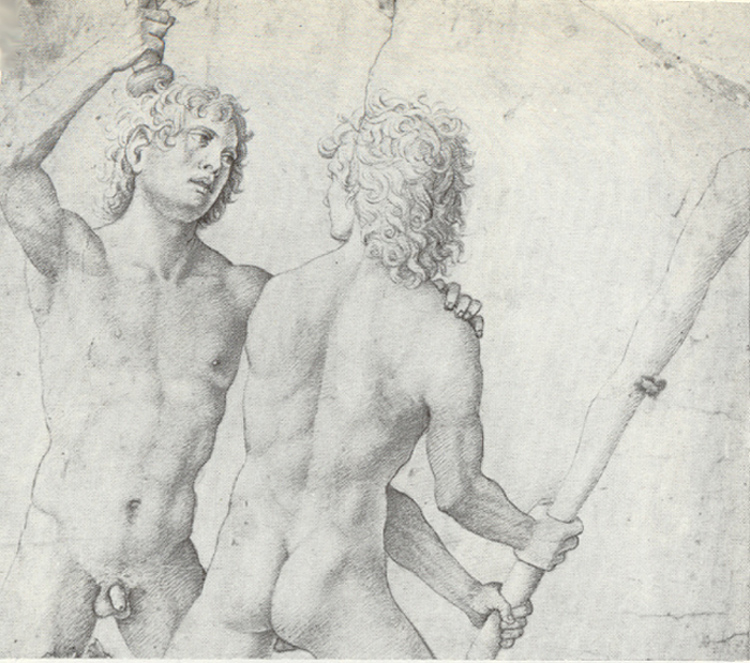

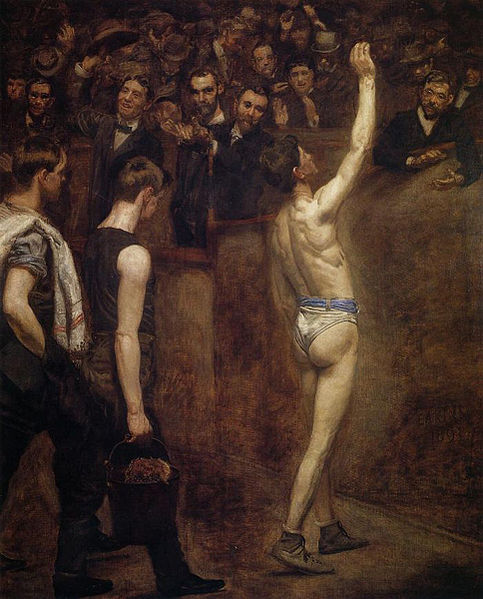

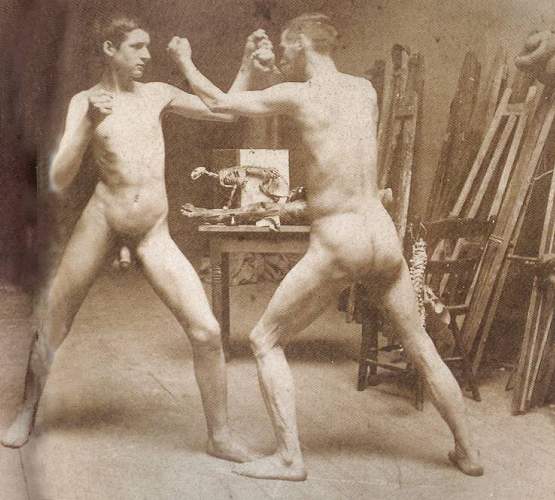

In point of fact, paintings and photographs depicting the Brave Beauty of Boxers were common in that era -- here, for example, is Eakins' famous 1898 "Salutat":

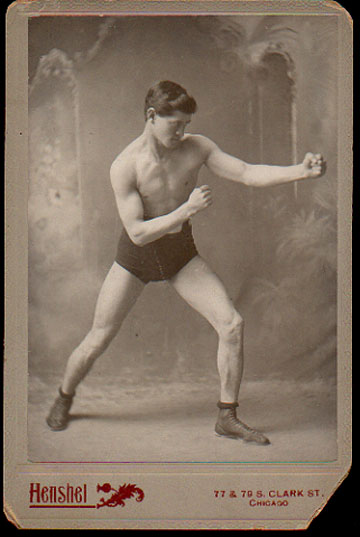

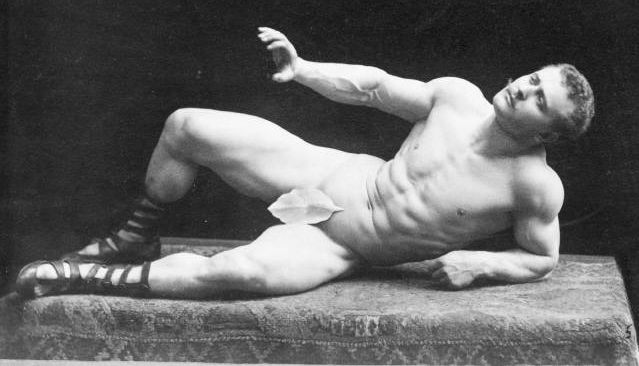

And here's a pic of the real-life boxer, Billy Smith, "stripped and muscular," who posed for the painting:

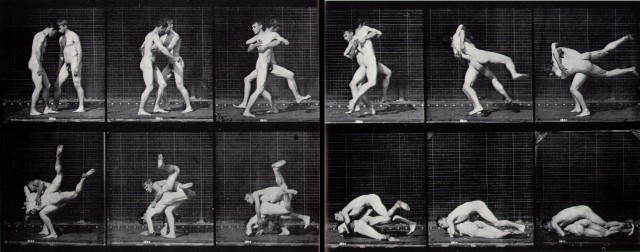

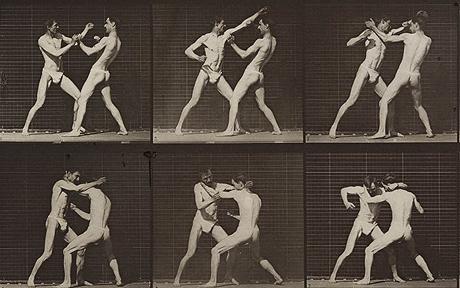

These paintings and photos, by the way, had been preceded by the work of Muybridge:

Again, such "lyricism" about the nude or almost-nude male body was not unusual in London's era.

This is the famous 1909 painting "Stag at Sharkey's":

Mr Theroux is also annoyed that the author "raises an eyebrow over photographs of London "minimally-clad" in "he-man poses." London "was proud of his blond-beastly body," we're told, "and was not shy about showing it off."

But again, as Warrior NW talks about in Awakened to Manliness, male posing of that sort -- "he-man poses" -- is done -- primarily -- for other males.

Males pose -- they flex -- in front of and FOR each other:

It's a normal male behavior, and it's directed at OTHER MALES.

Nor is it limited to UFC weigh-ins.

Males will pose for other males just about anywhere, including in their cars.

And such posing, like stripped and muscular boxing, was very much part of the culture of London's era.

Here, for example, is the famous Sandow:

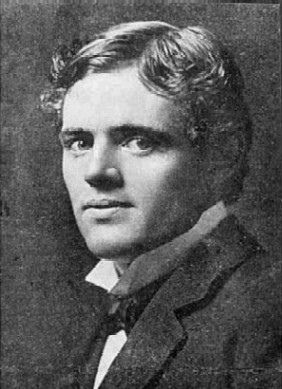

London was handsome of face:

and although the one pic I've seen of London in a "he-man pose" isn't particularly impressive by today's standards -- it was, no doubt, when married to his mind, more than enough for George Sterling.

So -- Mr Haley, the biography's author, is correct to see in these matters, pointers towards male-male.

But NOT "homosexual."

Although the word and concept of "homosexual" did exist during London's lifetime, we have to remember that he wasn't particulary well-educated -- much to his benefit -- and was without question what was called in those days a "freethinker."

At that point, the terms "homosexuality" and "homosexual" were used mainly by medical people and were applied to "neurotics" and "sexual inverts" -- effeminate, anally-receptive males.

London would simply not have seen himself -- nor been seen by others -- that way.

So -- to the extent that Mr Haley treats London as being some sort of proto-typical "gay man" -- he's wrong to do so;

but to be fair to Mr Haley, Mr Theroux never says he does that.

He just complains because Mr Haley has dared to suggest that London followed through on his desire, expressed, significantly, to his future-wife Charmian, for a "great Man-Comrade," who "should love the flesh, as he should the spirit."

And because Mr Haley suggests that in George Sterling, the "Greek," Mr London found his great Man-Comrade.

So -- it's clear to me that Mr Haley -- perhaps -- and Mr Theroux, certainly -- have anachronistic ideas about what they call "homosexuality."

For someone of Jack London's time and temperament, and as we've seen with both Admiral Nelson and Admiral Mahan, male-male and Man2Man, expressed in a martial and manly context, would have been normal and natural --

as it should for us today.

And in that regard, I'm grateful to both Mr Haley and Mr Theroux for bringing to our attention Jack London's very felicitous turns of phrase about a "great Man-Comrade" who should be "so much one with me that we could never misunderstand," adding: "He should love the flesh, as he should the spirit."

That's what every Man should hope for:

A great Man-Comrade who should be so much One with me that we would never misunderstand, and who would love the flesh, as he should the spirit.

And notice how London combines flesh and spirit there -- just as we do and just as Sokrates and Plato do.

That's what true Male-Male, true Man2Man, is about -- Flesh and Spirit --

and that's what we must all search for in our affectional lives.

Not meangingless hook-ups, but the Great Love of a Great and Heroic Man-Comrade.

Fantasy?

NO.

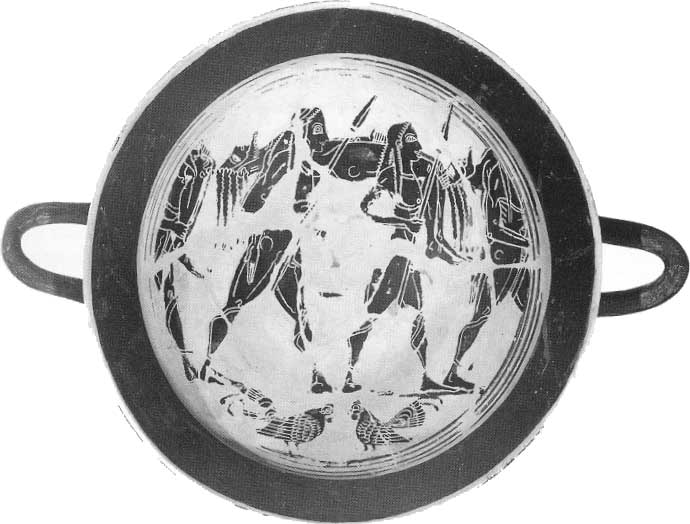

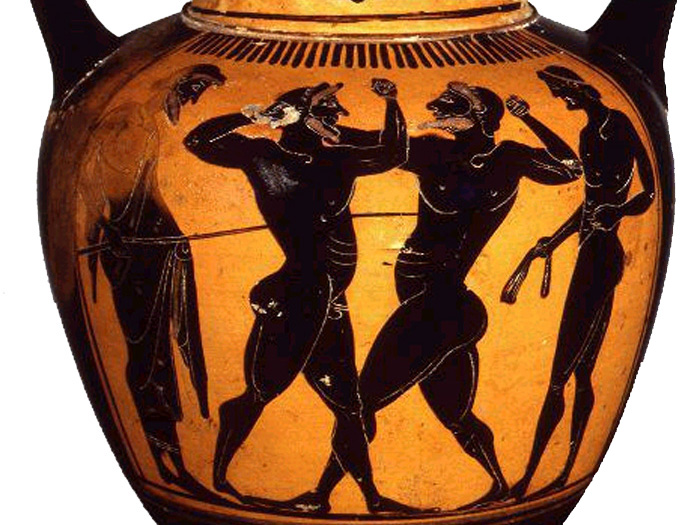

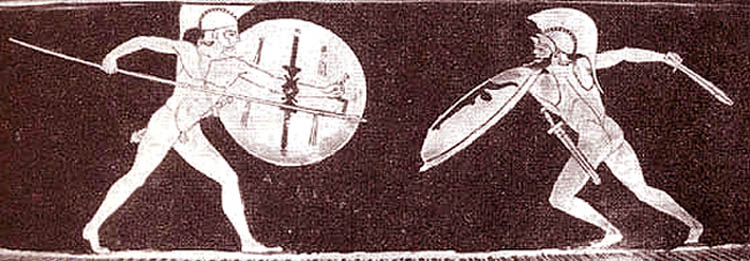

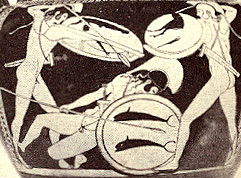

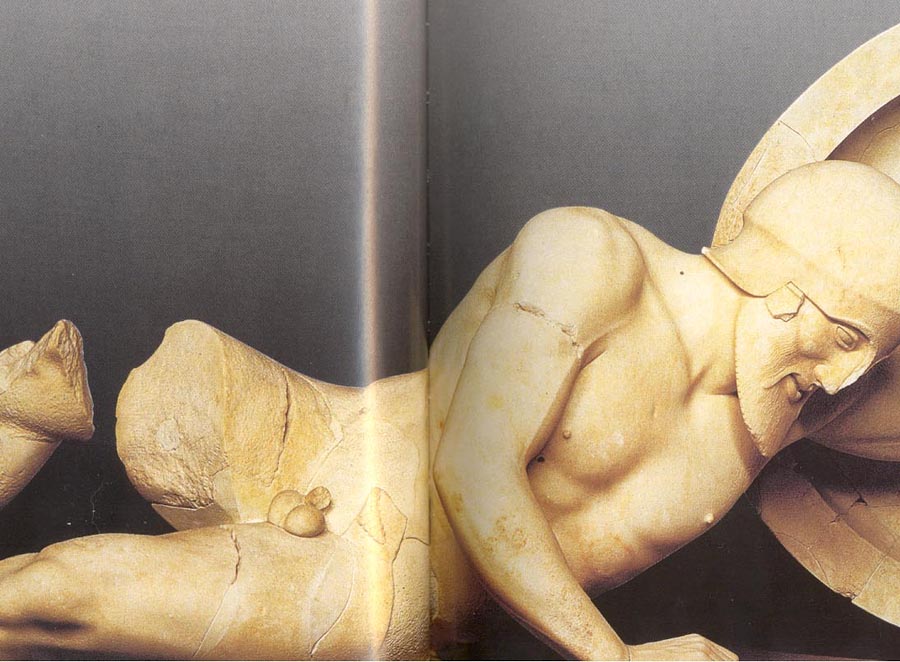

David and Jonathan, Harmodius and Aristogeiton, Alexander and Hephaestion, Nelson and Hardy, Mahan and Ashe --

and, let us hope, London and Sterling.

And those are just a few examples, drawn from among people who were famous for other things -- staving off the Philistines, killing tyrants, conquering the world, stopping the French, and revolutionizing naval warfare.

Among ordinary guys, and in the long history of this world, there have been without doubt not hundreds of thousands, but literally MILLIONS of Man-Comrades who loved the Flesh as they did the Spirit.

And you too can have such a Comrade, if you will not just work towards that goal --

but Fight for it.

And for him.

Again:

You can have such a Comrade, but you will have to FIGHT for him.

I thank Warrior Brian Hulme for yet another excellent post about the Love of Warriors.

Bill Weintraub

February 5, 2011

© All material Copyright 2011 by Bill Weintraub. All rights reserved.

Related article:

This aspect of our work is the one that's most disturbing and indeed frightening to our opponents:

That we combine the Love of Man with the Love of Fighting Spirit.

Which is Warrior Spirit.

The Warrior God is the Guardian of that Spirit.

You may call him Jesus Christ as Robert Loring does.

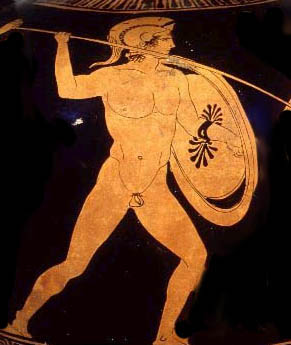

You may call him Ares as did the Greeks.

What's important is that you understand and acknowledge

the vital role He plays in Your Life.

and

who reject anal penetration, promiscuity, and effeminacy

among men who have sex with men

This aspect of our work is the one that's most disturbing and indeed frightening to our opponents:

That we combine the Love of Man with the Love of Fighting Spirit.

Which is Warrior Spirit.

The Warrior God is the Guardian of that Spirit.

You may call him Jesus Christ as Robert Loring does.

You may call him Ares as did the Greeks.

What's important is that you understand and acknowledge

the vital role He plays in Your Life.

AND

Warriors Speak is presented by The Man2Man Alliance, an organization of men into Frot

To learn more about Frot, ck out What's Hot About Frot

Or visit our FAQs page.

| Warriors Speak | Ask Sensei Patrick | Warrior Fiction | Frot: The Next Sexual Revolution | Sex Between Men: An Activity, Not A Condition |

| Heroes Site Guide | Toward a New Concept of M2M | What Sex Is |In Search of an Heroic Friend | Masculinity and Spirit |

| Jocks and Cocks | Gilgamesh | The Greeks | Hoplites! | The Warrior Bond | Nude Combat | Phallic, Masculine, Heroic | Reading |

| Heroic Homosex Home | Cockrub Warriors Home | Heroes Home | Story of Bill and Brett Home | Frot Club Home |

| Definitions | FAQs | Join Us | Contact Us | Tell Your Story |

© All material on this site Copyright 2001 - 2011 by Bill Weintraub. All rights reserved.

This aspect of our work is the one that's most disturbing and indeed frightening to our opponents:

That we combine the Love of Man with the Love of Fighting Spirit.

Which is Warrior Spirit.

The Warrior God is the Guardian of that Spirit.

You may call him Jesus Christ as Robert Loring does.

You may call him Ares as did the Greeks.

What's important is that you understand and acknowledge

the vital role He plays in Your Life.

The masculinity of men flows from their group. Their natural masculinity combines and gets manifold when masculine men unite. The camaraderie, mutual understanding, support, learning the ways of the world as a male, fighting together, dealing with roughs and toughs of life together -- they all help to develop the natural masculinity that exists within them.

They had many words for struggle and combat and fighting and strife -- maches, eris, hamilla, agon, polemos, ares -- and athlos, the word from which we derive our word "athlete."

In Greece, athletai could be rivals on the playing field or the battlefield.

Warrior Kosmos:

Manly Aggression, Manly Virtue:

Which would you rather be?

Some dork in a rubber mask?

Or a Warrior?

You're gonna die anyway.

And your money will die with you.

Admiral Mahan, Naval Critic, Dies

Special to THE NEW YORK TIMES

WASHINGTON, D. C., Dec. 1--Rear Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan, U. S. N., retired, America's foremost naval strategist and the world's greatest authority on sea power, died suddenly at the United States Naval Hospital here at 7:15 o'clock this morning of heart disease.

Three intimate friends of Admiral Mahan, who met him frequently on his visit to Washington this Winter, expressed the belief tonight that the war in Europe had hastened his death. They said that Admiral Mahan was not only most keenly interested in the great struggle, its relation to sea power, and the naval and strategic problems and lessons being solved or taught by the war, but that the events of the war greatly excited his mind and heart.

Admiral Mahan came to Washington on Nov. 1 to take up his labors as a research associate in the Department of Historical Research in the Carnegie Institution, and was pursuing a special line of historical research with a view to writing a history of American expansion and its bearing on sea power. This was to be a monumental work, and he had given thought to it for many years. But he had hardly made a beginning when his heart gave way, overtaxed by his keen interest in the European war.

Hostilities Affected Him

Though he was in his seventy-fourth year, Admiral Mahan was in apparently good health until the war began. The first month of hostilities deeply affected him. There were great demands made upon him for comments as a naval expert, and during the early days of the war he gave many interviews and wrote a number of articles dealing with the contest. The demand on him from American and foreign publications was cut short by President Wilson's order prohibiting American military and naval officers from commenting on the conflict, but Admiral Mahan, while discontinuing his writings on the war, never lost interest in it one moment. Signs of organic heart disease developed in September, and recurred late in October, just before Admiral Mahan came to Washington with Mrs. Mahan and their daughters, Helen and Ellen.

Only last week Admiral Mahan visited Secretary Daniels at the Navy Department, and Mr. Daniels said tonight the Admiral was the best-informed man on the war and its lessons he had conversed with. On Saturday the Admiral's condition became such that he decided to enter the naval hospital here. He died in the presence of his wife and two daughters. His son, Lyle Mahan, a New York lawyer, came to Washington tonight.

Admiral Mahan was as familiar with Europe, her history, and armaments as he was with American history, and knew many of the men actively identified with the war in high places in England, Germany, and France. Some of his intimate friends among the military and naval men in Europe had lost their lives in the war and this shocked him. Some of these officers he met in his travels, and when he received honorary degrees at Oxford and Cambridge and many more when he went to The Hague in 1899 as American Naval delegate to the First Peace Conference.

There were distinct reasons why the American people congratulated themselves upon the presence of Admiral Mahan, then Capt. Mahan, in the First Hague Conference. He was not only a naval strategist and scholar, but was even then regarded as the most eminent living expert in naval strategy. Then he had always consistently advocated strong navies and preparedness for war with special reference to naval influence in making for peace. Added to his equipment as a diplomatist in the delicate and complex task before The Hague Conference was his experience as a public man who had been hailed as the first great exponent of the philosophy of sea power.

Book Made Him Famous

His great reputation had been developed in the nine years immediately preceding the First Hague Conference. It was in 1890 that his first book of international importance, "The Influence of Sea Power Upon History," was published in Boston and made the author known around the world. This book is really responsible for the German Navy as it exists today. When it was published it was immediately translated into German. Emperor William was so impressed with the book that he ordered a copy placed in the library of every German warship, and ordered all German naval officers to read and study it. Emperor William praised it as the greatest modern work on naval affairs, and the greatest work on sea power. This book taught the Germans the importance of gaining sea power.

Admiral Mahan himself had told how it was that he came into the greater work--how, when reading Mommsen in the English Club at Lima, he was struck with that historian's failure to recognize the all-important influence of sea power on Hannibal's history. He wrote out the whole outline of "The Influence of Sea Power," discussed it with Admiral Luce, and then set to work with painstaking method. He chose the term "sea power" with the deliberate purpose of challenging attention. He is the coiner of that term in its present significance.

"Purists, I said to myself," he remarked, "may criticize me for marrying a Teutonic word to one of Latin origin, but I deliberately discarded the adjective 'maritime' being too smooth to arrest men's attention. I do not know how far this is usually the case with phrases that obtain currency. My impression is that the originator is himself generally surprised at their taking hold. I was not surprised in that sense. The effect produced was that which I fully proposed, but I was surprised at the extent of my success. 'Sea Power,' in English at least, seems to have come to stay, in the sense I used it. The 'sea powers' were often spoken of before, but in an entirely different manner--not to express, as I meant to, at once an abstract conception and a concrete fact."

Retired After Forty Years' Service

Admiral Mahan was born at West Point, N. Y., Sept. 27, 1840. His father was D. H. Mahan, an eminent Professor of Engineering at the United States Military Academy. On Nov. 17, 1896, Admiral Mahan was retired on his own application, after forty years' naval service, in order to be able to devote himself to his writings on sea power. Once since then he has been called to active duty--in May, 1898, when he was appointed a member of the Naval War Board, commonly known as the Strategy Board, during the war with Spain.

Admiral Mahan was a man of most interesting and admirable personal traits. Slender and erect, he was about 6 feet 2 inches tall, with finely chiseled features, very blue eyes, and a closely-cropped Vandyke beard. He was soft and gentle in voice and had a pleasant but reserved manner, perhaps a little cold to those who did not know him well. He was a man of high religious ideals. Sunday week, while attending service at St. Thomas's Church, he sang all the hymns and chants in the Episcopal service.

A naval officer said that the chapters of Admiral Mahan's great work on "The Influence of Sea Power Upon History" were first read as lectures to officers at the Naval War College at Newport and were then published. Two years later appeared his "Influence of Sea Power on the French Revolution and Empire," in the Spring of 1897 his "Life of Nelson, the Embodiment of the Sea Power of Great Britain," and in the following Winter his "Interest of America in Sea Power, Past and Future." Just after his life of Nelson appeared Harold Frederic cabled to The New York Times from London that the reviewers of the London dailies sat up all night with the advance copies to rush long reviews into print the next morning.

Navy Department's Tribute

The Navy Department tonight issued this tribute to Admiral Mahan:

"Admiral Mahan became famous as an author and historian in the early nineties, when his books on 'The Influence of Sea Power Upon History' and 'The Influence of Sea Power Upon the French Revolution' were published. These were followed by a 'Life of Nelson.' These books were classics in their line, and were widely read throughout the world. In England and Germany in particular they received the highest commendation, and in every country possessing a navy they became veritable text books in naval strategy. In England the leading naval men of the day confessed that it had remained for him to elucidate the work of the British navy in a way that they themselves had never understood or even dreamed of.

"Since his first books he has written many of lesser importance, and these and his essays have kept him before the world as the greatest modern writer on naval strategy. He was a close student of world politics, and his writings on the trend of the politics of the leading nations of the world were accepted as an authority. It may be safely said that no writer of modern times evinced a keener insight in the affairs of the world or expressed himself concerning them more clearly and convincingly than did the late Admiral Mahan.

"His death will cause international regret not only because of the high esteem in which he is held in every country of the world interested in naval affairs, but also because of the fact that his death leaves a void among naval and political authorities of the world that no author and writer can fill."

At the express request of Admiral Mahan there will be no naval funeral. Simple services will be held at 9 o'clock tomorrow night at St. Thomas's Church. The body will be then taken to the Mahan home at Quogue, L. I., for private interment.